“For millennia, I have been evolving into this version of myself, this body. To know yours.

Because it was necessary.”

She of the Mountains is the first work by Vivek Shraya that I have read. I’ve heard of her before, both in my second-year women’s studies class where her performance of “Insensitive” with Rea Spoon and Fluffy Soufflé was discussed, and on the podcast Gender Blender. Since I first learned of her work, I have been fascinated with her ability to move between modes of expression. She is a writer, performer, and teacher; she is not limited by one career path or art form.

Academic interest brought me to Shraya’s work, but the beauty of her words will keep me there.

She of The Mountains feels immersive. Shraya uses an amalgamation of poetry and prose to weave lives together, exploring the close personal relationships of parent/child, lover/beloved. The autobiographical narrative is intertwined with a reimagining of Hindu tales, creating an experience that brings magic into the mundane, and humanity into the heavenly.

Shraya tip-toes towards “queer” as an identity marker. Recognizing the failing of words, queer is come upon as a collectivizing, freeing label. Gay doesn’t fit—it is experienced as a slur, a label spit at the character— it is used to exclude and confine, but “queer” offers possibilities. “Queer” accounts for the visible otherness that the character feels in white, gay spaces. “Queer” also accounts for the erasure of the character’s sexuality when navigating the world with his femme partner at his side. Queer has never been described to me in this way, weaving together the positive and negative affects that I have felt when trying the term on. Queer is comfortable, queer is possibility.

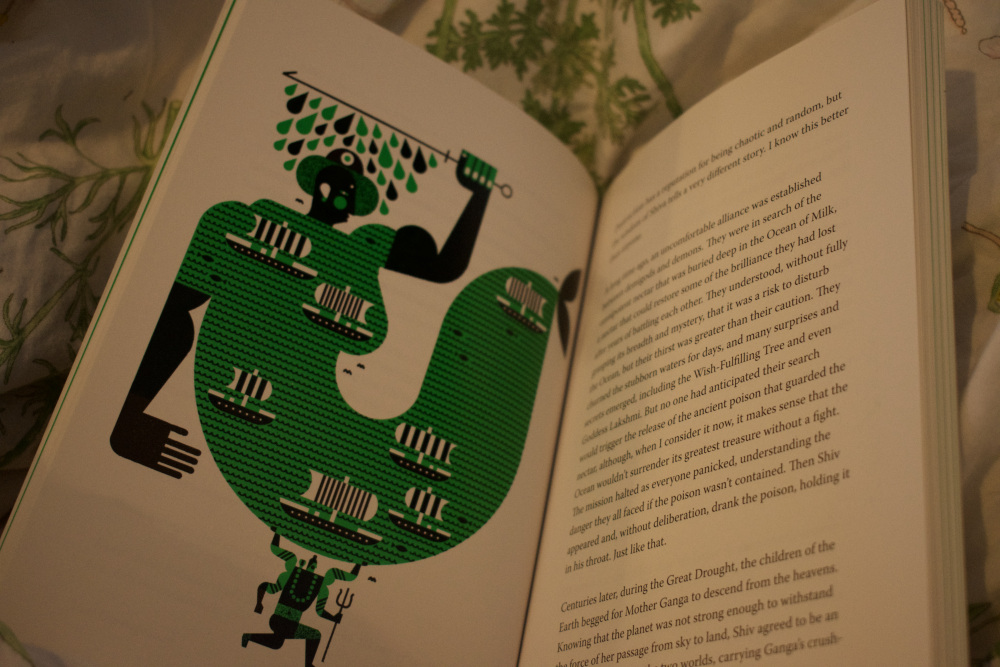

Raymond Biesinger’s illustrations complement the writing well. The images never feel too much, or too often, or too obvious, but appear just when you need them, just when you almost forgot they were there. The images play with the book’s compounding of ancient religious symbols and modernity, and of course bodies. The bodies are fragmented, broken apart and put together again imperfectly, just as the characters are, with their pain, with an elephant head.

Shraya decanter’s whiteness at every opportunity. She reminds me that I am a voyeur, I am looking into brown love, that the story is not meant for me.

The book is personal, it is the writer’s fictionalized journey of working to understand self. When reading, some parts felt as though they were calls to gather in something greater, a collectivity that moves through shared experiences, compassionate words and affects. Shraya weaves images onto paper of feelings that I have felt but never said.

Shraya destabilizes what a love story can be, using different kinds of love (parent/child), different kinds of people (god/human), and different kinds of relationships.

It is hard for me to find a fault with this book, as every part seems to work together to create a whole that doesn’t necessitate cohesion. Each part is a fragmented meditation on what it means to be queer, to be brown, to be in love and to love. She of the Mountains queers the topics that it takes up, and queers conventional understandings of what love can be.

Advertisements Share this: