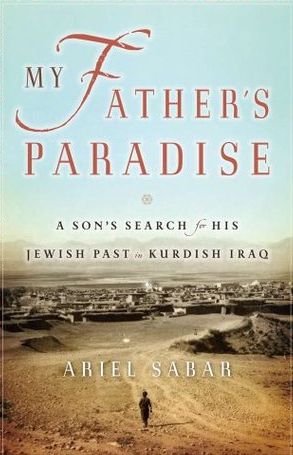

The hardcover version of Ariel Sabar’s 2008 book My Father’s Paradise is subtitled “A Son’s Search for His Jewish Past in Kurdish Iraq,” to which could be appended, “Jerusalem, Yale, and UCLA.” (The paperback shortened the subtitle to “A Son’s Search for His Family’s Past.”) The subtitular father, Yona Sabar, was born Yona Beh Sabagha in Zakho, a town in the middle of Kurdistan. Since Kurdistan is not a country, Zakho is in Iraq close to the border with Turkey.

After Israel defeated various Arab armies attempting to obliterate it in 1950, Jews across dar-al-Islam (the abode of Islam) were persecuted and many driven out. In Iraq, Kurds were second-class citizens to the ruling Sunni Arabs, and the officials in Baghdad socially doubly stigmatized Kurdish Jews, and the Jews of Zakho left between 1948 and 1950. Though not yet old enough for it, Yona was the last person bar-mitzvahed in Zakho.

The émigrés from Kurdistan (and other Jews from other Muslim countries who were “ingathered” by mounting pressure) were treated as inferior to Ashkenazi Jews (from northern/eastern Europe), Yona’s father’s heart was broken by the “return” (after 27 centuries) to Israel. Yona worked very hard, and got a scholarship to Yale, to be trained at analyzing his native language, Aramaic, once the lingua franca of the Middle East, including Nazareth (yes, “the language of Jesus”).

Arabic (a related, Semitic language) replaced Aramaic as a lingua franca roughly seven centuries ago, but the language continued to be the language of the isolated Kurdish Jews. With the “ingathering,” Aramaic became a dying language, with Hebrew-revived after not being spoken for two millennia-the language of the state of Israel.

Ariel Sabar does not mention that by 1962 Chomskyan dogma that was dominating American linguistics particularly glorified native speaker judgments of grammaticality. Maybe that is not all that relevant for Semitic philology, but Yona Sabar was also able to understand the stories he elicited and convey cultural background. This is not in any way to detract from his analytical abilities, but he was the kind of native analyst who should -and was – nurtured to explicate as well as salvage a dying language. (Yona Sabar compiled a dictionary of Neo-Aramaic and has published widely on folklore as well as linguistic analysis of his mother tongue.)

In adulthood, after being embarrassed by his foreign father through childhood and especially adolescence, Ariel came to appreciate the very high regard in which his father was held in academia and in the remnants of the Speaking-speaking ghettoes of Israel. Ariel also came to appreciate that what is now only a memory-culture of the lifeways of Jewish communities that had been in what is now Kurdistan from the eighth century B.C. to the mid-twentieth century would not be available to be elicited much longer.

So, the journalist keenly aware of his decades of filial impiety set out to write the story of his father and that of the Jews in Zakho… and of his own belated interest in his roots. I think Ariel wrote interestingly and sagaciously about all three, being appropriately hard on his own younger self’s irritation at his father’s modus operandi, before realizing the life experiences (not just Yona’s own, but his natal community’s) that made keeping your head down and preparing for the worst essential to survival.

Kurdish Jews, Christians, and Muslims got along, and the Sabars (at least so far as Ariel reports) found only nostalgia and positive memories of the Jews in Zakho, which has become prosperous since Kurdish autonomy following the first Iraq war (which began a no-fly zone on Saddam Hussein).

Though having access to documents, including old letter and diaries, and interviewing roughly a hundred people, and studying the transcripts of Yona’s elicitations of Yona’s mother’s life story, Ariel Sabar imagined a whole lot of dialogue over the course of Yona’s life. And even that from Ariel’s own two visits to Zakho – the first with his father, the second alone – are vivified by what I doubt is quoted speech. The author is literally upfront (on the first page of text) that he combined a few minor characters and that

“While this book is by and large a work of nonfiction, it is not formal history or biography. Nor is it journalism. In parts of this story where key sources had died or where memories had faded, I built on the framework of known fact and let myself imagine how the particulars of a scene or dialogue would have unfolded.”

This makes for a more vivid, readable book, but as someone interested in the history of anthropological linguistics and of fieldwork experiences, I like documentation (in endnotes is fine). There are scenes from the past in Zakho, in transit, and in Jerusalem for which I know the dialogue is imagined. My frustration (a minor and close to idiosyncratic one, I know) is the extent to which recollections in quotation marks are direct quotations. Nevertheless, I’ll conclude with a direct quotation from Ariel Sabar: Yona Sabar “sublimated homesickness into a career.”

The book won the National Book Critic Circle’s 2008 award for autobiography. Another nominee I commend is Andrew X. Pham’s The Eaves of Heaven, which is also heavily concerned with family and exile.

Sabar has more recently researched (and provided dialogue for) the stories of straight couples who met at some NYC iconic site, published as Heart of the City (2011). And a 2014 Kindle Single, The Outsider: The Life and Times of Roger Barker.

©2017, Stephen O. Murray

Advertisements Share this: