“What is the lycanthrope, in the eye of God?”

I don’t have much experience with werewolf literature. The unfortunate examples of recent memory extends to the lame The Wolfen by Whitley Streiber and the even lamer portrayal in Stefanie Meyers’ Twilight series. Much of recent werewolf material relegates the werewolf to sidekick/nemesis status, markedly inferior to their (usually) vampire frenemies (True Blood, Underworld.)

There are a few examples of the werewolf receiving the treatment it deserves, from classics like Werewolf of London (1935), The Wolf Man (1941), and An American Werewolf in London (1981), but when we look at the pantheon of literature, there is little room for the werewolf alongside the Draculas and Frankensteins of world.

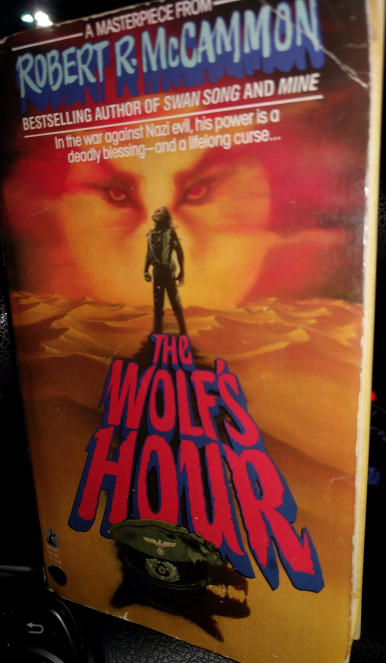

The werewolf is often depicted as a lonely, hunted creature. In Robert McCammon’s The Wolf’s Hour, the “wolf” in question also happens to be a nazi-fighting hero as well, using his powers to serve the Allies in WWII. As Michael Gallatin questions his purpose in the world, he tries to find it in fighting against the forces of brutality and evil.

I’m usually a little reticent to accept stories involving Nazis. Instead of building a villain from ground up, it’s easy to *insert Nazi here* and have a ready-made, instantly evocative force of evil. McCammon labors, though, to show you just how brutal and heartless these Nazis (and their sympathizers) are, and with the current climate threatening a resurgency of white supremacy, it’s never a bad idea to remind ourselves of the dangerous extremes brought about by ideas of racial superiority and eugenics.

At times, The Wolf’s Hour seems little more than a WWII spy novel whose hero also happens to be a werewolf. But the flashbacks that detail Gallatin’s early life, how he came to be a werewolf and lived with a pack in an isolated Russian forest, bring life and depth to a brooding hero who muses on the nature of his being while cracking skulls and crunching noses. The full horror of Nazi atrocity is on display, from the lewd cruelty that serves as entertainment for upper crust SS officers to the despairs and torments of a Nazi concentration camp. When one Nazi officer meets his end in a pit of murdered prisoners, the image is as befitting as it is horrifying.

As in Swan Song, McCammon’s apocalyptic epic, The Wolf’s Hour is impressive in its breadth of vision. But it is the peculiar paradox of werewolf Michael Gallatin that leaves the biggest impression. Often, the man turned werewolf serves to illustrate humanity’s “bestial” nature, or what we would be capable of if our humanness did not keep this primitive side in check. But as a wolf, though Michael Gallatin may serve his instincts by killing and eating prey, serving the circle of life, he never reaches the heights of cruelty attained by the Nazi machine. Indeed, the wolf is capable of seeing a world that is out of reach our of dull human senses, and appreciating that beauty in a way we could never understand.

I am reminded by a quote from Dostoevsky in The Brothers Karamazov:

“People speak sometimes about the ‘bestial’ cruelty of man, but that is terribly unjust and offensive to beasts, no animal could ever be so cruel as a man, so artfully, so artistically cruel.”

The werewolf is never as much a wolf as it is the reflection of our darker natures, the face lurking just behind the deceptive mask of humanity.

*full moons

- In 2011, McCammon published a collection of novellas that continue the adventures of Gallatin the Werewolf, called The Hunter in the Woods. I haven’t read it yet, but wouldn’t mind spending more time with the green-eyed werewolf.

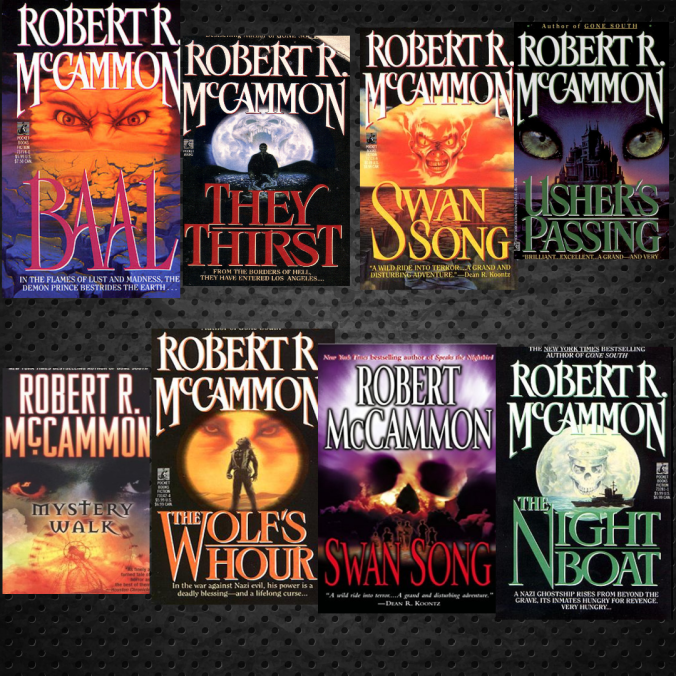

- McCammon’s artwork has an interesting continuity to it. Somebody’s always watching!

Share this: