The final part of my cities trilogy of posts sees me in Manchester, a place that has made worldwide news in recent times for the most tragic of reasons. I saw the floral tributes when I was there and it was deeply moving. Manchester is a great city with a rich history & I still think that even though it bucketed with rain the whole time I was there and I spent every moment on a spectrum of sogginess, never entirely dry. If any of you go to this fine place before 28 August I highly recommend Shirley Baker’s photographs at the Manchester Art Gallery; her images of Mancunians in the late 1960s-early 70s are absolutely wonderful.

Image from here

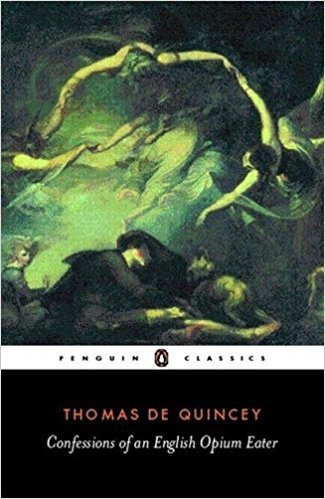

From the TBR mountain I’ve chosen two autobiographies, one from a writer born in Manchester, and one who has now made Manchester their home. Firstly, the classic Confessions of an English Opium Eater by Thomas de Quincey (1821). De Quincey was born in Manchester to a family of cloth merchants when Manchester was a major industrial centre for the cotton industry.

“On passing through Manchester, I was informed by several cotton manufacturers that their workpeople were rapidly getting into the practice of opium-eating; so much so, that on a Saturday afternoon the counters of druggists were strewed with pills…in preparation for the known demand of the evening. The immediate occasion of this practice was the lowness of wages, which at that time would not allow them to indulge in ale or spirits, and wages rising, it may be thought this practice would cease; but …I do not readily believe that any man having once tasted the divine luxuries of opium will afterwards descend into the gross and mortal enjoyments of alcohol.”

Yes, opium (laudanum) was legal and widely used at this time. DeQuincey suffers with excruciating stomach pains due to childhood poverty and starvation, and a well-meaning friend suggests he try opium to ease his what ails him:

“I took it – and in an hour – oh, heavens! What a revulsion! What an upheaving, from its lowest depths, of inner spirit! What an apocalypse of the world within me! That my pains had vanished was now a trifle in my eyes: this negative effect was swallowed up in the immensity of those positive effects which had opened before me – in the abyss of divine enjoyment thus suddenly revealed.” *

The record of positive experiences with opium meant Confessions was controversial on its release. But DeQuicey does not glamourise the drug nor his experience with it. After all, people wouldn’t get addicted to something which made them feel horrible, and DeQuincey is seeking to make people understand. He doesn’t shy away from all the effects of the drug, and his hallucinations under its influence are grim:

“I was kissed, with cancerous kisses, by crocodiles; and laid, confounded with all unutterable slimy things, amongst reeds and Nilotic mud.”

Overall, the feeling I was left with from this short biography was one of sadness. DeQuincey is ruled by something far more powerful than he is, and the sense is of a life half-lived, a life DeQuincey wishes had been different. He has a fatal flaw:

“I hanker too much after a state of happiness, both for myself and others; I cannot face misery, whether my own or not, with an eye of sufficient firmness”

And opium convinces him that this state is achievable. In so desperately wanting to believe this lie, DeQuincey is never able to shake free of his addiction. At the beginning of the novel he proclaims:

“I have at length accomplished what I never yet heard attributed to any other man – have untwisted, almost to its final links, the accursed chain which fettered me.”

But modern readers will know he never did accomplish this, and remained addicted his entire life. Confessions is very readable, much more so than other essays and similar of the period, and remains a thought-provoking insight into the nature of addiction.

Secondly, Red Dust Road by Jackie Kay (2010), a Scottish writer who has settled in Manchester and is the current Scots Makar. If Confessions left me feeling sad, Red Dust Road left me feeling warmed and moved, although it is not a comfort read. It is the story of Jackie Kay’s search for her birth parents, and like her other writing – poetry, fiction, short stories, children’s books – it is funny and affectionate and real and sad.

“the search is often disappointing because it is a false search. You cannot find yourself in two strangers who happen to share your genes. You are made already although you don’t properly know it, you are made from a mixture of myth and gene, you are part fable, part porridge. Finding a strange, nervous, Mormon mother and finding a crazed, ranting Born-Again father does not explain me. At least I hope not!”

That passage occurs near the start of the book, and so it is not a spoiler. We know Jackie finds her birth parents. What she does, expertly, is cut back and forth in time to show what has made her what she is. Raised in Glasgow by a white couple, Jackie and her (non-biological) brother are mixed race. Growing up in the 70s and 80s they encounter racism (there is a particularly chilling experience for teenage Jackie at Angel tube station). They also encounter a wonderful, unconditional love from their parents who are communists with a strong sense of right and wrong and a strong sense of fun. (Seriously, Helen and John Kay sound awesome.) While her brother has no interest in finding his biological parents, Jackie finds that falling pregnant with her own son spurs her on to trace her relatives. She discovers that her father was a Nigerian student who met her mother in Aberdeen when she was a nurse. Along the way, she has to pick apart the fairytales she has told herself about them since childhood, and the reality of who they are:

“they are ghosts one minute haunting the city of stone, and ordinary people the next. It is impossible to sustain them, or maintain them. I take another swig of gin. It is time to let them fend for themselves. It is time to let them go. They need to grow up, those young parents. They need to grow up because they are already old, and so am I.”

Red Dust Road is a hugely engaging memoir, full of warmth for all her family and written with humour without shying away from sadness. Ultimately it is a book about what makes us who we are, and how some of it is easy to pinpoint, some of it impossible to fully fathom. It is also about finding home, and how that can be in several places. Jackie Kay has a strong Scottish identity, lives in Manchester, and then visits Nigeria for the first time:

“The earth is so copper warm and beautiful and the green of the long elephant grasses so lushly green they make me want to weep. I feel such a strong sense of affinity with the colours and the landscape, a strong sense of recognition. There’s a feeling of liberation, and exhilaration, that at last, at last, at last I’m here.”

I highly recommend Red Dust Road. Jackie Kay has brought her poetic sensibility to write a glorious memoir about how ourselves, our families and our homes are always an unpredictable work in progress.

To end, a classic song by a classic Manchester band:

*Just say no, kids

Advertisements Share this: