“Why pots?” is the question Edmund de Waal (1964-), the famous artist and writer best known for his large porcelain installations, poses to his audience during his lecture in the Yorkshire Museum “Bright Earth, Fired Earth: Travels with Porcelain”. The answer is the talk itself, a talk in which we are invited to a journey around the world with de Waal. A talk which is thus a pilgrimage to the places where porcelain was first made and from where the values and ideas surrounding this material were first conceived and spread.

Porcelain evokes an obsession with beauty and purity. It is an obsession for the artist during the difficult process of making and it subsequently becomes an obsession for collectors. This is why porcelain is simultaneously the purest and most dangerous material in the world.

First manufactured in a small town near Beijing by its extremely poor inhabitants, porcelain was born as the only means of subsistence for these people living in a land described by a Chinese poet as a “dreadful hell”. Despite its miserable origins, porcelain’s purity did not go unnoticed and emperors from all over the world desperately sought it to build their gigantic palaces and pagodas. Their wish to show off their power and the the purity of their dynasties surpassed any ethical concerns and aesthetic taste. Rulers’ foolishness reached its peak with the German king Augustus the Strong who not only wanted porcelain for his private collection but his local manufacture too. He subsequently imprisoned a mathematician who was experimenting with methods of creating porcelain, resulting in the creation of a surrogate material that could be made in either black or white.

It was then the turn of the British to reinvent porcelain. Thanks to William Cookworthy, the first white pots were made in Plymouth. After his bankruptcy, Josiah Wedgwood, now famed as an English potter and entrepreneur, decided to set up his own porcelain business. As de Waal affirms “porcelain is not easy stuff”, and much of the porcelain raw material was obtained through colonialism, exploiting Turkish and Indian resources. Finally, white clay was transformed in jasperware by children who worked in his factory. Again, porcelain was not only a matter of purity and beauty, but also obsession and danger.

This sense of obsession and danger culminated in a derelict factory in Munich where porcelain was produced for the SS. Porcelain was manufactured in concentration camps and given as a gift or bought by visitors. Its whiteness and associative purity rendered it the perfect German material to spread Nazi ideology.

As in Germany, in the small town near Beijing where our journey started, times were changing. The arrival of the Cultural Revolution and Mao Zedong changed Ginger Jar models, and porcelain passed from being the obsession of emperors to a propagandist tool in the hands of a totalitarian system. The government commissioned clay statues of Zedong and opposing the aesthetic of the system was punishable by death. As a potter said to de Waal, “we were terrified of opening the kiln”. Making porcelain became a matter of life and death.

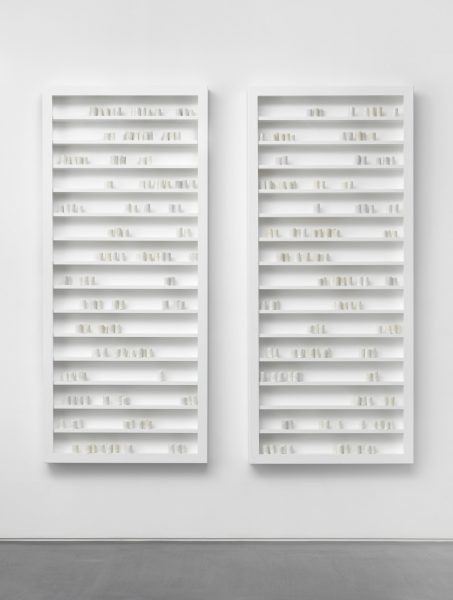

After this long journey through the history of porcelain, de Waal was commissioned to create a piece for the Theseus Temple in Vienna in 2014. This was a problematic work for him because of his Jewish identity, rendering Vienna a “city of anxiety”. Influenced by Celan’s poetry collection Lichtzwang where the poet writes about the sense of loss felt after the Holocaust, De Waal created a series of different white pots grouped as moments of the poem. The pots were inspired by a variety of porcelain creations seen on his journey, while the message of the poem was highlighted by a pair of vitrines containing the pots, suggesting detachment and immobility.

Two years later in 2016 in Berlin, De Waal started experimenting with black porcelain. Through this medium, he realised a series of free-standing massive black cases as a memorial for the writer Walter Benjamin in the Galerie Max Hetzler. The effect is simultaneously claustrophobic and overwhelming, and the shelves create a peculiar rhythm, inspired by the relationship between words, vision and materiality.

At the end of the talk, De Waal showed the audience one of his latest pieces Morandi/Edmund de Waal, commissioned by the Artipelag Museum in Stockholm in April 2017. As the name suggests, the museum is built on an archipelago surrounded by water and nature. It is likely that the work was influenced by the site and the reference to the Italian painter and printmaker Morandi. This is especially apparent in the white cases hanging from the ceiling, which seem to be suspended in a timeless space.

The artist finally suggests that if you ever happen to be in the Artipelag museum in Stockholm, you should lie on the floor of the museum during a sunny day and let the light model your perception of the white cases. In that moment you will understand that it is worth spending time with porcelain and you will find the answer to De Waal’s question “Why pots?”.

Edmund de Waal/Giorgio Morandi is showing at the Artipelag in Stockholm until October 1, 2017

Lea Marrazzo

Advertisements Share this: