(Here is my translation of a short story –or is it a kind of prose poem?– by the Italian author Dino Buzzati (1906-1972). It is a piece I find very poignant, and not just because I also used to have a black standard poodle.)

The Personal City

by Dino Buzzati

From this city that none of you know, I send out reports, but they are never enough. Each one of you, perhaps, knows or visits other towns; and yet, no one will ever be able to live in this city of which I speak of except me. And therein lies the only indisputable interest of my dispatches: For the fact is that this city exists, and there is only one person who can provide any precise information about it. Nor is it possible for people to honestly say, “Who cares?” The fact that something exists is reason enough for the world to have to take note of it, howsoever small a thing it may be. And in this case we are talking about a whole city, a big city, a huge city, with old neighbourhoods and new ones, an endless labyrinth of streets, monuments and ruins, whose origins are lost in the dawn of history, cathedrals laden with intricate filigree carvings, parks (And at dusk the looming woodpeckers cast their shadows over the squares where the children used to play). A place where every stone, every window, every shop stands for a memory, an emotion, a life-defining moment!

The trick, of course, is to know how to describe things. For there are thousands of cities like mine throughout the world, hundreds of thousands of them; and quite often, I will admit, these urban agglomerations are inhabited by only one person, as is the case for me personally, as I mentioned. Generally speaking, though, it is as if these cities didn’t exist. How many people are there out there who are able to provide us with any satisfactory information about them? Very few. Most have no inkling of the secrets they are party to, nor would it ever occur to them to try to communicate them. Or perhaps they send out long letters packed with adjectives, but when one has finished reading them, for the most part, one is left as much in the dark as before.

But with me it’s different. Forgive me if this comes across as ridiculous boasting. It isn’t much, it’s almost nothing, but every so often, with great effort, I admit, I am able to convey an impression, however uncertain and vague, of the city which fate has assigned to me. Every once in a while, amid the many messages of mine that are not even read through to the end, there is one of them that makes itself heard. And so it happens that, out of curiosity, small groups of tourists will show up at the city gates, and I am called upon to show them around, and to answer their questions.

But how difficult it is to satisfy them. We seem to be speaking different languages. We end up having to communicate through gestures and smiles. What’s more, they are above all interested in the innermost neighbourhoods, where I can’t possibly take them: It’s completely out of the question. I myself don’t have the courage to explore that winding network of buildings, houses and hovels (the abodes of angels, or of demons?).

For this reason, I usually take these kind visitors to see the more conventional sights, the city hall, the cathedral, the Croppi Museum (that’s just what it’s called), etc., which, truth be told, are of no special interest. Hence their disappointment.

Among the members of these eager tour groups there is almost always a bureaucrat, a lawman, a superintendent, an inspector, an economist, a commissioner or something of that sort, at the very least a deputy commissioner. This person will say to me something like this:

“I wonder, sir, if you could give me some information regarding the sewage network?”

“Why?” I ask, flustered, “Is there some kind of smell?”

“No, no, on the contrary, it has nothing to do with that; but I’m interested in these matters.”

“I understand,” I say, “But I’m afraid I can’t help you. I assume there is some kind of sewage system, but I’ve never taken the time to find out about it.”

The deputy commissioner shakes his head. “Not good, not good,” he mutters with an air of superiority, “One ought to look into these things… And tell me, please, what is the annual cost of the gas supply per capita?”

“The gas supply?” (I have no idea). “There is no gas supply,” I venture, completely discrediting myself in the eyes of the visitor.

“How do you mean?”

“There’s no gas. It isn’t used here.”

“I see,” the man says icily, and refrains from further questions.

Typically, too, there is always the intellectual lady, already somewhat on in years, who is eager to display her historical knowledge. “Excuse me, but those foundations… are they late Roman? … What an interesting arrangement of pilasters… It is exactly of the kind one finds in the Propylaea of Trebizond… But you knew that already, I presume?”

“Well… you know… I… you see… to tell you the truth…”

She immediately moves on to an old wall on which are visible the remains of some archways, now filled-in.

“Oh!” she exclaims, “Delightful! That really is extremely interesting. It’s quite exceptional, is it not, to come across a Norman insertion of this kind within such a clearly Carolingian stonework? And tell me, sir, what year exactly was this most singular monument erected?”

“Um… right”, I reply, embarrassed by my ignorance, “It’s definitely quite old. It was already there in my grandfather’s time, that’s for sure. But I’m afraid I can’t give you a precise date…”

And then, more dangerous still, there’s the girl who’s hungry for new experiences. She looks about her, and immediately, with lightning speed, she picks out the most embarrassing things on view.

“And what about that street over there?” she asks, pointing towards a narrow and sinister-looking gap between two very tall rows of houses, behind whose blackened and foully-dripping walls, quite likely, crime is festering. “Where does that picturesque street lead to? Could you take me down there, sir? I’d like to take some pictures.”

But there is no way I can take her there. Even I have never ventured down that menacing flight of steps that tumbles down precipitously towards the river, and I believe I never will. Am I afraid, you ask? Maybe.

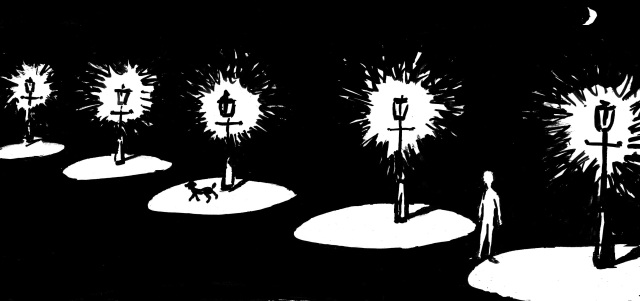

But suddenly I realize that the sun, which just a moment ago was almost suffocating in its brightness, has now disappeared behind the wild mountain ridges that loom over the city. The evening has arrived, ladies and gentlemen, with all the consequences that that implies, and trailing shadows are now rising up from the riverbank, where, already, a few streetlights are swaying in the wind. The night is almost upon us.

At this point a strange agitation comes over the tourists. They glance surreptitiously at their watches; they begin talking among themselves in low voices. In short, it’s clear they’re in a hurry to get going. My city is not exactly a cheerful place when the shadows fall, I’m afraid, and it makes outsiders feel uneasy. But I too am losing my self-assurance, I too can feel the approaching darkness bearing down upon me from the jumble of old neighbourhoods, carrying along with it some obscure and bitter weight; I too would like to leave.

“It’s late, we have to go, what a pity,” say the tourists. “Thank you for everything. It was awfully interesting.” They can’t wait to get out of here.

“Sorry, but do you think I could come with you?”

The deputy commissioner pretends to count up the seating in the cars, and then assumes a pained expression.

“I’m frightfully sorry, there’s no more room, we’re already crammed in like sardines. I’m really terribly sorry.”

“Oh, please wait, friends,” I say, not wanting to be left alone. For it isn’t easy, believe me, to spend a whole night (and the nights are long) in a big city, without any company whatsoever, even if it is our own city, built out of our own body and soul, soul and body. “Oh, please wait, don’t be in such a hurry, the streets are safer here at night, and the air is fresh and filled with fragrances, you haven’t seen anything yet, my friends, just have a little patience. If you want to fully appreciate this place, if you want to see it in all its glory, you have to wait till dusk. At dusk, ladies and gentlemen, the sun’s last stubborn rays will linger upon the passing clouds, and their glow will spread out over the rooftops, the terraces, the domes, the dormer windows, the spires of the ancient basilicas (Where the emperors were crowned), the windows of the gigantic factories, over the ruins, over the tops of the oak trees, under whose shady branches the beautiful Clorinda once slept. At this time, curls of smoke and faint voices rise up from the depths of the intersections, and the thudding rumble of machinery (While the still moonlight makes the prison courtyard seem like something out of a fairy-tale), the thudding rumble turns into an immense and harmonious choir, and mingles with our hopes and dreams. Oh, please wait!”

But it’s not true. In all honesty, it’s not a good idea to linger about these frightful tenements alone after nightfall. When it gets dark, in spite of the bright light of the streetlamps, from out the doors now step those people whom one would be better off not running into: People from long ago, dear friends with whom one used to spend all one’s time from sunrise to sunset, knowing each other’s every last thought, or else young girls, less than twenty years old, the ones that show up at the evening rendezvous, looking positively radiant. But what’s the matter with them? Why don’t they wave to me, why don’t they fling their arms around my neck? And why, instead, do they walk by me with a barely perceptible smile upon their face? Are they offended? About what? Have they forgotten everything?

No. It’s simply that the years have gone by! It’s simply that they are no longer the same people. Time –so much time!– has passed, and without realizing it, they too have been transformed, right down to their deepest innards, to their innermost brain lobes. All that’s left of them is a simulacrum, a name, that’s all, and a surname. They walk by me in silence, like larvae.

“Hi Antonio,” I say, “Hi Rita, hi Guidobaldo, how are you?” They don’t hear me, they don’t even turn their heads; the clicking of heels fades into the distance.

“Just a few more minutes, I beg of you, friends, ladies and gentlemen, your honours, your excellencies, why must you run off so soon? You haven’t seen anything yet. Soon the lights will come on, and the streets will seem like something out of the pages of certain novels, the titles of which I can’t recall. Every night at nine o’clock in the Admiralty Gardens, there is a nightingale with a diploma that sings. Pale, beautiful women will lean their elbows upon the balustrades that line the riverfront, waiting: Probably for you. In the baroque palace, the Prince will hold a party in your honour, by the light of chandeliers. Can’t you hear the violins starting up?

But it’s not true. For in this vast city that none of you know, and that none of you ever will know, in this city built out of my very life (parks buildings goodbye forevers gasometers hospitals springtimes barracks porticoes Christmases train stations statues love affairs), –Good God!– I feel so lonely. The footsteps that echo mysteriously from one house to the other whisper to me, “What are you doing? What do you want? Can’t you see it’s all useless?”

They’ve taken off. The glow of the tail lights has faded into the night, in the direction of the desert. Is there no one left? Alas, the only traces of human life around here, as you will have gathered, are nothing but ghosts, and down there, in the winding alleyways of the slums, horrible mountains of darkness are assembling. A clock on I know not what tower now strikes eleven.

No. Thank God, I’m not completely alone. There is a creature looking for me, a creature made of flesh and blood. Walking up 18th-of-May Street, under the greenish light of the streetlamps, pitter-patter, here it comes.

It’s a dog. Long hair, black, with a gentle and pensive air. It looks remarkably like Spartacus, the poodle I had about fifteen years ago. The same shape, the very same walk, the exact same resigned face.

Looks like him? It is him. It’s Spartacus, the living symbol of those far off days, which now seem happy.

He really is coming right up to me, he is fixing me with that deep and heavy gaze that dogs have, full of anxiety and reproach. In a moment, I can already picture it, he will jump up on me with yelps of joy.

But instead, when he is just two meters away, and I reach out my hand to pet him, he slips aside as if I were a stranger, and walks away.

“Spartacus!” I cry out, “Spartacus!”

But the dog doesn’t answer, doesn’t stop; doesn’t even turn his doggy head.

I watch as he grows smaller. A little black sheep, moving in and out of the successive halos of the street lamps.

“Spartacus!” I cry out again. No response. Pitter-patter. Now he’s disappeared from view.

Advertisements Share this: