Books bought:

Books bought:

Used via various stores via Amazon:

- Words and Names, Ernest Weekley

- Stuff I’ve Been Reading, Nick Hornby

- All Cheeses Great and Small, Alex James

- Souvenir of Canada, Douglas Coupland

From Second Story Books in Dupont Circle:

- The Oasis, Mary McCarthy

- C, Tom McCarthy

- The Black Album, Hanif Kureishi

- The Autobiography of G.K. Chesterton

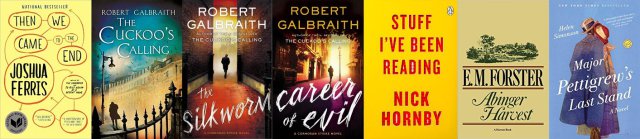

- Then We Came to the End, Joshua Ferris

- The Cuckoo’s Calling, Robert Galbraith

- The Silkworm, Robert Galbraith

- Career of Evil, Robert Galbraith

- Stuff I’ve Been Reading, Nick Hornby

- Abinger Harvest, E.M. Forster

- Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand, Helen Simonson

I added Then We Came to the End to my “to-read” list because Nick Hornby made it sound interesting in The Complete Polysyllabic Spree, and I happened upon a copy of it in a used book store not too long afterwards, so here we are. It’s a pretty solid and funny and sort of sad depiction of office life that I probably would not have “gotten” as much if I had read it while I was still in school. It really just nails that weird inanity of office small-talk–the warped reality of the workplace in which one’s willingness to engage in basically any sort of conversation to avoid working transforms events that would barely register as noteworthy in “real life” into juicy office gossip. Also blah blah blah, the interesting literary technique of using first-person plural narration.

The BBC adaptation of the Cormoran Strike books was airing around this time, and it was compelling enough that one episode per week wasn’t enough for me. I needed to know more about the characters’ mysterious backstories, damn it. As I’ve been using the Robert Galbraith/J.K. Rowling case as my go-to practical example when describing computational authorship attribution methods for years now, it was probably way past time for me to actually read the books.

Still, I have a lot of quibbles with Galbraith/Rowling’s writing style. It’s always a Thing among the people who resent the popularity of the Harry Potter books and want to prove their own superior taste in literature to claim that Rowling is an objectively Bad writer; and, like, yeah, as a kid/teenager, I was one of those people, but I think it was more to distinguish myself from the mainstream than out of any actual belief in what I was saying. I don’t actually think her style gets in the way in the HP books; you’re probably not going to read a passage and think “holy shit, that was a perfect articulation of [whatever],” but the world and the plot are compelling enough that a few too many adverbs or whatever won’t take you out of it.

In the Cormoran Strike books, however, that was…not quite the case, probably because of the genre; we’re now in the Real World, and suddenly Rowling’s obsession with physiognomy is super off-putting. Maybe she was trying to go for gritty and Dickensian–at least what I assume Dickens is like, not having actually read any–but it comes across as mean-spirited and/or cartoonish. Apparently it’s totally okay to make fun of people’s looks/weight if they’re assholes1? It is an element that’s present in the Harry Potter books–think of the physical descriptions of Pansy Parkinson, Crabbe and Goyle, Vernon and Petunia, Snape, etc.–but it’s mitigated there by some combination of the juvenile target audience, the fantasy aspect, and the overall black-and-white morality of the series, I guess.

Her hair hung limply to her shoulders and her big hands dwarfed the glass. In spite of a plainness that would have made wallflowers of other women, she radiated a great sense of self-importance.

The Cuckoo’s Calling

That seems totally uncalled-for, doesn’t it? Like someone aiming for a biting Austenian or Whartonian observation but just ending up as a kind of bully. At this point, I was wondering if this style was purposefully being used in The Cuckoo’s Calling to emphasize…something…about the modeling industry; it’s not clear if the sequels laid off that a bit or if I just got used to it.

There are still things like this in The Silkworm:

So this was why Lucy had wanted to check whether he was bringing anyone with him; this was the sort of woman she imagined him falling for, and living with for ever in a house with a magnolia tree in the front garden. Marguerite was dark, greasy skinned and morose-looking, wearing a shiny purple dress that appeared to have been bought when she was a little thinner. Strike was sure she was a divorcée. He was developing second sight on that subject.

And that’s describing a character who only appears in one chapter and is not any way related to the case. Yeah, the narration is from Strike’s perspective (3rd person, but, you know, the type that hangs close to the protagonist/is filtered through his eyes) so any misogyny or just general misanthropy can be laid on him rather than Rowling/Galbraith, I guess. It’s unclear to me how much the reader is supposed to find his gruffness/desire for privacy/irritation with social niceties charming and how much that’s meant to be an unlikable character flaw.

And then every time Rowling/Galbraith tried to aim for more literary descriptions I just felt like “oh, fuck off:”

And by the same power of will that in the army had enabled him to fall instantly asleep on bare concrete, on rocky ground, on lumpy camp beds that squeaked rusty complaints about his bulk whenever he moved, he slid smoothly into sleep like a warship sliding out on dark water.

The Silkworm

There’s also a lot of repetition of details within each book (e.g. why would Strike take Leonora’s case–oh, it’s because investigating his rich clients’ problems makes him feel sleazy and he’s touched by her honesty blah blah blah) that gets annoying and feel patronizing. It would make sense if each book were itself published serially (do we even do that anymore?), but I think you can trust the reader to remember details about the protagonist’s inner life that were explicitly spelled out a hundred pages back–more than you can trust them to remember details about the central crime, in any case. But maybe that’s because I’m more of a character-driven consumer than a plot-driven consumer? In The Silkworm, I did have to flip back to the description of the plot of Bombyx Mori and the interview with Christian Fisher, but any detail about Strike’s backstory and personality–Christ. She’s hammered in those details, alright, when they’re not vague references that clearly and sort of clumsily read as “to be revealed at a later date.”

Despite all that bitching, though, these books are weirdly compelling and I just wanted to spend all weekend curled up with them to find out “whodunit” so: mission accomplished. Every time I read an “airport book” (e.g. the Thomas Harris books, the Tom Rob Smith books, these), I find it so gripping in the “don’t want to take a break from reading or even watch TV instead” sense that it seems dumb that I don’t try to read more entries in that genre. Part of it is snobbishness–a sense that I’m too good for the genre and ought to be reading more literary things–although I guess they also do seem less likely to be soul-enriching, for lack of a better term (and god that really is an awful one), than classics or “literary fiction.” But after finishing the Strike books, I did find myself with a hole that felt like it could only be filled by the further adventures of Strike and Robin, so.

Stuff I’ve Been Reading is another collection of Nick Hornby’s columns for The Believer and it has the same appeal as The Complete Polysyllabic Spree. Not much to add there–just a really pleasant reading experience.

I stumbled upon one of those charming old clothbound copies of Abinger Harvest in a used book store in August and it felt like a real Find. It’s a collection of articles, essays, reviews, etc. that Forster wrote for various periodicals from about 1905 to 1935. As such, it’s a bit of a mixed-bag–some of the topics are too esoteric (e.g. reviews of 1920s museum exhibits, a biography of Gemistus Pletho, etc.) and some of the treatments feel too shallow. There’s definitely still some good stuff in there w.r.t. the British Empire and some of Forster’s contemporaries, and it’s interesting to be able to contrast some of these essays with Forster’s take on the same subjects in his private correspondence and his BBC talks; the essays, understandably, feel more distant and less genial. But yeah, not the most impressive of Forster’s writings and probably not something I would recommend to anyone other than Forster completionists.

Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand is one of the books I found and stole borrowed while organizing my parents’ library, and, well: it is very much a Book Group Book, you know? A love story between old people with enough commentary on class and multiculturalism to make the book club feel good about itself, but nothing radical enough to make people uncomfortable. There are some pretty ridiculous plot mechanics in the later part of the book that conveniently prevent the author from ever really having to address the legacy of colonialism in a way that might be less flattering to the protagonist and the idyllic English country lifestyle. I don’t know, maybe she’s not obligated to. The central romance was basically charming and affecting, and I was compelled to stay up late to finish it, so whatever.

Selected quotesThen We Came to the End, Joshua Ferris

Yet for all the depression no one ever quit. When someone quit, we couldn’t believe it. “I’m becoming a rafting instructor on the Colorado River,” they said. “I’m touring college towns with my garage band.” We were dumbfounded. It was like they lived on a different planet. Where had they found the derring-do? What would they do about car payments? We got together for going-away drinks on their final day and tried to hide our envy while reminding ourselves that we still had the freedom and luxury to shop indiscriminately.

Since becoming employed full-time again, he had grown aware of a phenomenon that seemed to happen only at work, or at least happened with more frequency at work than other places in life, and the phenomenon was this: one person would say something and the person listening would have positively no idea what he or she meant, but not wanting to appear rude, or worse, stupid, or alternatively, not caring to waste any more time, it was easier just to nod and laugh along than it was to pause and inquire what that person really meant. This was especially true with hallway banter and kitchen talk and other types of inconsequential daily exchanges. People were indifferent to what was said, or were preoccupied by other things, or had long ago concluded that what passed for speech during the course of a workday was mostly the babble of idiots.

Stuff I’ve Been Reading, Nick Hornby

I recently discovered that when my friend Mary has finished a book, she won’t start another for a couple of days—she wants to give her most recent reading experience a little more time to breather, before it’s suffocated by the next. This makes sense, and it’s an entirely laudable policy, I think. Those of use who read neurotically, however—to ward off boredom, and the fear of our own ignorance, and our impending deaths—can’t afford the time.

Abinger Harvest, E.M. Forster

One must behave as if one is immortal, and as if civilization is eternal. Both statements are false—I shall not survive, no more will the great globe itself—both of them must be assumed to be true if we are to go on eating and working and travelling, and keep open a few breathing holes for the human spirit.

“Liberty in England,” 1935

Perhaps only for an Englishman, and only in the nineteenth century, was such a career possible. The chivalrous free-lance, who loves justice and beauty, and is drawn to a distant quest, will doubtless be born in the future, but he will not have enough money to effectuate himself. The age of independent travel, though no one realizes it yet, is drawing to an end, and Blunt is essentially the child of that age. In the future, few of us will be able to afford a visit to the East, except in some ‘capacity,’ and as soon as one is enclosed in a capacity one’s last chance of being attractive to the Oriental disappears.

“Wilfrid Blunt,” 1920

And the obligatory T.E.L. connection:

Now that [T. E. Lawrence] is gone away, he has to come into the open, which he dreaded, he must be analysed, estimated, claimed. A legend will probably flourish, and, twisted from his true bearings even further than Nelson, Lawrence of Arabia may turn into a tattoo master’s asset, the boy scout’s hero and the girl guide’s dream.

“T. E. Lawrence,” 1935

1. It’s one of the things that bothers me about a lot of anti-Trump comedy. Obviously he doesn’t deserve to be spared the offense or whatever, but besides how stale most of the jokes are (he’s been a public figure for long enough that I’m not sure there’s anything new left to say about that hairstyle), it’s just…a weird double standard, especially when there’s so much more legitimate fodder for ridicule there. ^

Advertisements Share this: