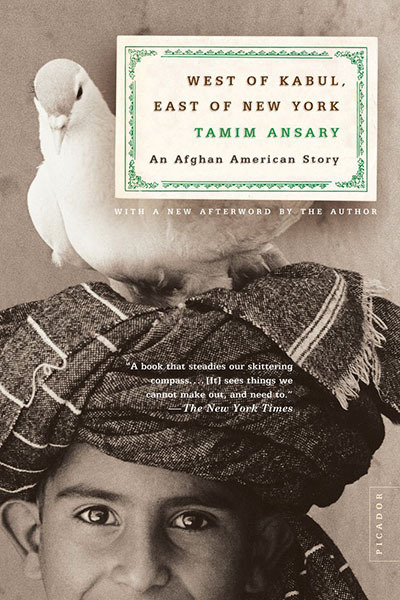

“Don’t judge a book by its cover” is a generally sound injunction. Yet sometimes the book inside a cover that catches the eye pays off the promise of the cover. One instance is the From the Land of the Green Ghosts, a memoir by Pascal Khoo Thwe of growing up in a non-Burmen tribe (Padaung) in Burma, going to college in Rangoon, and then in Cambridge. The dove on a turban of a bright-eyed brown-skinned boy on the cover of West of Kabul, East of New York: An Afghan American Story (published in 2002) is another instance both of a striking cover photo but of an excellent culture-crossing memoir. It author, Tamim Ansary, was born and spent his first years within the enclave in Kabul of what he refers to as a “clan” (and I would call an “extended family,” since I think that a “clan” has a headman), then went to a model modernizing school that pioneered co-education, then went to the United States with his Finnish-American mother, where he attended Reed College, underwent a hippie phase, tried to return via Iran to see what was going on in his homeland in the first years of Iran’s Islamic “revolution.” The book also reflects on the Taliban, and the vengances (including “nuking Afghanistan”) advocated after 9/11.

The memoir has three main parts. The first recalls “the lost world” of Ansary’s youth in an Afghanistan that he describes as not substantially differing from the Neolithic era. The second focuses on a journey across North Africa in 1979. The third part discusses his life in America, which included attempts to organize US West Coast Afghan-Americans to aid refugees from the Soviet invasion and later mujahedeen and Taliban oppressions. Appended is an e-mail Ansary wrote 9/12/01 that had very wide circulation and that clearly stated what the subcontracting/privatization mentality of the Bush administration refused to understand. The 9/12 e-mail brought Ansary to public prominence, but the quality of his book does not depend on the prophetic insights of what were the first words heard in the west after the airliner-hijacking attacks about al-Quaeda and the Taliban from a native of Afghanistan.

The first part of the book is, perhaps, the most unique contribution. Ansary attempts to explain what it was like to live in a walled family enclosure: not just the insularity (that seems suffocating to those of us socialized for privacy and autonomy), but the security of being part of a clan. “Being at home with the group gave them the satisfactions we [that is westerners] associate with solitude—ease, comfort and the freedom to let down one’s guard.” I think this is also relevant to group-oriented Japanese, to take one non-Muslim instance. The small world of the compound was one in which women, who were veiled when they ventured outside it, had freedom of movement and were not veiled.

The first part also describes his restive Finnish-American mother (met while his father was a student in the US) and some accommodation of her alienness: “The family took her in as the Permanent Guest, always to be honored, loved and cared for. Afghan society settled on treating her as an exception to the rules of gender: she was considered neither female nor male, but American.” (Such a status has recurrently been invoked for female anthropologist fieldworkers in patriarchal societies in which women have no public role.)

Ansary (at least in the retrospective gaze of the memoirist) is more aware of his privileged existence, as a son of the elite, than André Aciman was in his memoir Out of Egypt. The family name “Ansary” designates a descendant of the people who helped Mohammed escape from Medina, so has high prestige within dar-al-Islam. Ansary’s father was a poet (in a culture in which poetry is very highly valued), one of the first four Afghans who went to college in the west, a literature professor, and later a government official. The king, Mohammad Zahir Shah, and his cousin Mohammad Daoud Khan, the prime minister—were trying to modernize Afghanistan during the late-1950s and thereafter. Part of the modernization—that enraged the imams in Kandahar—was unveiling women. (In 1959, Daoud had challenged Afghanistan’s imams to show him the passage in the Qu’ran that mandated the veil. When they could not, he declared the veil un-Islamic, and the women of the royal family bared their faces in public.”) The “slippery slope” of modernization continued with co-education, in which Ansary’s sister was one of the few girls thrust into heretofore all-male classes.

Daoud sought Soviet aid, which led to a Soviet puppet regime, and the arming of Islamists (including the forerunners of al-Quaeda) by the Reagan administration. This bled the Soviets. Following the Soviet retreat, the warlord era (1989-1993) segued into Taliban domination and its concerted efforts to roll back modernization (including banning possession of transistor radios and razor blades and limitations on women far in excess of those of the traditional culture of Ansary’s childhood).

One particularly interesting point that Ansary makes is that the Taliban zealots had mostly not grown up in traditional Afghanistan, but in refugee camps inside Pakistan with a fragmented social structure, indoctrination by anti-western (anti-modernist) zealots and shamed in multiple ways, and fantasies about a past that never existed.

The second part is a darkly comic account of 1979 travel misadventures in North Africa and eastward (including great difficulty in cashing American Express travelers’ checks) with a sometimes farcical but troubling discovery of what being Muslim meant to many young Muslims inspired by Khomeni’s Islamism.

Ansary’s assimilation into American life is a more familiar story. What particularly stands out in it is his account of the profusion of Afghan American groups. No one wanted to join an existing group, assuming that all the plum leadership roles had already been taken. Better to start one’s own and hope for greater success in becoming the organization (government in exile) that the US would impose. (Analogies to Iraq are too obvious to elaborate upon.)

The book provides insight into a vanished world, and the all-too-eventful history of Afghanistan in the second half of the twentieth century, although, between Ansary’s privileged status and the lack of experience of it of those who grew up in the 1980s and thereafter, generalizability is limited. His younger brother, Riaz, who had less experience of the traditional society, is the family member who became a zealous Islamist (living in Ameica). The book also shows how Islamism looks to a non-Islamist Muslim, who was appalled by the Taliban and loathed Osama Bin-Laden long before 9/11/2001. Ansary has observed and reflected upon the uncomfortable widening divide between the postmodernist west and the antimodernist mobilization that is sometimes misidentified as “fundamentalism” (in multiple religions, not just Islam) in his life’s trajectory (to the west), in traveling, and within his (nuclear) family. What he has to say is in this engagingly written book is of interest even beyond putting a human face on the agonies of Afghan experiences.

©2006, 2017, Stephen O. Murray

Advertisements Share this: