A year and half back I wrote my first blogpost about Kashmir, where I dealt in brief with the chequered history of Kashmir, the cause of anguish among the common populace and possible solutions. A year and half later, not much has changed, one might argue they have become worse. The conflict in Kashmir which began at the dawn of Independence doesn’t show signs of thawing, let alone coming to a conclusive end. The

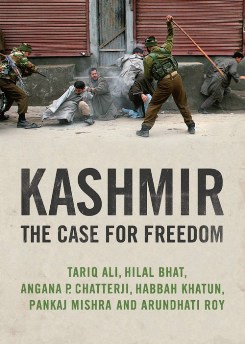

Prime Minister visited Kashmir for the second time in his tenure this Diwali, where he decided to spend time with soldiers, sparing little time for the citizens of the Valley on boil. Many would argue, ‘serves them right!’ for throwing stones at our Indian Army. But the political reality of Kashmir has a nebulous history behind it, one which India seeks to sweep under the carpet . Instead of engaging with realities, we berate our brethren from newsrooms, columns and Facebook feeds. This book titled ‘Kashmir: A case for freedom’ provides a more nuanced, and some may say a more radical view into the conflict.

I for one am not a fan of the argument that to seek to understand the reason behind something equals justifying the happening. We find these arguments being made when we debate juvenile incarceration, abolition of death penalty etc. It is important we debate these vexed, highly controversial debates freely without censure, so that tangible solutions come to the fore. This book, which is a collection of individual essays by several writers is a welcome and highly ambitious attempt to do so.

The foreword by Pankaj Mishra, acclaimed writer and scholar, outlines for us the major issues which trouble Kashmir today. The silence of Indian intellectuals and the international community in the case of Kashmir, Mishra says is defeaning. He argues that this is to be counted as a case where a highly developed democracy shies away from confronting and acknowledging its undeclared war, much like the US in all its interventions.

The ensemble of contributors to this collection of essays have achieved world-wide renown and nation-wide criticism for their writing and supposedly radical viewpoint. First up Arundhati Roy who has written bravely in the face of contempt of court and sedition charges about India and its less flattering parts, both in fiction and in non-fiction. She brings in an intrepid voice into the argument in her description of present events and egregious human rights abuses in Kashmir, both in the past and today. She weighs for the reader, the average Indian perspective best summarised by the lines ‘Tum Doodh Mangoge hum kheer deknge, tum Kashmir Mangoge hum cheer denge’. ‘India needs azadi from Kashmir, just as much as Kashmir needs azadi from India’ she seems to think.

Someone who left Pakistan after graduation, but continues to be interested and critical of its polity, Tariq Ali, brings into a distant historical perspective, tracing Kashmir’s history from the era of its Buddhist predominance to the present day disturbances which haunt India. Admittedly a left-leaning scholar and activist Ali laments what he calls ‘the Talibanisation of Kashmir’ juxtaposed against its liberal history, at the same time condemning in strongest terms the excesses of the Indian Armed Forces and the iron-hand rule of India.

The history of Kashmir is particularly interesting, which starts from being a kingdom with a majority of Hindus, which survived invasions from invaders. The invaders finally succeed in their invasion and carry out forced conversions. Later under the rule of a comparatively benevolent ruler, Zain-al –Abidin, people were allows to reconvert and given funds for constructing temples. This was followed by Mughal occupation, which has given us some of the most befitting descriptions of the picturesque valley by the Emperor Jahangir who called it ‘heaven on earth’. Afghan occupation follows a withering Mughal empire, only to be defeated by Sikhs led by Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1819. The inevitable British intervention ends the Sikh rule. Kashmir is then sold gleefully to Dogra rulers of neighbouring Jammu, for Rs. 75 lakhs, who carry out several years of repressive rule, ending with Maharaja Hari Singh.

The secular ‘People’s Conference led by Sheikh Abdullah, fueled against the repressive regime of Maharaja becomes a force to reckon with during the Pakistani invasion by tribesmen and irregulars, and the signing of treaty of accession with the Dogra Mahraja. Abdullah remains pro-India for most part, but nevertheless in incarcerated by the Indian state for two long terms. At the end of his first term Nehru dies, and Abdullah loses trust in India. However Abdullah’s People’s Conference merely demanded and continues to demand that Kashmir’s autonomy be preserved under India’s aegis.

In this compelling narrative embellished with personal encounters with the top leadership of Pakistan, makes Tariq’s chronicle of the history of Kashmir a must read, even sans his strong political opinion.

Next Angana Chatterji, historian and scholar writes poignantly about the issue of Kashmir kicking of her essay with a embarrassing question asked by a Kashmiri youth tortured in detention ‘India asks us ‘Why do you throw stones ?’ No one asks us who burned your houses and abducted your friends”. She goes to the extent of drawing a stark parallel of a post-colonial Indian state which shows a tendency for hyper-masculine militarization. And the figures are damning! Close to a million Indian personnel man Kashmir. Now two generation of Kashmiris have grown up literally in the shadow of guns. Chatterji questions double standards of India in letting Kashmiri’s peacefully protest in Delhi, but not in Kashmir, questioning therefore the lack of civil liberties in the valley.

Hilal Bhat a Kashmiri journalist’s essay, an account of life as a Kashmiri is the most abashing and heart-wrenching essay any Indian can read about his country. Bhat talks about abuses he witnessed before his eyes, how whole villages would be rounded up in the middle of the night, lined up and searched. Those who were suspects were taken off to a make-shift torture centres, from where screams would emanate. Bhat tells stories of accused people being water-boarded, their genitalia subjected to shock and things shoved into their bottoms.

Bhat, who was sent off to school in Aligarh, after his father saw him brandishing a gun, his friend had given to him, talks about his experience on a train back to Kashmir, shortly after Babri-masjid was demolished. Bhat’s friends were chucked off from running trains, when it was discovered by a bunch of kar-sevaks returning from Ayodhya that they were Kashmiris. Bhat says he survived because of the ‘Bhat’ in his name, which allowed him to claim that he was a Kashmiri Pandit.

The themes of torture, abuse and frustration of the masses come to fore through these essays. The book unequivocally calls for complete self-determination for Kashmiris, a goal which this writer does not share. But it is hard to ignore the devil-may-care attitude shown by Indian administration and the Indian armed forces, who have proceeded to award acts of human rights abuse against unarmed civilians.

The answer the book advances though radical and strategically untenable, strikes a deep chord with the reader. However the books silence or inability, despite its mention of abuses by Kashmiri militants to give space to a displaced Kashmiri Pundit’s view, sticks out like a sore thumb. No concrete measures find mention in the book.

I have for long believed that autonomy of Kashmir as opposed to complete self-determination is the way out. The discontent of Kashmiris can be channeled by giving them more power of governance. Further the militarization of the valley must be progressively withdrawn, if peace is to prevail. Decades of policing has shown us, that the valley cannot be controlled by sticks or guns. Dialogue and autonomy in the way forward. Partially repealing AFSPA in relatively peaceful areas, followed by a complete phasing out of the draconian seems to one, the only reasonable solution.

Advertisements Share this: