an Unnecessary woman will always sit in the back of my head, beneath louder recollections of other books that I have loved and loved again. The book came to me in a moment of violence.

After 120 pages of imagining Rabih Alameddine — seventy-two-year-old woman, sitting at a grand desk, writing about a remote character, I suddenly have to ask myself how a man can write this book. Rabih Alameddine, fifty-eight-year-old man, has thoughtlessly brought down walls of certainty that I had built for myself. I’m taken back to a moment in which I had carelessly declared that we must keep men out of the worlds built for us by women writers. I sat comfortably in Ferrante’s Italy and Adichie’s Nigeria and strengthened my belief that books about women cannot be written by men. I’m yet to decide if I was wrong.

In Alameddine’s Beirut, I recognized a familiar discomfort. The same discomfort that lies just outside your comfort zone, the same discomfort that makes you re-watch Friends instead of finally starting Game of Thrones.

an Unnecessary woman is about seventy-two-year-old Aaliya who is ‘godless’, ‘childless’, ‘fatherless’. An unassuming boy from my newly formed MA class snatched the book from my hands while I was on page twenty-three and read the blurb at the back of the book. “Fatherless? How can someone be fatherless? Jesus paida hui thi kya?”

That moment ended there, and even before I could ask myself why Aaliya was fatherless, the boy in my class had answered his own question. Seventy-two-year-old Aaliya is a divorcee, living in a post-war Beirut. At different points in the book, she almost describes herself as lonely. Her blood relatives never became her family, and we never find out their names. Her relationship with her mother is stained with the darkest shade of violence that softens only in the latter half of the book, in a rather intense moment that doesn’t seem to end. Her impotent ex-husband remained only a speck in her life, and the only thing she learnt from being married to him was how to sew on buttons on to cloth.

We invade into Aaliya’s life for the first time during a sharp moment. She says,

You could say I was thinking of other things when I shampooed my hair blue, and two glasses of red wine didn’t help my concentration.

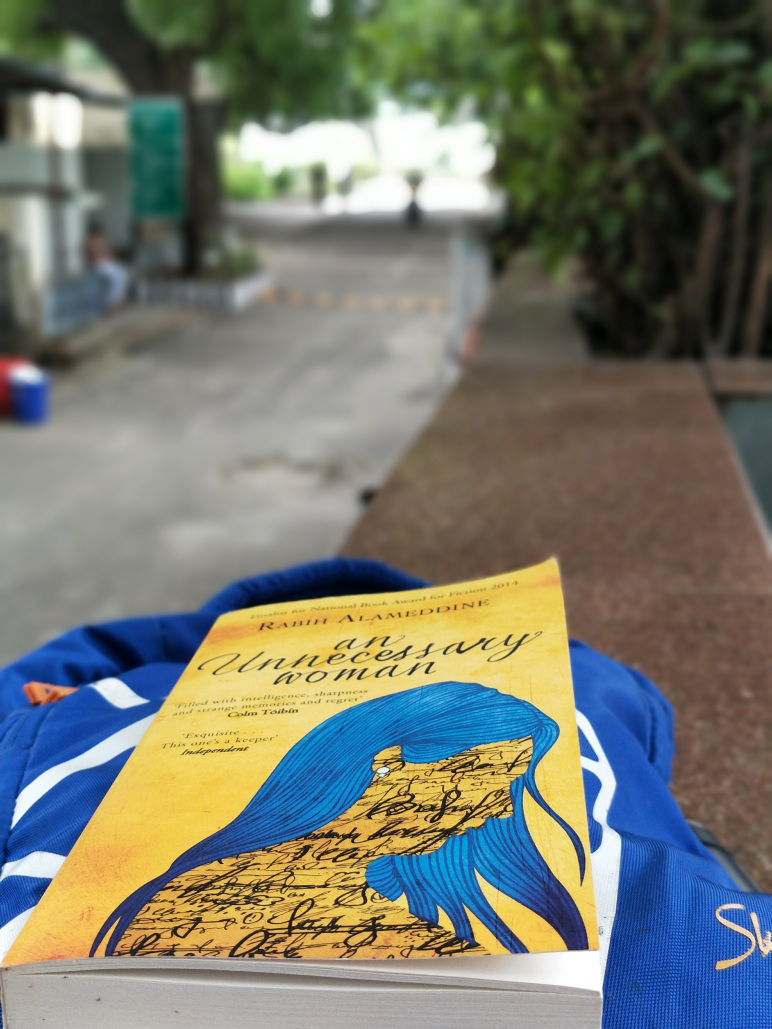

Perhaps it also helped that just before I picked up the book, I had coloured my hair blue. Like in the case of my reality, it is easy to forget that our protagonist’s hair is blue. We’re reminded of this because of the bright yellow cover of the book, in the center of which is the silhouette of a woman with blue hair.

In the AUD campus

When I think of women writers, I visualize kind figures with hazy faces who convince me — with their magic writerly powers — to want to become the characters they’ve created. With Alameddine, I visualized (in the beginning, at least), the figure of a woman who pushed me into the mind of a character I wasn’t ready to become. Not because Aaliya is lonely, but because she possesses a knowledge that everyone I know will be envious of. This knowledge is visible through the innumerable references to writers, philosophers, and poets. She refers to them, and their work in simple situations, as if they weren’t really great writers, philosophers, and poets but were her closest friends.

Her relationships with people are irrelevant motes of dust in her life, instead she cherishes spaces with a passion I’m now accustomed to. While walking home one day, she says,

No matter where I’ve been or how long I’ve been away, my soul begins to tingle whenever I approach my apartment. The sharp turn that leads to my street, the brown-and-gray building that I call “the new one” even though it was built in the early seventies and is certainly no longer new, are signs that announce I am close. The pleasurable sensation of almost arriving and the impatience of not yet being there begin at those markers. My first act upon entering the apartment, after shutting the door behind me, is simply to drop on my sofa and rest. My home.

Perhaps if one day, I find that the tips of my fingers (or soul) tingle while I’m on the way home after a long day, I will know that I’ve made it, that I’m finally brave enough like Aaliya is.

—

The first moment of surprise in the book seeped in just as quickly as I reached page three. We learn that on the first day of the first month of every year, Aaliya begins translating a book. She translates into Arabic — from French, or English, depending on the book. Some translations take more than a year to complete, some take just a year. In another moment in the book, while she is picking the next book she wants to translate, she wonders if she should pick a 1000-page book, because she has just finished translating another 1000-page book. She never wonders whether she is up for the task, she only wonders if she needs a change.

These manuscripts — all thirty-seven of them, completed over fifty years — have never been published. They lie in crates in the maid’s room in her apartment, piled up like inconsequential entrance exam textbooks that have never been used.

She recounts translating all books with a surprising clarity. I asked myself, several times, whether I remembered working on pieces like she remembers working on translations. Her knowledge of languages, of books, of theories makes me feel inadequate in a very real way, and yet I never feel the need to hide because Aaliya is the one hiding. She’s hiding everything she knows in crates in the maid’s room of her apartment.

By the end of the book, we’re well acquainted with maybe seven characters, but amongst these, Aaliya’s apartment stands out the most. This is an apartment that remains hers by a stroke of luck. Aaliya’s landlord and neighbour let her keep the house after Aaliya’s husband left her. And while Aaliya’s family hounded and pounded on the frail door to her apartment several times, she never let go of the place. At one point in the book, Aaliya says,

Let me just mention here that just because I slept with an AK-47 in place of a husband during the war does not make me insane.

It probably didn’t help that her half-brothers were indignant that a single old woman chose to live in a large house all by herself when she had brothers who needed it more.

—

My mother says that whenever you go for a satsang[1], the topic of the day is always uncannily relevant to whatever’s happening your life. I wouldn’t know because I’ve never been to a satsang, but I’m having small doubtful moments that tell me that some books are also uncannily relevant to whatever’s happening in your life. Aaliya’s aloneness was like a kind slap in the face after having hordes of people promise me that moving to a different city and living alone is the worst thing I will do to myself. Perhaps they’re right. But maybe not.

Aaliya lives in a bubble of loneliness that she’s able to survive because of her translations. Her system keeps her going, and her work becomes her faith. I only wish that Alameddine had come to me before I based my move to Delhi on several assumptions that ended in the belief that living alone is a nightmare.

Aaliya’s desk at home tells me a different story, the tingling in her fingers on the way home tells me a different story and at this point I’m confused. She has championed living alone like no one else I know. And at the end, when Aaliya has suddenly remembered that she can alter her process of translation as she likes, her excitement on figuring out new ways to translate becomes mine, and her shallow breathing and increased heart beat rate is mirrored in my own. I’m excited, not just because I can imagine how much fun Aaliya will have, but because I know things I hadn’t thought of before.

It’s almost impossible to make a list of all the things that Alameddine has told me through Aaliya. He has given me innocent relationships between simple women, he has shown me a family that never was, he has shown me that people can be irrelevant, but most importantly, he has shown me what it is like to have spaces that you’re in love with — wholly, irrationally.

At the end of the book, I’m transported back to my MA interview. I declared very proudly, “I gravitate towards women writing. It’s not a conscious effort.”

Rabih Alameddine has confused me, but he’s also taught me that I don’t need an answer. So for now, I will believe that Aaliya is just one in a million, that Alameddine knew Aaliya. That perhaps in another world, he was Aaliya.

[1] Satsang – spiritiual discourse, google says.

Advertisements Share this: