Between Eype and West Bay, a fierce wind rocks us on the cliff path. A couple of days later, at lunch in the Watch House Café, the sound is almost deafening at times, sails flapping on high and rolling seas. On the slope above the shore, you can lean steeply and confidently into the wind. The sea is foaming, furious, tiny tumbleweeds of spume blown in cartwheels across the sand, thinning to threads of washing suds, smears along the beach.

In a high wind, I often feel as I do when watching a raging sea: a sense of awe at such naked strength and power but also extreme pleasure in the knowledge that they are, precisely, irresistible. No matter how misdirected, demented and destructive human behaviour becomes, the wind will blow, the sea will rise and fall. In such a wind, resistant, your feet solidly planted, you feel your body’s strength but also sense its limits.

In An Affair of the Heart, Dilys Powell, the celebrated film critic who also wrote several fine books about Greece, remembered a people called the Perachorans. She was married to the archaeologist Humfry Payne, who, in 1929, was appointed director of the British School of Archaeology in Athens. A year later, he initiated an excavation at Perachora, a settlement on the Gulf of Corinth, and Powell spent a good deal of time in and around the area. She wrote, ‘They grow old, they die, but they are the same. And I reflected with astonishment – for in imagination it is always oneself who is stable in an inconstant world – that I was the feather in the wind.’[1]

It’s a resonant image. Sixty years on, the world is a little more inconstant, a little less stable. Just a little. Still, it’s hardly surprising that the wind has always been a favourite literary symbol, from Homer through to the Romantic poets and beyond, seemingly apposite in a staggering variety of contexts, wind as god, wind as breath, wind as inspiration or omen or threat or simply impersonal force.

‘My thoughts were a great excitement’, W. B. Yeats remembered, ‘but when I tried to do anything with them, it was like trying to pack a balloon into a shed in a high wind.’[2] Indeed, we’ve all experienced that, no doubt. Or something like it. Or vaguely resembling it. Although lately it seems that, even when just a little excited, people tend to take to social media. Sometimes, they bring along thoughts with that excitement.

(Karen Blixen with her brother Thomas on the family farm in Kenya in the 1920s)

Karen Blixen, writing of her farm at the foot of the Ngong Hills, sited at an altitude of over six thousand feet that ‘the wind in the highlands blows steadily from the north-north-east. It is the same wind that down the coasts of Africa and Arabia, they name the Monsoon, the East Wind, which was King Solomon’s favourite horse.’[3] And it may well have been: he seems to have had 4000 to choose from, or 40000, depending on the version you settle on. A great many horses, in either case; and a great many wives and concubines too.

Having made our effortful way back from the beach—at an angle of something less than ninety degrees—we sit listening to the howling in the chimney, raising our voices a little. That in turn recalls (of course) the narrator of Ford’s The Good Soldier: ‘And I shall go on talking, in a low voice while the sea sounds in the distance and overhead the great black flood of wind polishes the bright stars.’[4] And it occurs to me to wonder, given the level of noise in this wind, just how much the narrator (‘talking in a low voice’) wanted to be heard; or rather, how much it mattered. Without getting too detailed, if his listener is the now-mad Nancy Rufford it probably doesn’t matter much at all: the murmur of a voice amidst the chorus of the wind will do.

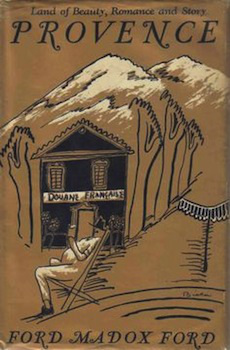

‘Wind in the Work of Ford Madox Ford’. That could be worked up into something, surely. The sentence from The Good Soldier has its traceable ancestry, primarily Ford’s own poem, ‘On Heaven’, which includes the line ‘Through the roar of the great black winds, through the sound of the sea!’[5] And more than twenty years later, at the close of Provence: From Minstrels to the Machine, another strong wind—the mistral this time—plays a central role in the drama, unless it’s a comedy:

‘And leaning back on the wind as if on an up-ended couch I clutched my béret and roared with laughter. . . .We were just under the great wall that keeps out the intolerably swift Rhone. . . . Our treasurer’s cap was flying in the air. . . . Over, into the Rhone. . . . What glorious fun. . . . The mistral sure is the wine of life. . . . Our treasurer’s wallet was flying from under an armpit beyond reach of a clutching wind . . . . Incredible humour; unparalleled buffoonery of a wind . . . . The air was full of little capricious squares, floating black against the light over the river. . . . Like a swarm of bees: thick. . . . Good fellows, bees. . . .’

A ‘delirious, panicked search’ then begins, for the scattered banknotes (those ‘little capricious squares’), for passports, for citizenship papers. The money that was to finance a year or two of rest has mostly gone. ‘But perhaps the remorseless Destiny of Provence desires thus to afflict the world with my books’, Ford concluded—as if he would ever have willingly stopped writing, mistral or no.[6]

Back in Bristol, it’s oddly calm today. Hardly a flicker in the heaped brown leaves. I type at the top of a page: ‘Calm in the Work of Ford Madox Ford’. Nothing’s come yet.

References

[1] Dilys Powell, An Affair of the Heart (London: Souvenir Press, 1958), 173.

[2] W. B. Yeats, Autobiographies (London: Macmillan, 1955), 41.

[3] Karen Blixen, Out of Africa (1937; Harmondsworth: Penguin 1987), 14.

[4] Ford Madox Ford, The Good Soldier: A Tale of Passion (1915; edited by Max Saunders, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 18.

[5] Ford Madox Ford, Collected Poems (New York: Oxford University Press, 1936), 8.

[6] Ford Madox Ford, Provence (London: Allen & Unwin, 1938), 367-368.

Share this: