August Sander was a German photography who was one of the pioneers to move portraiture beyond the studio, to make “simple, natural portraits that show the subjects in an environment corresponding to their own individuality” (Ang 2014 p.152). Using a large-format camera Sander created a typology of German Society between the First and Second World Wars.

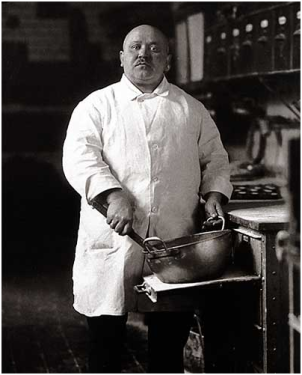

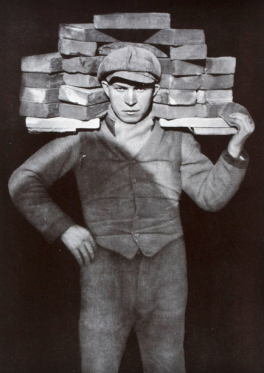

The majority of Sander’s portraits seem to feature subject that are looking at the camera, and engaging directly with the viewer. Sander’s image, The Bricklayer, is a good example of this engagement with the viewer. The bricklayer squarely faces the camera and the portrait seems formally posed, his broad shoulders fill the camera frame, denoting his strength and the physicality of his work. He is loaded down with props, that inform the viewer of his occupation, and so the simple title describing his trade seems unnecessary, although it does add greatly to Sander’s overall typology. The dark background doesn’t add any information about the subject, although it does allows the subject to stand out and impose himself on the viewer.

In contrast to The Bricklayer, in Sander’s, The Banker, the subject’s gaze is not on the viewer, but just beyond them, as if in thought. The desk creates a physical barrier along with a plethora of official banking paraphernalia (stamps and ink pads), which put him out of the reach of the ordinary man. His comfortable position affords him the time to enjoy a cigar while reviewing some bank documents. His clothes are expensive and his clean shave and neat appearrance is in keeping with his affluent position and social standing. The background reveals a door some distance away indicating a substantial office space. The main difference I see between these two photograph is where the subject is looking. The bricklayer look directly at us (and Sander), we are not above or below him in social standing. The banker does not engage with us, not everyone can an audience with him. The banker is not our equal, we have been lucky for the brief momentary glimpse into his world.

Sander’s image of The young farmers reveals a far more dynamic and possibly spontaneous photograph. The farmers are thought to be on their way to a dance in a neighbouring village and “seem to have paused, but only momentarily, to present themselves to the camera” (Jeffrey 2010 p.132). They gaze at Sander and the viewer with indifference, possibly even a hint of curiosity. Although the farmers are looking at the camera, their bodies are turned to the side creating tension. They are very much committed to their direction of travel.

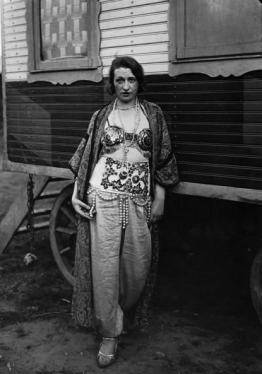

August Sander’s People of the Twentieth Century, which feature people defined by their profession, “remains one of the most sustained attempts to define individuals within their time and culture” (Clarke 1997). Sander did not discriminate. He photographed the full range of people across all walks of life, young, old, rich and poor. He had a “severe portrait style” (Jeffrey 2010 p.132), with many of his photographs appearing static and quite formal, taken at full or half-length. I find the images Sander captured out and about in the world, to be by far his more dynamic and natural works.

The images below are by August Sander.

Reference

Ang, T. (2014) Photography The Definitive Visual History, London: Dorling Kindersley.

Badger, G. (2007) The Genius of Photography: How photography has changed our lives, London: Quadrille.

Clarke, G. (1997) The Photograph, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jeffrey, I. (2010) Photography A Concise History, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

MoMA (2017) August Sander [online], available: https://www.moma.org/artists/5145 [accessed 25 Oct 2017].

Tate (2016) Tate [online], available: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/search?q=August%20sander [accessed 25 Oct 2017].

Warner Marien, M. (2010) Photography: A Cultural History, 3rd ed., London: Laurence King.

Advertisements Share this: