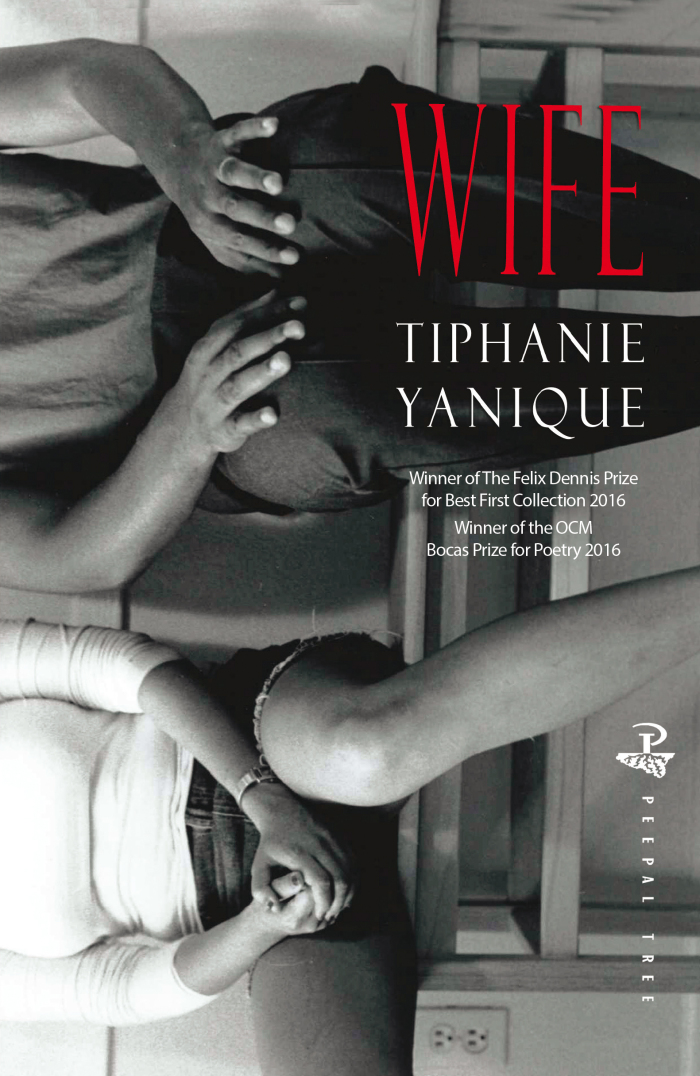

My brother comes to me

They are at the red gate

of my grandmother’s white house

The gate is taller than them both

The mother, who is my mother, is holding her son’s hand

The boy, who is my brother, is only four years old

She, our mother, is going crazy

She wants to take him with her

A blood stain has spread permanently on my brother’s white shirt

I am at the steps of the house, like a bride

I am fifteen and calling to my brother, “Come to me”

Her teeth are bared They are not pearls

“I am your mother,” she shouts

We are all crying and all our tears are all different

Our mother’s hair is a flame above us

— from Wife, © Tiphanie Yanique 2015, published by Peepal Tree Press, used by permission

This poem moves very fast to describe a moment of such power and desperation that it seemed to me on first reading that I had missed something. At the center of it all is a boy with “A blood stain” on his shirt. We don’t know how it got there, and we don’t exactly know why the women around him are acting the way they are. There’s a power struggle between the speaker and her mother, and the conflict hinges upon a choice the bleeding brother must make between them.

Of course, we know already what the boy chooses, because of the title. And because it’s the counter-intuitive choice (wouldn’t a bleeding child usually go to his mother before anyone else?) we search through the poem for clues as to why, what in the situation makes the boy’s choice different from what we’d expect.

A couple of things about language to get us there. First there are no periods but there are commas, quotation marks, and standard capitalization. To me, the missing periods make the sentences fall over on themselves, increasing the speed of the reading, especially when the sentence breaks happen in the middle of the line (“Her teeth are bared They are not pearls”) but the commas and other punctuation make sure that there is no misunderstanding, that everything, while moving very fast, is also perfectly clear.

This is reinforced by the matter-of-fact tone. Mostly the speaker relates the events in straightforward subject-verb sentences without a lot of complicated line breaks or excess detail. The gate is red, the house is white, the boy is four years old. She sees the gate and measures it against the height of the boy and his mother. She sees the shirt and knows the stain won’t come out. What’s emerging is a speaker who, in her memory at least, looks back with a ruthless, pained clarity on events that changed her life and the life of her family.

Then there’s what’s not being said, really the two most important things. First, what actually has happened to the brother? A blood stain on his white shirt could be from a nose bleed or a gunshot wound. We wonder, how desperate is this moment? A few lines later the two women are each trying to convince the boy to come to them, and if the choice is really his, then the blood must be from a wound less life-threatening than a gunshot. Still, the question hangs in our minds: how did it get there? Was it the mother? Someone else who is not in the scene? By cutting out the explanation and only providing the physical fact of the red stain on his shirt, Yanique leaves us off-balance and on edge.

One quick thing about “permanently”: it’s the only four-syllable word in the whole poem, a jarring bit of over-explanation. Of course the word literally refers to the bloodstain on the boy’s shirt that will probably not come out in the wash. But the word also reminds us that the scene itself, the terrible choice the brother has to make, will leave a permanent mark, both on him and on the woman recounting the story.

The second unanswered question concerns the mother “going crazy.” The proximity of this line to the brother’s blood at first made me think she is reacting to her son’s injury, the way many mothers would if their child were bleeding. But when we see her teeth bared and that they “are not pearls,” we start to wonder if the speaker means “crazy” literally. That would of course explain why the sister has, from the steps of the house, compelled the boy to leave his mother behind. The sneaky little pun on “going” works here because it seems that, wherever the mother is planning to take her son, it’s clear they’re also going to be going to “crazy.”

But the sister, our speaker, is now daring to replace that mother: “Come to me” is not just a suggestion. It’s the type of command a mother gives, which a child knows to obey. Meanwhile the mother’s line of dialogue “I am your mother” sounds like the self-absorbed pleading of a disappointed adolescent. We have found the sister and her mother at the moment when they exchange roles. And the speaker’s comparison of herself to a bride in the previous line makes it clear that she knows her situation is about to change permanently, as she takes on the care for her four year-old brother.

How terrible for a boy so young to have to make a choice like this! How terrible for the girl, who must urge him to make it. And how terrible for the mother, whatever her madness, who realizes that she must release the grip she has on her son’s hand in the fourth line of the poem – no four year old boy could break out of a mother’s grip if she is not somewhat willing to let him go. No wonder they all shed their different tears.

We don’t know what happens after the child goes to his sister, how the mother reacts, or how the family – sister, brother, grandmother – set about making lives for themselves in the aftermath. As I’ve said many times in this blog, a poem doesn’t have the same obligations that a story has to complete the narrative and show us what happens next. But by honing in on this terrible moment of decision and change, Yanique gives us a vivid glimpse of three lives in crisis, with a complexity that continues to unfold into the unknown. That she does so in such a small space, with such plain language, is a remarkable achievement.

Advertisements Share this: