In 2007, the Claremont Review of Books published a short essay by Mark Helprin on the literary tenor of the times. He begins the piece fairly negatively by denouncing current trends in the literary culture, but by the end of the essay he’s ended up outlining his own approach to writing by way of contrast. It’s stuck with me for a decade:

In 2007, the Claremont Review of Books published a short essay by Mark Helprin on the literary tenor of the times. He begins the piece fairly negatively by denouncing current trends in the literary culture, but by the end of the essay he’s ended up outlining his own approach to writing by way of contrast. It’s stuck with me for a decade:

One seldom encounters pure nihilism, for just as anarchists are usually very well-organized, most of what passes for nihilism is a compromise with advocacy. Present literary forms may spurn the individual, emotion, beauty, sacrifice, love, and truth, but they energetically embrace the collective, coldness of feeling, ugliness, self-assertion, contempt, and disbelief. And why? Simply because the acolytes of modernism are terribly and justly afraid. They fear that if they do not display their cynicism they will be taken for fools. They fear that if they commit to and uphold something outside the puppet channels of orthodoxy they will be mocked, that if they are open they will be attacked, that if they appreciate that which is simple and good they will foolishly have overlooked its occult corruptions, that if they stand they will be struck down, that if they love they will lose, and that if they live they will die.

As surely they will. And others of their fears are legitimate as well, so they withdraw from engagement and risk into what they believe is the safety of cynicism and mockery. The sum of their engagement is to show that they are disengaged, and they have built an elaborate edifice, which now casts a shadow over every facet of civilization, for the purpose of representing their cowardice as wisdom. Mainly to protect themselves, they write coldly, cruelly, and as if nothing matters.

But life is short, and things do matter, often more than the human heart can bear. This is an elemental truth that neither temporarily victorious nihilism, nor fashion, nor cowardice can long suppress, which is why the literary tenor of the times cannot and will not last. And which is one reason among many why one must not accept its dictates or write according to its conventions. These must and will fall, for they are subject to constant pressure as generation after generation rises in unprompted affirmation of human nature. And though perhaps none living may see the change, it is an honor to predict and await it.

Helprin’s latest novel came out at the start of October and as the release date was approaching, I went back over some of the pages I’d dog-eared in his other books. Working through those pages I came across this scene from Refiner’s Fire, which functions as a sort of fictional companion to the approach outlined above:

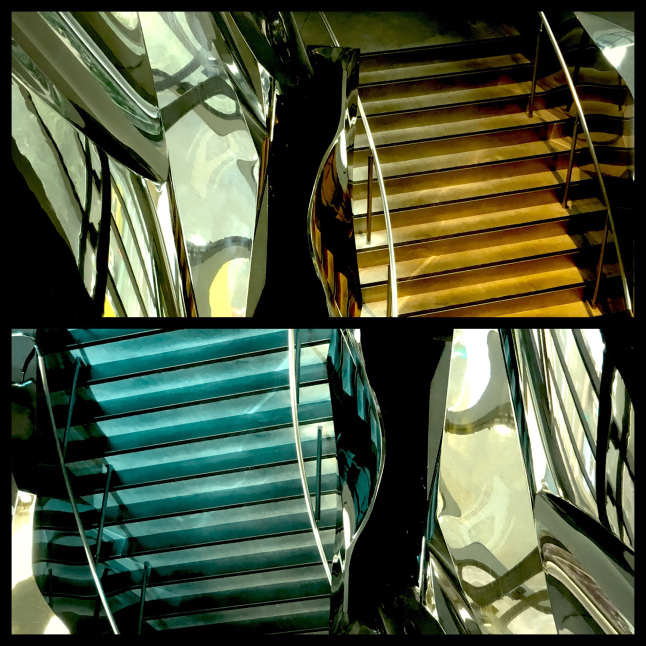

Then they started from fright, for the Captain had arrived with the grace of a ghost, and stood tall in his white uniform amid the reclining men. Seldom did he move among them. Close to seventy, he had been an admiral of the Royal Navy, who, upon retirement, could not stand to part from the sea. When the water was as smooth as a mirror, pastel by day, rich and blue-hearted by night, he grew restless.

“For those of you who would wonder,” he said, largely in pretext, “we are at the center of the sea, off the trade routes, where few have seen fit to travel. To the northwest is North America”–he pivoted and faced the various directions as he spoke, as accurately as a compass–“to the southwest, Brazil with its jutting northern chin, and then the Amazon and the white Andes; to the southeast, Africa, being worth three or four continents; to the northeast, Europe, the clockmade heart of the mechanical world. We are roped between the four, nearest the dry shelf of Spain.

“Half a thousand years ago the Spaniards, as if sprung from seed, burst in virility upon the sea and passed this point in little ships to find and conquer a new world. Since that time we have been retracing and elaborating their routes, but have none of our own. Since that time we have become as immobile as whales upon the beach–fat, shoddy, recreant, dissolving. For there is only one condition in which a man’s soul and flesh become as lean and pure as his armor; in which he finds in the art of his language and the awe of his music, unification with his own mobile limbs; in which he can find entertainment so intense as to draw him without a twitch into complete abandonment of the things of the world; in which he gathers speed and rises to his natural task as if he were an eagle destined for flight or a porpoise propelled in arcs across the water.

“Do you doubt me? Doubt not. I learned in Algeciras what this was, as I looked upon the Spanish walls which are not walls, as the lines of earth and sea were solid in one piece inviting passage, as the poverty appeared infinitely rich. I learned in the blink of an eye. I learned as the thin slapping music beat to ceilings and beams, as the percussion of dancers’ feet seemed to exhort going out beyond the harbor and into the straits–beyond the straits.

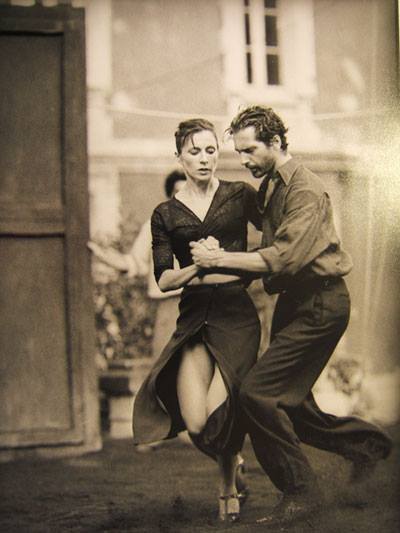

“Doubt me not. A pair of dancers was dancing twenty years ago when I thought that I had settled in. We touched at Algeciras for only a day. The secret was that they moved when they did not, and did not move when they did. They wore black, and were as concentrated as birds startled upon alarm. Their dance was like that of the bees, for God in heaven they retracted and they turned and they jugged and they jiggled, and her back was as smooth as the gust from a fan, a sweep of vanilla, and in their movements unknown to them they pointed always west and to the sea. Though they moved up and down and to right and left, the lay of their furious dance pointed west and to the sea.

“It was that way too, five hundred years ago, when from Spain’s jutting shelf they moved to fulfill the neglected task, their dancers doubtless pointing them. They found a new world with twenty-thousand miles of pine, peaks we have yet to climb, plains like seas, plants and animals humorous, terrifying, and new. Like bees, their passionate dancers pointed them. I fear that I will die before I see such dancing anew, directing us after half a thousand years outward and to the heavens, where we must go if we are to be men.

“For we are on the brink of new worlds, of infinite space curtains drawn and colored like silks, luminous and silent, moving slowly and with grace. We have come to the edge. Our children will view a terrible openness, and the vastness will change us forever and for good. I will never see it. I am seventy and I wish only to see dancers who will arise to set the right course.

“In my heart of hearts at seventy on this ship stalled in the middle of the sea and stars, I wish for the dancers who will arise as did their predecessors in one wave linked with the past, moving when they do not move, not moving when they move. When I had passed half a century, I was awakened in the fury of a dance in Algeciras. Though a captain for many years, it was that day by the curve of her back that I became a Captain and a man–when I watched history artfully running its gates with iron grasp and steel-clad direction.” (367-369)

To further fill out what Helprin’s project looks like (and to end for now), take this excerpt from In Sunlight and in Shadow. Here the same ideas are at play, but the scope is no longer the global dance of mankind throughout the centuries. Instead Harry, a soldier recently returned home after the Second World War, and Catherine are mid-conversation in a diner at four-thirty in the morning in Commack, New York, 1946:

“We were told,” she began, “that courtly love…”

“Told by whom?”

“By our professors…that courtly love is twisted.”

“How so?”

“Demeaning. Controlling.”

He straightened in his seat, lifting himself until he seemed taller, unconsciously positioning his upper body as if for a fight–not with Catherine, but with an idea. His eyes narrowed a bit as they seemed to flood with energy. “I don’t know who told you, but I do know that whoever said this was a fucking idiot who must never have seen anything, or risked anything, who thinks too much about what other people think, so much so that he’ll exterminate his real emotions and live in a world so safe it’s dead. People like that always want to show you that they’re wise and worldly, having been disillusioned, and they mock things that humanity has come to love, things that people like me–who have spent years watching soldiers blown apart and incinerated, cities razed, and women and children wailing–have learned to love like nothing else: tenderness, ceremony, courtesy, sacrifice, love, form, regard…The deeper I fell, the more I suffered, and the more I saw…the more I knew that women are the embodiment of love and the hope of all time. And to say that they neither need nor deserve protection, and that it is merely a strategy of domination, would be to misjudge the highest qualities of man while at the same time misreading the savage qualities of the world. This is what I learned and what I managed to bring out with me from hell. How shall I treat it? Love of God, love of a woman, love of a child–what else is there? Everything pales, and I’ll stake what I know against what your professors imagine, to the death, as I have. They don’t have the courage to embrace or even to recognize the real, the consequential, the beautiful, because in the end those are the things that lacerate and wound, and make you suffer incomparably, because, in the end, you lose them. (125-126)

Advertisements Share this: