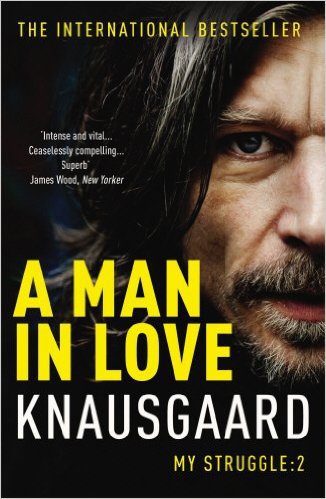

I’ve just finished reading A Man in Love, book 2 of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s 3,600-page, 6-volume autobiographic “novel,” My Struggle. This work was a sensation in Norway, where one in nine citizens has bought a copy. My Struggle has been translated into many languages; the first volume published in English by translator Don Bartlett was released in 2012 and the sixth volume will be published shortly (in 2017).

Reading My Struggle is addictive. It’s like getting inside another person’s head and following their stream of consciousness. Knausgaard’s topics range from the utterly banal details of his domestic routines (including cigarette breaks, coffee breaks, and garbage disposal) to peak moments of ecstatic happiness. There is no censorship as he analyzes his friends’ personalities and relationships, his own rocky marriage, his pitiless self-criticism and despair (which sometimes extends to suicidal thoughts), and musings about life’s existential questions and their treatment by philosophers and writers both famous and obscure.

I can think of three reasons why My Struggle has become a massive success wherever it has been published:

One evening I read a short passage in the book that demonstrated all of this. Here is what I wrote about it:

I just finished reading a description of an evening they [Karl Ove and Linda] had together. They were about to watch a movie. She gave him a small touch and looked at him and the movie was ignored. They made love instead. That’s really how it happens. And he describes this in just a few spare sentences, yet makes it clear how profound it was. He was sure they were creating another child that evening. Somehow, in those simple sentences he conveys his awe, his love for Linda, his utter physical and spiritual satisfaction, and his sense of being overwhelmed by fate in this matter of creating a new human being.

My Struggle will resonate with every reader in different ways. What I found compelling is that Knausgaard expresses the unresolveable duality and ambiguity of life in so many ways. A Man in Love is about the part of his life following his first, eight-year marriage. It is about his falling in love with Linda, and the four years soon after that, during which time they had three children.

How can there help but be conflict when a man’s daily life revolves around childcare and the endless domestic tasks of being a house-husband, yet what he burns for above all is to be alone with his writing?

His description of his first months with Linda shows a man so brimming with happiness he can’t contain it, and the couple’s friends see that they are each other’s entire world. But from this height, he falls to a state where his most frequent emotions are resentment, anger, frustration and boredom. He seems ruthless when he states that Linda needs him more than he needs her—he admits that for him writing is more important than anything, and if Linda won’t give him time for it, he will leave her. They go through a repeated cycle in which Linda suffers from depression and lethargy, and Karl Ove must do far more than his “share” of the domestic work. He does so—however unwillingly—but writes that the only outlet for his anger, the only “revenge” he can take, is to withhold his love from Linda. Yet because he still does love her, they always make up again, and the cycle repeats itself.

Almost anyone who has ever been a parent can understand Knausgaard’s conflicting thoughts about fatherhood. On the one hand, he analyzes his children’s personalities and is filled with joy, pride, and amazement about his children’s abilities and the distinctive personalities they express even as very young children. He and Linda welcome the news of each pregnancy with happiness and excitement. Yet the daily demands of taking care of children dramatically affect the couple’s relationship. Karl Ove and Linda fight about who gets time to relax and who “gets” their firstborn, Vanja—even though they both love her so much.

***

Above all I enjoyed reading Knausgaard because he doesn’t simplify life or come up with neat answers, despite his endless self-examination. He wants to be a good father, he wants to be a good person, but he often can’t. He agonizes about being two-faced—he says he can’t be himself with most people because he can’t bear conflict and therefore just says and does what he thinks others will accept. He writes about the psychological torment he feels before giving lectures about his books—even though his talks are successful, he says he’s just spouting falsehoods.

Yet he chose to write and publish My Struggle, to expose himself and those closest to him to the scrutiny of the world. The inside cover of my copy of A Man in Love quotes him saying, “I will never do anything like this again . . . I have given away my soul.”

It may have been the childhood abuse from his alcoholic father (which he sees as a major force in shaping him) that drove him to write about his life. The first book in My Struggle (entitled A Death in the Family) is about his father. (In my typical random fashion, I have read only Book 4, Dancing in the Dark—two years ago—and now, Book 2.)

But also, isn’t it true that writing is an attempt to capture our never-ending stream of thought—our very “aliveness”? Isn’t this what is behind the compulsion to write? It is for me. Karl Ove Knausgaard has done this—his My Struggle sequence of novels is an extreme case. He succeeds because of his exceptional energy and talent as a writer, the richness of his mind (I have to admit some of his philosophical digressions and analyses of Norwegian writers were beyond me), and his emotional honesty.

Further reading

The first five volumes of My Struggle has been translated into English by Don Bartlett. Martin Aitken has joined Bartlett to translate Volume 6, to be released in 2017.

You can read a fascinating interview with Don Bartlett in The Los Angeles Review of Books, in which he talks about the stamina and creativity he needed to translate My Struggle.

For an extensive review of Volume 1, A Death in the Family, read James Wood’s 2012 review in The New Yorker. This review is an excellent piece of long-form journalism. Wood felt it essential to include lengthy quotes from the book; it’s the best way to reveal the breadth, tone, and subjects of Knausgaard’s writing.

Another article in The New Yorker, Maria Bustillos’ “By Anonymous: Can a Writer Escape Vulnerability?” addresses the aftermath of the publication of My Struggle in Norway. What happens when a writer makes public the most intimate secrets of his friends’ and relatives’ relationships and afflictions? For Knausgaard, the consequences have been severe. His father’s side of the family threatened to sue him. His brother isn’t speaking to him. His wife had a nervous breakdown and their marriage almost fell apart.

He has said he wouldn’t do it again—but luckily, for us, his readers, My Struggle is out there and perhaps it can give us solace with our own struggles.

Advertisements Share this: