Motherhood. They say it takes a village, and let me tell you, ‘they’ were understating it. The truth is, it takes several villages, one for each child, and then one for each life stage your children will drag you through.

One of the villages I have sought constant comfort from is that of fellow mothers. Woman like me who have blithely wandered onto what we assumed were well-lit, well-trodden paths, expecting the ease and comfort promised to us by diaper and formula adverts. Instead, we find ourselves off the beaten path, and in a leaky one-person boat, traversing a vast ocean. One of the best descriptions of motherhood I’ve ever read is contained in a Huffington Post piece I found in the early hours of one of those early, hazy days with my son:

…[A]ny and all advice you receive, and there is lots of it, is barely intelligible, as if it were being shouted across some vast space from a distant, unimaginable world. It is. It’s coming to you across the water. It can be comforting or even useful, but the fact remains that no one knows what’s going on in your own boat but you and the captain. The captain is not you, by the way. Your baby has a plan for you, and you are along for the ride. […] Let the waves come, murmur a seafaring song, and know this: in any moment of new motherhood that is rough going for you, there are countless like you; there are also others for whom that very same moment was transcendent and amazing (and you’ll probably hear all about it). By the same token, in every moment that is wonderful for you, there are others for whom that very same moment was terrible. Every ship takes its own course.

One of the only things that got me through my time at sea was the village I found in others who’ve been there, or who were charting their own lonely paths on those small, secluded breastmilk/formula/coffee-powered boats. Other women. Other mothers. And because new motherhood often means you are bound to your home, and all the new essential equipment within it (bottles, sterilisers, all of the onesies in the world), I often found these sisters online. On blogs, and Facebook groups, in WhatsApp groups, and app chat rooms. And although many of the women were from lands across actual oceans, it didn’t matter. They were local to me as I was to them.

After some time, the fog of early motherhood lifted, and I began to look around. A lot of the platforms on which I depend for sisterhood and community are overwhelmingly populated by white, middle class women. Some of this can be explained by class issues: in South Africa, race is still closely linked with class and the middle and upper middle classes, who have ready access to Internet platforms, are predominantly white. But whilst it wasn’t surprising, it was a little disheartening. And in the conversations within my village, there were glaring silences. None of the mothers I was speaking to understood when I explained how, when I’m in public with my son, I make sure to talk to him about myself in the third person – as in “No, no, give mommy the shoes” – so that strangers don’t assume I’m his nanny. None of them have the questions I have about sending my son to school in our predominantly white communities and opening up to this country’s particularly toxic race relations.

I needed black mothers. And mothers of black children. In time, I’ve found some. The spaces from which I draw the community that is such an essential part of my mothering are still predominantly white and middle class. But there are notes of diversity. And where there aren’t, I’m doing my best to create them for myself and for my son.

Pregnancy, the Queen Bey way

Pregnancy, the Queen Bey way

All of which brings me to the point of this piece: Beyoncé (naturally). When she announced her pregnancy with an over-the-top Madonna-esque photo last year, there were some rumblings within the feminist communities about the gaucheness of the performativity of it all. Some asked if it was entirely helpful to contribute to our collective obsession with pregnant bodies (celebrity baby bumps, post-partum weight loss etc.) and all of our regressive notions of gender identity and maternity? Should Beyoncé have gone the route of her one-time collaborator, Chimamanda Adichie, who announced that she had carried and birthed a daughter ‘secretly’ in an interview with the Financial Times:

…I would probably have a glass of wine, but I’m breastfeeding, I’m happy to announce.” It takes me a moment to process. Adichie, 38, is famously protective of her private life. I had no idea she had a baby. Is this my world scoop? I ask. “This is the first time I’m saying it publicly. I have a lovely little girl so I feel like I haven’t slept . . . but it’s also just really lovely and strange.” Her voice has a wonderfully rich timbre. When she says “lovely” — soft and round as a peach — it feels like a gift. “I have some friends who probably don’t know I was pregnant or that I had a baby. I just feel like we live in an age when women are supposed to perform pregnancy. We don’t expect fathers to perform fatherhood. I went into hiding. I wanted it to be as personal as possible.Adichie’s ‘surprise’ announcement was hailed as an important feminist moment, an act of rebellion against the reduction of women’s public personas to their bodies and whether or not those bodies can bear children.

I quite agree. But I remember reading that and thinking how long I have loved this woman’s writing and how amazing it would be to hear her voice in the conversation on black motherhood. Not that anyone, black or otherwise, should feel obligated to share what is often an intensely private and vulnerable unravelling and remaking of the self. Still. I yearn for the voices of black motherhood. I yearn to discuss the minutiae of spit-up and potty training with women who look me, and who are mothering children who look like my son. I want to talk about what it feels like to send your child into this wide, white world, and still hold them close, and shield them from harm. I want all of it. So, when Beyoncé’s ‘performative’ pregnancy pictures broke the Internet, part of me felt relief. At last, here is something of the mainstream visual language on motherhood, embodied by a black woman. At last, here is this image of serene and tranquil motherhood, Madonna, portrayed in living colour. Which is not to say anything about Beyoncé’s pregnancy or motherhood resembles anything of my own. But it still felt good to see black motherhood represented on a global stage. It felt good to see something of the banal beauty of motherhood portrayed by a black person.

Similarly, it’s been refreshing to follow Serena Williams’s online documentation of her motherhood journey. From the banal (buying diapers) to the exhausting (3am feeds) to the overwhelming love, she’s chronicling and sharing it.

Whilst there’s nothing especially revolutionary or transgressive about what Williams and Beyoncé are doing, by simply adding their voices to these overwhelmingly white conversations, they are doing something. Being able to see some of the aspects of my experiences represented in black mothers doing the extraordinary ordinary work of motherhood makes it possible to open up about some of the uniquely hard things black mothers and mothers of children of colour must endure, along with 3am feeds and dirty diapers.

So, with all that being said, for those in my community listening for the voices of ‘other’ mothers, here are some other, non-celebrity voices that I have found helpful:

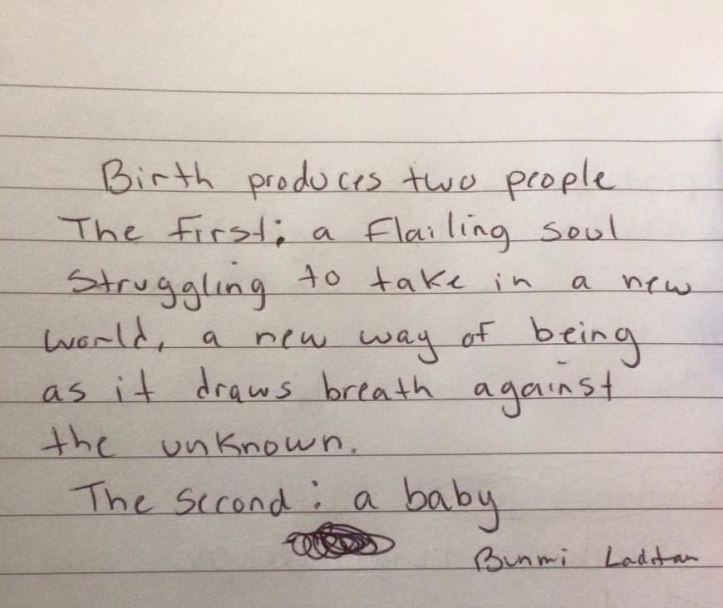

From Bunmi Laditan’s Facebook page

From Bunmi Laditan’s Facebook page

Bunmi Laditan: Bunmi began her career tweeting as the hilarious ‘Honest Toddler’, and expanded her platform to include her massively popular Facebook page, on which she posts about everything from chicken nuggets to postpartum depression and anxiety.

Black Women do Breastfeed: When I first started out my breastfeeding journey, I joined my local La Leche League’s Facebook page, which is awash with images of proud women displaying the number of weeks and months they’ve been breastfeeding and pumping. Almost all of the images were of white mothers. And then, I discovered Black Women do Breastfeed. The site aims to make black mothers who breastfeed visible to challenge the pervasive stereotype that we don’t. The images featured on their Facebook page are glorious and diverse. And for an extended breastfeeder like myself, there is plenty of camaraderie to be found.

Something to Cry About: Ah, podcasts. Any mother’s best friend, especially on those long, lonely fourth trimester nights. Something to Cry About features Brejai and Leslie, shooting the breeze about all things great (police brutality and racism in the United States) and small (what to feed toddlers). One of my favorite episodes is an early one in which they talk about the tyranny of competitive mom-social media. Do it for the ‘gram, but keep it real, is their basic message.

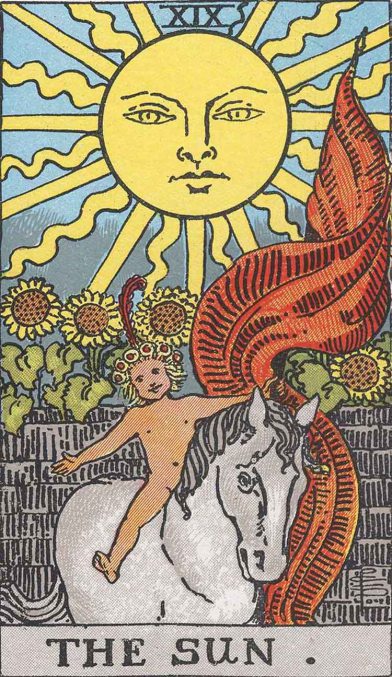

Mater Mea‘s Facebook cover image

Mater Mea‘s Facebook cover image

Mater Mea: Mater Mea features a variety of black voices and experiences, including those of black mothers who are juggling motherhood and art. There are so few spaces out there for black artists, let alone black artists who are also mothers. Mater Mea is doing important work by highlighting these stories.

Romper’s Doula Diaries: Of all of the services I had access to when I was pregnant and immediately after my son was born, I count my doula’s as the most essential. Without her, I would not have survived those first 6 weeks. But doulas are still largely seen as a luxury, only available to the elite, rather than as the essential healthcare providers that they are. Romper’s web series Doula Diaries chronicles the stories of doulas of colour and their clients. Just watch the episode above and you’ll see how important these amazing, special advocates are.

This list is by no means exhaustive. It is also not representative of any number of experiences of black motherhood. But it’s a sample of some of the voices I’ve added to my chorus, to keep sight of the joy in and amongst the work and exhaustion of raising a human being.

If you don’t find any voices that work for you, I sincerely hope you consider adding your own. You never know who it might help.

Share this: