The “revelations” this past week over Harvey Weinstein’s repeated assaults on women brought up some very troubling conversations about women. Many of the news reports showed Weinstein with various actresses who have accused him of sexual assault; the actresses were often smiling and near enough to Weinstein for him to have his arm around them. But as anyone who has ever been sexually assaulted by someone more powerful than them knows, smiling doesn’t mean you’re happy. It means you are being someone else, trying to survive. An article in the Independent this week (http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/harvey-weinstein-sexual-harassment-mental-health-women-suffering-anxiety-a7996511.html) suggests that most women, once they hit puberty, have to learn psychological coping skills to deal with the gaze of powerful men—and even then may be labelled as anxious or depressed. The reaction to the hashtag #MeToo (tweeted over half a million times as of Monday, according to CNN, http://www.cnn.com/2017/10/15/entertainment/me-too-twitter-alyssa-milano/index.html) shows that sexual assault—for men as well as for women—is all too prevalent in our society, and yet those assaulted feel so alone and so threatened that it is hard to speak up about it. For many of us (yes, #MeToo), it is safer to smile if we want to survive. It is safer to be someone else.

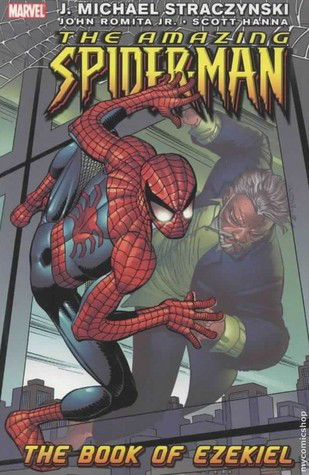

In Errol Lloyd’s Nini at Carnival, Nini gains power through the act of dressing up as an African queen.

This coping mechanism of being someone else has various translations in literature; in children’s books, it is often through the trope of dressing up. Dressing up can simply allow a character to try out a different persona and see if it fits; but it is interesting to look at how BAME characters in books “dress up,” especially female characters. Prior to puberty, dressing up is about becoming powerful. Two very different notions of power can be seen in comparing Errol Lloyd’s Nini at Carnival (Bodley Head, 1978) with Mary Hoffman’s Amazing Grace (Frances Lincoln, 1991). In Lloyd’s book, the titular character is part of a carnival parade, but she doesn’t have a costume. Her “fairy godmother” (really her friend dressed up in a fairy costume) comes along and gives her a piece of cloth in a pattern that could be intended as a Kente cloth (the royal cloth of the Akan people in Africa), wrapping it around her like an African ceremonial dress and saying that Nini is now “pretty enough to be Queen of the Carnival” (n.p.) which Nini, in fact, then becomes. In Hoffman’s story, on the other hand, Grace likes to dress up as story characters; “she always gave herself the most exciting part” (n.p.) according to Hoffman—which in most cases, happens to be the male part. Lloyd invests power for his Black female character in the historical traditions of African civilizations; Hoffman invests it in male characters, and often those male characters as written by white male “classic” authors such as Kipling, Longfellow, and of course J. M. Barrie. Guess which one of these two books has never been out of print since publication? No wonder World Book Day costumes are fraught for BAME Britons.

Grace in Mary Hoffman’s book feels powerful when she acts out stories of white and/or male heroes. Illustrations by Caroline Binch.

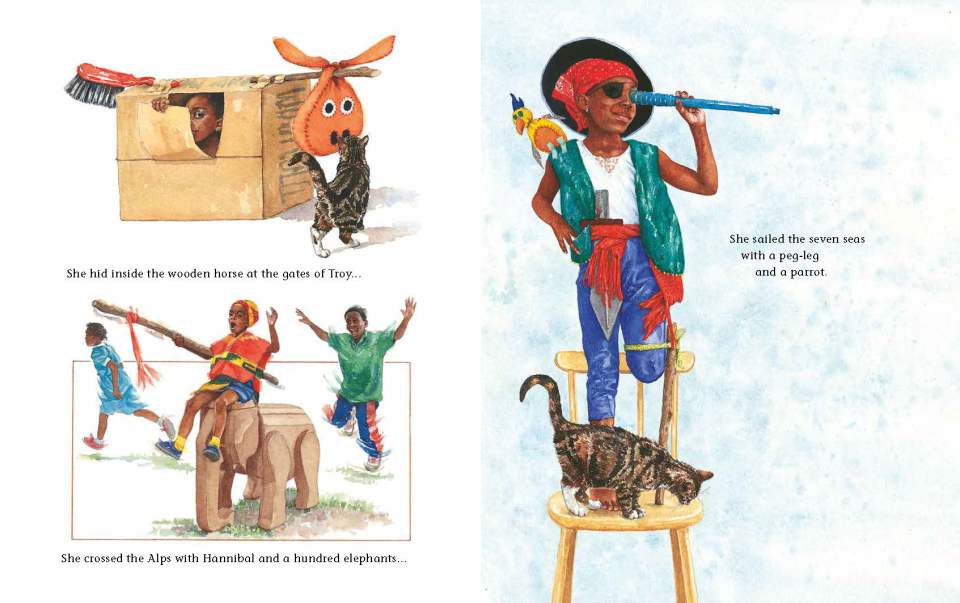

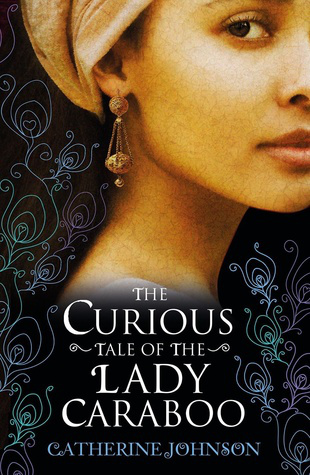

In YA books, dressing up changes from a focus on power to a focus on survival, particularly for BAME young women. Two different approaches to dressing up can be seen in Tanya Landman’s Passing for White (Barrington Stoke, 2017) and Catherine Johnson’s The Curious Tale of the Lady Caraboo (Corgi, 2015). In both books, the main female protagonist must escape those who have the power to destroy her happiness and security by becoming someone else. Rosa, in Landman’s book, is light enough to “pass for white” because she is the daughter of her slave master. Her master wants to keep Rosa enslaved, and destroy her family life and chances for happiness. And as Rosa and Benjamin, another slave with whom she falls in love, knows, “White folks can do whatever the hell they pleased . . . And then they’d say it was your own damned fault” (3). So Rosa dresses up in the most powerful costume she can think of: that of a rich, elderly, white man, with Benjamin as her slave, in order to escape to freedom. A colleague who teaches slave narratives said that students often argue that passing for white is being a “traitor to your race”—but such attitudes are similar to those who say that women who accept contracts in Hollywood after being assaulted were “trading on sex”. Survival in the face of overwhelmingly powerful enemies sometimes depends on pretending to be like the powerful.

For BAME characters in YA novels, “dressing up” was not just fun and games.

Johnson’s book addresses sexual assault head-on, also in a historical novel, by opening her book with the main character’s rape. Mary Wilcox, alone and friendless, is raped by two farm boys even though she is dirty, weak, and “looked like a savage” (2). Mary knew that rape happened to women “acting the coquette and suffering the consequences” (1) but when she is raped that night, she understands that it is not about women “asking for it” but about men exerting power. And while she rejects that kind of power, she still knows that to survive, she would have to be somebody else: “an Amazon warrior woman who could turn on her attackers. Better still, a fighting princess, a beautiful girl with a dagger at her waist and a quiver of magical arrows. They would not dare touch her then” (4). Mary does not become a warrior, but she does become a princess from an exotic land, the Lady Caraboo, who speaks no English but reflects back “only what your people wanted me to be” (193)—the beautiful, the strange—to a white family who takes her in. In becoming someone else, she survives; but her disguise also allows her “to be something other than who I was; something fresh, something good, something capable of love and being loved” (194). This heartbreaking statement—that Mary thinks she has to be someone else to be loved—rings true for many women who think that their broken self will never be good enough to be worthy of love.

Becoming “what they want you to be” is another way to survive, as in Catherine Johnson’s novel. Cover photo by Bella Kotak.

Historical fiction is perhaps the easiest genre in which YA literature can represent the concept of becoming someone else for survival, but I want to end with one last example from fantastic fiction. Malorie Blackman’s Noughts and Crosses (Doubleday, 2001) concerns a world where the power positions between Black people and White people are reversed from contemporary society. But Blackman’s novel is less about race and more about power; both Crosses (Black people who hold most of the society’s power positions) and Noughts (White people who generally have to serve the Crosses) suffer from unequal power relations, but Noughts suffer far more. Callum, the Nought protagonist, has a sister named Lynette, who was “beaten and left for dead because she was dating a Cross” (124). Her way of coping with her powerlessness is through disguise: she tries to convince those around her that she is a Cross. As a blonde, White girl, her disguise is only self-deception. When forced to confront her despised whiteness, Lynette commits suicide, knowing she will never be able to cope with “a return to reality” (170).

From Ian Edginton and John Aggs’s graphic novel version of Noughts and Crosses–Lynette’s “madness” is her only chance at survival.

Everyone, at every age, practices “dressing up” to be a little bit different from our ordinary selves sometimes. But we need to be aware that dressing up can also be a way of hiding—or of surviving. Literature for children can remind us that sometimes it is safer to be someone else in societies where powerful people get away with crimes against the powerless.

Advertisements Share this: