I picked this book up Wednesday night, thinking I’d just take a quick skim before heading to bed. Totally wrong. De Botton’s writing lured me in with his Nesquick bit then I couldn’t put the book down.

To be honest, I was intimidated by much of my reading list this term – I haven’t studied philosophy and it always seemed very complicated and beyond my reach. It might have also been the edition of Aristotle and Plato from the last term that threw me off. The writing was inaccessible and hard to wrap my brain around.

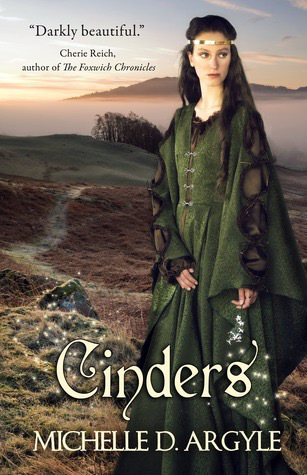

But this book… has PICTURES! And he’s funny and self-deprecating! I don’t think he’s dumbing down the material (at least, I hope not) but he’s provided fingerholds for me to grip onto and I am able to follow him through his approachable writing style. The cover of my edition has 6 philosophers’ faces, and the table of contents outline 6 chapters. Coincidence? Nope. Each chapter is a ‘consolation’ for 6 common problems and provides a philosopher to model how we can approach each challenge:

A few questions I asked myself while reading this book:

- Why these 6 particular philosophers? What moved de Botton to pick them as there must be many others who address similar topics. [After finishing the book, there seems to be a natural progression of ‘callbacks’ to the previous thinker, so there is an intellectual lineage being drawn among them, it seems]

- Does deBot see himself as the average of these 6 thinkers?

- Do the directions that these thinkers face on the cover have any meaning or am I reading too much into that?

New words I learned in the Socrates chapter: sanguine, misanthropy and intransigence. Now to find ways to drop these into regular everyday conversations. The other idea that popped up from this section was on the work needed to practice thinking systematically. It doesn’t just happen overnight, but through diligent work over time. Made me think of OW Holmes quote, “I don’t give a fig for the simplicity this side of complexity, but I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity“. In my practice as an instructor, I want to continue improving how I deliver my content and relish the work that goes into it. I don’t want to get complacent. I want to also get better at ‘studenting’ through this program and to challenge how I see the world through the books I’ll encounter in this course.

Epicurus’ chapter solves the problem of not having enough money by reframing what is essential for happiness:

- Natural and necessary:

- Friends

- Freedom

- Thought

- Food, shelter, clothes

- Natural but unnecessary:

- Grand house

- Private baths

- Banquets

- Servants

- Fish, meat

- Neither natural nor necessary:

- Fame

- Power

For Epicurus, it wasn’t about living to excess or extremes of pleasure (as his name is associated with, ex. epicurean delights), but just enough to be content. Very reasonable and achievable for all – though marketers would be out of a job if everyone adhered to this philosophy.

Seneca’s consolation for frustration is to shift your thoughts on expectations (‘unalterable realities’, ex. gravity, or a dog leashed to a cart). Fortune is a fickle goddess – one day she can give you riches and power, the next day, rip it away from you in one fell swoop. So his advice: it’s ok to enjoy what she gives, but also be ok to walk away from it all with no rage or despair. Expectations or sense of entitlement is the cause of frustrations – if you don’t have them, you can’t be disappointed. “We may be powerless to alter certain events, but we remain free to choose our attitude towards them, and it is in our spontaneous acceptance of necessity that we find our distinctive freedom.” (de Botton, p. 109)

Montaigne provides encouragement for inadequacy in the 4th chapter. He reminds the reader that kings poop too. And that you can’t judge what’s right or wrong merely from what you’re familiar with. One of the quotes he had painted on a beam of his library ceiling from Terence reads: I am a man, nothing human is foreign to me. M is a proponent of wisdom over learning – which to me means creating meaning and understanding more nuanced situations. He was a well-educated man, but he thought intellectual life was available to everybody.

The key idea from Schopenhauer’s chapter: ‘will-to-life’ (finding a partner who might be a good co-parent, but not necessarily people who will love each other in the long run). He explains to expect sorrow in relationships and appreciated Goethe’s Werther. “We must, between periods of digging in the dark, endeavour always to transform our tears into knowledge.”

Nietzsche was influenced by Schopenhauer’s idea to shy away from pain, but ended up doing a 180, and instead suggested later in his writing to embrace it as it helps one become more fulfilled. ‘Can’t enjoy sunshine without rain’ kind of thinking. The image of climbing up a steep mountain from mediocrity through pain (ascent) to the top (fulfilment) echoes back to the title of this entry, “the other side of complexity”. This philosopher suggests the benefits of wisely interpreted pain – this takes deliberate practice and learning through the envy (like Raphael), difficulty and hardship. He also didn’t dig Christianity or alcohol as these seemed to numb people versus enhance learning from pain.

So if DeBot is the average of these 6 philosophers, might he be:

- an atheist

- deeply flawed which makes him very human

- …

Need to read/listen to:

Ferriss’ interview with de Botton and the podcast notes from this show

Of note in the podcast:

43:53 – 44:48 –

When he gives a brief summary of his “Consolations of Philosophy”, the 6 thinkers he focuses on in the book who provide practical guidance for everyday pains.

1:00:00 – 1:02:50 –

A brief history of his family dynamic (“displaced, neurotic immigrants”), where he came from and context of where some of his inspiration to write and question his surroundings came from. His father was born in Egypt, in the Jewish community that got kicked out in the 1950s. Drifted around the Middle East before migrating to Switzerland, penniless and desperate. Met his future wife, who was a member of the Swiss Jewish community, whose father had recently died, her family of privileged background lost everything, When these two people met, they clung to each other and were motivated to make it in life; they had ambition and wanted to achieve great things. They build a business together, dad was a financier but retained a panicked immigrant mentally. When he finally got a Swiss passport, he was always panicked that they would take it away from him. De Botton grew up with affluence and comfort but at the same time a deep level of disturbance, fear, and anxiety in his household. Hard work, success were valued in their home, but it seems his parents did not have a good grasp of a healthy psychology. They loved the arts which he also inherited. His life’s work has been spent so far looking critically at what success and happiness means.

Advertisements Share this: