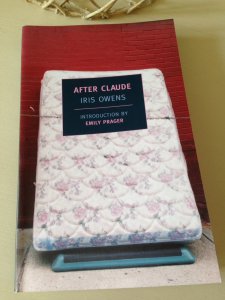

Ever since I read Dorothy Baker’s Cassandra at the Wedding back in the autumn of 2014, I’ve been searching for something similar, another hidden gem of a book with a spiky (anti-)heroine in the central role. While Iris Owens’ striking novel After Claude – first published in 1973 – doesn’t quite reach the same heights as Cassandra, for the majority of its 200 pages it comes pretty close. The story centres on a trainwreck of a woman, so outrageously forthright in her interactions with those around her that there are times when she makes Cassandra seem like a relatively normal, well-adjusted human being.

The character in question is Harriet, a fiercely intelligent lady with a razor-sharp line in cutting one-liners. The trouble is, she also displays a terrible lack of self-awareness and understanding of her impact on others. In her own mind, Harriet is a smart, considerate, lively companion; but in reality, the situation couldn’t be more different. She is lazy, rude, bitchy and relentlessly argumentative, always believing herself to be in the right whatever the circumstances or topic under discussion.

When we first meet Harriet, she is in the throes of reflecting on her very recent break-up with Claude, ‘the French rat,’ the man she has been living with for the past six months. The story is told through a series of flashbacks covering various timepoints in Harriet’s recent life – more specifically, the days leading up to her split with Claude, one or two interactions with her best friend, Maxine, and a disastrous evening spent with Claude and his friend, a French playboy names Charles.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the acrimonious nature of their break-up, Harriet paints a rather scathing picture of Claude. As far as she sees it, Claude – an assistant director of a French television news crew based in the US – is the somewhat uncommunicative, artistic type, often conveying his responses via facial expressions instead of words, especially where women are concerned.

He could talk for hours, days, but only on carefully selected topics, such as every disappointing course of his most recent meal. But discourse? Converse? Exchange ideas? Never, and certainly not with that brain-damaged segment of the population called women. (p.10)

The problem is, Harriet’s innate tendency to respond to virtually every comment with a counter-argument or snide remark has succeeded in alienating Claude to the point of no return. (The novel opens with an extended quarrel between Harriet and Claude on the artistic merits or not of a movie they’ve just seen, ‘a sort of Communist version of Christ’s life,’ as Harriet puts it. Naturally, she hated the film, and she outlines her objections with great gusto. The whole exchange is both painfully funny and sharply acerbic, a combination that sets the tone for the book itself.) Here’s a brief excerpt from one of their exchanges shortly before the split – Harriet is the first to speak.

“Are you hungry?” The creep still didn’t answer. The fact is that Claude, not having been raised by kidnappers, was habituated to regular meals, not scavenging.

“I’m not hungry.” It walked! It talked! It went to the kitchen and got itself a can of beer.

“I can’t find the opener,” he complained in that same hurt voice I’d been tolerating for two full weeks.

“Why don’t you telephone Paul Newman? I read he always wears a can opener around his neck, like a cross. Maybe he’ll lend you his.” (p. 19)

Shortly afterwards, Claude hits Harriet with the sucker punch. He wants her out of his flat by the following Monday, belongings and all; she has simply become far too difficult to live with.

“Me a bore?” I laughed, amazed that the rat would resort to such a bizarre accusation. I have since learned never to be amazed at what men will resort to when cornered by a woman’s intelligence.

“When you get an idea in your head, when you have an opinion, which is always, you’ve got to make a speech about it, not once, but ten times. If anyone manages to break in, you bury them; you grind them into little pieces with your big mouth. I’ve had it, Harriet. I want you out.” (p. 22)

The weekend ultimately ends with Harriet being driven to the Chelsea Hotel by Charles and Claude, but not before she has had an opportunity to change the locks on Claude’s apartment and been tackled by the police for trespassing on her (former) boyfriend’s property. Quite an eventful few days all in all.

Interspersed with the recollections of the dying days with Claude are passages on the only other significant relationships in Harriet’s life – those with her friends (or in the first case, ex-friend) Rhoda-Regina and Maxine. Here’s Harriet on Rhoda-Regina, her former friend from school, the girl she went travelling with some five years ago.

Rhoda-Regina had been my oldest and best friend. I’d known her almost as long as I’d known myself. We’d gone through school together, except that she, being insecure as a female, had gone on to collecting degrees. We’d sailed to Europe together, me to stay for five crucial years, during which I’d grown out of my Brooklyn chrysalis into a creature of indeterminate origins, while Rhoda-Regina had barely lasted through the summer, rushing back to her beloved highway-robber analyst like Dracula making dawn tracks to his coffin. (pp. 67-68)

Back in the story’s present day, Harriet has now succeeded in destroying any relationship she ever had with Rhoda-Regina as a result of her unreasonable behaviour as a tenant. After returning from Europe following a crisis some months earlier, Harriet turned to her old pal R-R, who agreed to take her in for a little while. Unfortunately, after another outrageous and terribly misjudged incident (this one designed to encourage the perennially uptight and stingy R-R to chill out a little), Harriet found herself out on the streets. It was at this point that she met Claude for the first time as his apartment just happened to be in the same block as Rhoda-Regina’s. So, for the last six months, Harriet has been running the gauntlet on entering and exiting the premises, desperately trying to avoid any unpleasant confrontations with R-R, her bête noire on the ground floor.

Harriet also bitches about her current best friend (quite possibly her only friend), the wealthy and pampered Maxine – both behind her back and directly to her face. Here’s a typical example – Maxine is the first to speak.

“You’re lucky to have such a wonderful skin,” she crooned, but since she didn’t look up from her gold compact, I couldn’t tell which of us was supposed to be so lucky. She glanced up. “Not a wrinkle or a blemish. What do you use?”

“Sperm,” I said, damned if I’d let her drag me into one of her beauty commercials that begin with compliments and finish with her imploring me to consider plastic surgery. (p. 46)

And here’s one of Harriet’s personal observations on Maxine, so typical of Iris Owens’ ability to pepper her writing with pointed one-liners.

There was a sufficiency of rhinestones in her thong platforms to refinance the purchase of Manhattan. (p. 45)

In essence, After Claude is a character study, a portrait of a complex woman who says what she thinks without filtering anything or sparing anyone else’s feelings. She is uber-demanding, sarcastic and combative – and yet, underneath it all, there is a vulnerable, insecure woman, someone who is terrified of being on her own, especially if it means having to survive without a man. (There are several points in the novel when Harriet tries desperately to cling on to Claude, even though she knows in her heart of hearts that their relationship is over.)

As the story proceeded to unfold, I found myself growing increasingly fond of Harriet in spite of her many flaws and annoying habits. Yes, she is a car crash on legs, but she’s also very sharp and witty with it. During the novel, she turns her irreverent gaze on a number of stereotypes – the fussy and pretentious playboy, the self-satisfied domestic goddess, the bimbo air stewardess (who really does come across as a name-dropping airhead) – all to very good effect. While I wasn’t entirely convinced by the final section of the book, in which Harriet gets involved with the members of a drugged-up hippie sex cult (very 1960s/early ‘70s), I loved the rest of it.

To finish, I’ll leave the last word to Harriet. Here she is responding to a taxi driver’s comments on her resemblance to Anne Bancroft (I guess he must have had the character of Mrs. Robinson in mind here).

“I bet a lot of people have told you, you look like Anne Bancroft,” he said, gazing into his crystal ball.

“Why? Has she been complaining to you lately?” (p. 91)

After Claude was published by NYRB Classics; personal copy

Share this: