By Leslie Lindsay

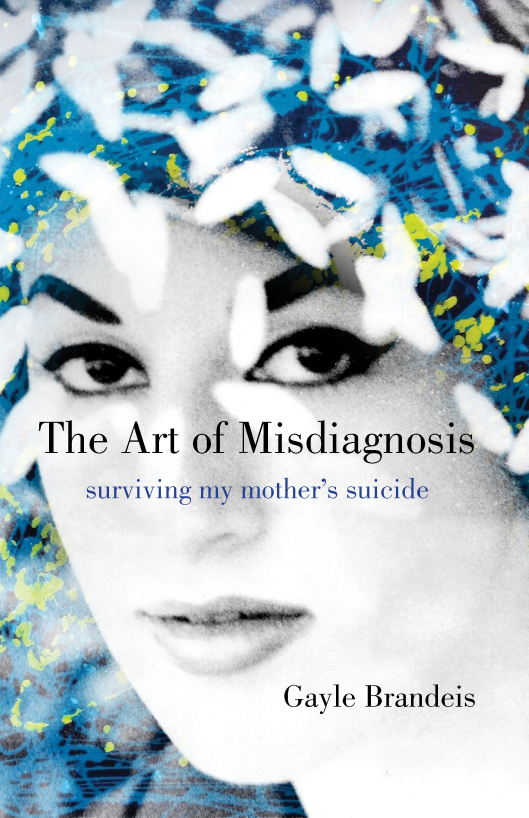

Razor-sharp, raw, poetic memoir about mothers and daughters, suicide, mental illness, and grief.

Gayle Brandeis’s mother disappeared shortly after Gayle gave birth to her youngest child, Asher. Several days later, her body was found hanging in the utility closet of parking garage of an apartment building for the elderly.

THE ART OF MISDIAGNOSIS is a gorgeous read about a less-glamorous time. Gayle is struggling with grief and heartache, as well as the soupy surreal time of postpartum. Gayle takes this dichotomy of death and birth and weaves it into a coherent, poetic narrative that brings readers into the grief experience.

What’s more is the family history surrounding a series of bizarre medical symptoms that often masked themselves as psychoses. Or was it psychosis, after all? It’s hard to say because the symptoms tend to overlap: delusions, paranoia, factitious disordersfactitious disorders; Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, porphyria. For the last few years of Gayle’s mother’s life, she was working on a documentary about these

disorders, called THE ART OF MISDIAGNOSIS. Gayle takes that script and braids it, along with her own feelings and experiences into the narrative.

Be sure to watch the stunning book trailer here:

I found the writing clear and glittery, the medical mystery fascinating, but most of all–I wondered, what really happened?

From the back cover:

“Written by a gifted stylist, THE ART OF MISDIAGNOSIS delves into the tangled mysteries of the disease, mental illness, and suicide, and comes out the other side with grace.”

I am so, so honored to welcome Gayle to the blog couch.

Leslie Lindsay: Gayle, I find your story so important and so honest and I thank you for sharing it with us. Like you, I had a tumultuous relationship with my mother. Like you, I lost her to suicide a little over two years ago. I don’t have to ask what was haunting you when you set out to write THE ART OF MISDIAGNOSIS; I know. But I am curious about what kept you going with the writing?

Gayle Brandeis: Thank you so much, Leslie—I’m so grateful for your kind words and so happy to appear on your blog. I’m sorry that you are part of this suicide loss survivor club, too—it’s not a community I’d wish on anyone, but I very much appreciate connecting with other survivors. Our stories are so often kept in the shadows, and I think when we share this complicated form of grief, we can help reduce stigma, help release shame. That was part of what drove me, but what drove me on a more personal level was the compulsion to dig and dig and dig until I could come to some place of understanding—or, if not understanding, at least a place of greater peace—with my mom, her life as well as her death. I wanted to make some kind of sense out of the chaos.

L.L.: While THE ART OF MISDIAGNOSIS is as much about death as it is birth. Your youngest son, Asher was born just a week before your mother took her life. You share several beautiful passages in the narrative about Asher/Ashes/Ash/er/es […] it’s very poignant and also a nod to grief; I think we often grasp at small connections as our mind absorbs loss. We want to make sense of the tragedy. You also share a really strong image of your sister carrying your mother’s ashes in one hand and Asher in his car seat in another arm. Can you talk about the juxtaposition of life and death?

Gayle Brandeis: Life and death are always around us, of course—cue “The Circle of Life” music!—but losing my mom a week after giving birth drove that home in such an intense way. That moment where my sister was walking down the hall holding my baby Asher at the same times he was holding our mom’s ashes, embodies that juxtaposition so perfectly for me, the beginning and end of life in her hands (and realizing those two words—Asher, Ashes—are just one letter apart; just one breath apart, as I write in the book). Having a new baby kept me from running off the rails, I think—I’m so grateful he brought his ray of light to ground us and bring joy through that painful time. I’m very glad I took notes as it was all happening because both grief and giving birth can give one a kind of amnesia—some part of me must have known that, and took notes to guard against this double whammy. Those notes helped greatly once I was ready to write this story—they brought me right back to the intensity of the experience, of holding the reverberations of grief and birth in my body all at once.

L.L.: Shifting gears a bit to the medical side of THE ART OF MISDIAGNOSIS…your mother believed she (and your family) suffered from a couple of rare medical syndromes: Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and also porphyria. Later, there’s mention of factitious disorder and malingering syndrome. You had me Googling all kinds of things! Can you break down what you understand about these illnesses, please?

Gayle Brandeis: I feel like I still don’t understand as much about Ehlers-Dalos syndrome and porphryria as my mom had wanted me to. Both are genetic disorders; Ehlers-Danlos is a connective tissue disorder which has a several manifestations—the most common seem to be the hyper mobility type, in which joints are extra loose, and the vascular type, which affects blood vessels (as well as other parts of the body) and can lead to issues like rupture of the aorta (my mom felt certain that this type ran in the family). Just in the last couple of years, several people I know have been diagnosed with EDS, or a family member has, or it’s been suspected by doctors, so it’s possible that my mom was right when she believed it’s not a rare disease, just rarely diagnosed. Porphyria is a metabolic disorder that has all sorts of physical and mental presentations, including some pretty wild ones, like a thirst for blood and “werewolfism”; it may be what drove King George “mad” (and thus helped America become America.) There is something kind of mythic about it, although of course it leads to very real suffering. As I mention in the book, I was kind of disappointed when it turned out I didn’t have porphyria, after all—if I had to be chronically ill (and of course I would rather not be!), that was an interesting illness to be associated with.

Factitious disorders were a more recent discovery for me. In the book, as you know, I talk about how I prolonged my illness for a year after it went into remission when I was a teenager because I didn’t know how not to be “the sick girl”—it had become my identity. A few years ago, a friend mentioned the word “malingering” and I knew I had heard it but didn’t fully understand what it meant; when I looked it up and discovered that it meant gaining some sort of reward from pretending to be ill, I thought, well, that’s what I was doing as a teenager. I later learned, though, that those who malinger get some sort of material benefit from their charade—money, etc.—but those with factitious disorders get their reward directly from the experience of being ill and the attention it inspires. That struck home all the more. The most serious form of this is Munchausen syndrome (named for Baron von Munchausen, a character who made up outlandish tales); there’s also Munchausen by proxy, in which a person, often a mother, will make someone else, often their child, ill through a variety of means. My mom didn’t have Munchausen by proxy, but our relationship as “the sick girl” and “the mother of the sick girl” was definitely an unhealthy and co-dependent one.

L.L.: And yet, and yet…at times your mother seemed to suffer from some kind of mental illness. As I read, several diagnoses came to mind: schizoaffective disorder, bipolar, narcissism. What do you think was really going on?

Gayle Brandeis: It is still wild and ironic to me that I went out of my way to appear ill when I wasn’t and she refused to acknowledge she had mental illness when she did. After doing my own research and interviewing psychiatrists, it seems likely that she had a paranoid delusional disorder, which is different from schizophrenia and is apparently incredibly hard to treat. Even if she had ever been properly diagnosed, it’s unlikely there would have been a medication or other therapy that could have significantly helped. Learning this was a relief in a way—I had been beating myself up, wondering what I could have done differently, how I could have helped her more, and when a psychiatrist I interviewed said there really isn’t anything I could have done, it helped me let go of some of the guilt I had been carrying. I do think she had narcissistic personality disorder, as well—the world very much revolved around her.

L.L.: THE ART OF MISDIAGNOSIS teeters between time periods and also is told, in part, by letters you wrote to your mother after her death at the urging of your therapist. There are a million ways you could have structured this narrative. How is that you decided on this structure?

Gayle Brandeis: The structure evolved as I worked on the book. The letter my therapist suggested I write to my mom was something I truly had started writing for myself alone, and as I delved into my history with my mom, at some point I realized that this letter could provide a deeper context for our relationship in the book, since the present tense narration around her suicide was urgent and immediate and didn’t really allow for that kind of reflection. The film transcription came in a bit later in the process—I had decided to borrow my mom’s title but I hadn’t considered using the film itself in the memoir, mostly because I hadn’t been ready to watch it after her death. Once I did let myself view it, I realized that braiding the film into the book could give my mom a chance to speak for herself on the page. And the research elements came in naturally, too—they were part of my investigation and it made sense to weave them in. It seems fitting that the story ended up being told in a complicated, fragmented way—it mirrors how complicated grief after suicide can be (but it also allowed me to create form out of chaos in a very satisfying way.)

L.L.: There are other memoirs about mental illness and suicide; mothers and daughters, but this one is illuminating and uplifting in some regards; redeeming in others. What do you think sets THE ART OF MISDIAGNOSIS apart? What do you hope readers take away? And did it transform you in writing it?

Gayle Brandeis: Of course every story of suicide is unique because of the voice and vision of the person writing, but there are also important points of connection between our stories. I take a dance class called “Groove” where the guiding principle

is “unified but unique”—you are given a few simple movements to do with each song that are touchstones for everyone in the class, but then you make the movements your own, layer on your own quirky stuff. I think of my book that way—I hope people who have gone through similar experiences will find a sense of solidarity and community, that it will help them feel less alone, but I also hope that this book will offer something new—a fresh approach to form, a singular experience told through my very particular (and sometimes peculiar, as was said in a review, which I love) body and mind. I very much hope readers leave the book with a sense of hope (and perhaps some inspiration to tell their own stories.)

Writing this book transformed me more than I could ever say. I was asked to do a self-interview for The Nervous Breakdown, and I ended up asking myself “How did writing this book change you?” eleven times, with eleven different answers, and I could have kept going. I am a different person than I was when I began writing the book—a stronger person, a braver person, a more open person. I am so deeply grateful for the journey of this book.

L.L.: Gayle, it’s been such a pleasure. Thank you! Is there anything I forgot to ask that I should have? Like, maybe what’s on your end-of-the-year-bucket list, what are you reading, what your guilty pleasures are, or how Asher is doing?

Gayle Brandeis: Thank you so much for having me—this has been a treat! I don’t think you forgot anything at all, but I’m happy to answer these questions! Not sure I have an end-of-the year bucket list, but I do want to see the Northern Lights before I

die. Speaking of death, I’m reading a book that comes out next year, I AM, I AM, I AM: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell, which is a beautiful exploration of how awareness of death can help us appreciate life all the more deeply. As for guilty pleasures, hmmm…I gobbled down Stranger Things 2, but I don’t feel guilty about that at all! Hot baths are perhaps my guiltiest pleasure—guilty because I don’t like to waste water, but I sure do love a good, long, hot soak. And Asher’s doing great! It’s kind of amazing to me that he’s 8 now—he is such a barometer of how long I’ve lived without my mom. He’s just about as tall as my armpits these days. Time is so weird. Thanks for asking about my sweet boy (and thanks for all of your other great questions—so very grateful!)

- Instagram: @gaylebrandeis

- Twitter: @gaylebrandeis

- Website

- Amazon

- Barnes & Noble

- BAM

- IndieBound

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Gayle Brandeis is the author, most recently, of the memoir The Art of Misdiagnosis: Surviving My Mother’s Suicide (Beacon Press) and the poetry collection The Selfless Bliss of the Body (Finishing Line Books). Her other books include Fruitflesh: Seeds of Inspiration for Women Who Write (HarperOne), and the novels The Book of Dead Birds (HarperCollins), which won the Bellwether Prize for Fiction of Social Engagement, Self Storage (Ballantine), Delta Girls (Ballantine), and My Life with the Lincolns (Henry Holt), which received a Silver Nautilus Book Award and was chosen as a state-wide read in Wisconsin. Her poetry, essays, and short fiction have been widely published and have received numerous honors, including a Barbara Mandigo Kelly Peace Poetry Award and a Notable Essay in Best American Essays 2016. She currently teaches at Sierra Nevada College and the low residency MFA program at Antioch University, Los Angeles.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Gayle Brandeis is the author, most recently, of the memoir The Art of Misdiagnosis: Surviving My Mother’s Suicide (Beacon Press) and the poetry collection The Selfless Bliss of the Body (Finishing Line Books). Her other books include Fruitflesh: Seeds of Inspiration for Women Who Write (HarperOne), and the novels The Book of Dead Birds (HarperCollins), which won the Bellwether Prize for Fiction of Social Engagement, Self Storage (Ballantine), Delta Girls (Ballantine), and My Life with the Lincolns (Henry Holt), which received a Silver Nautilus Book Award and was chosen as a state-wide read in Wisconsin. Her poetry, essays, and short fiction have been widely published and have received numerous honors, including a Barbara Mandigo Kelly Peace Poetry Award and a Notable Essay in Best American Essays 2016. She currently teaches at Sierra Nevada College and the low residency MFA program at Antioch University, Los Angeles.

- GoodReads

- Facebook: LeslieLindsayWriter

- Twitter: @LeslieLindsay1

- Email: leslie_lindsay@hotmail.com

- Amazon

[Cover and author image courtesy of Beacon Press and used with permission. Aurora Borealis/Northern Lights image retrieved from USAToday.com, quirky carpet layers from , the world revolves around me from, Life & Death Tree from Pinterest, no source noted, reading/book image from L. Lindsay’s personal archives, all on 11.16.17]

Share this: