When the author of the bestselling Arcadian series, Greig Beck, described my most recent book as “cinematic and evocative” I might have done a little happy dance. It was Greig Beck and cinematic is good, right? But what exactly do we mean when we say a story is cinematic?

I ask Kathryn Burnett, screenwriter, teacher, and script consultant for feature films such as The Devil’s Rock and Love Birds, for her view. “A cinematic idea to me is one that is suited to the film medium, which means it can be told in images,” she says. “In addition to this, the problem the protagonist is dealing with should be a really big deal to them. If it’s not the biggest crisis in their life thus far ‒ then what is? And why aren’t we hearing that story?”

Kathryn Burnett

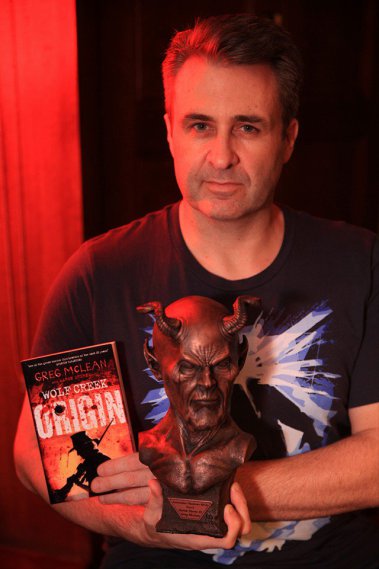

I think about my book, Into the Mist, and its antagonist, a primordial flesh-eating monster: definitely the biggest crisis in my protagonist’s life thus far. But Aaron Sterns, screenwriter of Wolf Creek 2 and author of the prequel novel Wolf Creek: Origin, brings me back to earth with his more market-oriented perspective. “In a general sense, describing someone’s fiction as cinematic may just mean the writer’s presented a clear, high-concept idea that is universal yet unique enough to warrant being adapted to film (with its high costs and often necessity to appeal to a wider market). But it’s more likely that the fictional work utilises defined set-pieces in clear blocks of the plot ‒ arranged similarly to the scenes in a film for instance, instead of flitting back and forth between locations, time zones, or the consciousness of different characters as fiction can do.”

Aaron Sterns

It’s true, to do I tend to switch narrators often in my writing, and I’ll transition quickly from one scene to the next as you might see in a film. But if that were all that was required, wouldn’t all novels be described as cinematic?

“It might mean that there’s a lot of action as opposed to internal reflection,” Aaron adds. It’s a point Kathryn makes, too. “You need characters that do stuff rather than think about stuff.” Lynne Hansen, the award-winning director-screenwriter of short film Chomp, agrees. “The stories that work best for film are those that have successfully figured out how to represent internal struggles in the external world.”

Kathryn explains, “If the idea relies entirely on dialogue or descriptions of your character’s inner life then it’s going to be a real challenge to bring it to life in a screenplay.

One of the biggest differences between writing prose and writing for the screen is that in a screenplay you don’t tell us what the characters are thinking or feeling – you have to show it in their actions.”

Aha! Show-not-tell. That’s a concept we novelists understand. Greig, arguably one of Australia’s best novelists, tells an insightful story about a presentation on descriptive language in writing, which he gave to a group of school kids a few years ago.

“I used comic books to illustrate my points,” he explains. “I first showed some Batman comics from the 1960s – poorly drawn characters and scenes – Bam! Kapow! Oof! – so many comic panels dominated by dialogue boxes and scene explanations. Then I showed some modern Batman comics – there were few words, but the magnificent artwork was breathtaking. The realistic facial features with an expression illustrated just with the curve of a lip or clenched jaw. The menacing scenery set the mood and even the minuscule details such as raindrops splashing into puddles of reflected images.

Greig Beck

“This is like the difference between writing a novel and writing a scene for a film script – in a book, the author only has words to create everything about the scene. But in a script, you don’t get several paragraphs to ‘paint the sensory image’, and more is only implied. The rest is left to the director to conjure the magic with film.”

Daryl Belbin emphasises the role of the reader and what they bring to the experience. A Welsh writer, screenwriter and filmmaker now living in New Zealand, Daryl says, “the reader is an intrinsic ingredient of the storytelling process as they take in the information given, make sense of it and then reconstruct it as moving images and sound in their minds. They could be seen as kind of a magical TV set, where the writer’s signal is transmitted and the reader receives and projects the signal onto the screen of their mind.”

Daryl believes even the smallest details can contribute to that experience, right down to the writer’s word choice and the relative combination of those words. “Words are elaborate symbols that conjure up images and invoke memories. These symbols are imbued with many different characteristics, which can be quite subjective. Clever use of these symbols can easily transport the reader to the world of the story.”

So, do some stories lend themselves better to film?

Daryl has some thoughts on this. To determine if a piece of writing will make a good film, Daryl suggests asking whether the reader loses themselves in the world while reading.

Lee Murray

“When I read scripts,” says Daryl, “if I’m not aware of the nuts and bolts while reading, I think of it as cinematic. Obviously, producers, directors and directors of productions are readers themselves, and if they can easily see the story in their minds then they can easily frame it on camera.”

Aaron reminds me that it’s not just books inspiring film, and that nowadays intellectual property tends to be morphing itself across the mediums, which is why so many graphic novels are adapted to film and vice versa. It’s the reason Aaron tries to develop his work across the fields. “I’m currently adapting my novella Vanguard for film,” he says. “I’m also working on a novel originally published as a short story, expanded into a screenplay due to a producer’s interest, and is now being even further expanded as a novel. Each requires a different focus on the overall story, but each captures a different part of the whole world too. Film-makers are always hungry for solid material, and having an idea already be validated by appearing in fiction or comic form can be almost a proving ground.”

A proving ground? So if my book is cinematic and evocative can I expect a filmmaker to show some interest? My heart skips a beat. Not so fast, cautions Greig. Over the years, he’s had around a dozen studio calls regarding translating his books to the screen. He was even encouraged to create a Spec Script for Beneath the Dark Ice, a document he says is still kicking around after he spent months making the transition to a shorter and sharper dialogue-driven writing style. “Plus there was the getting my head around all the proper formatting techniques,” he says. “Fade-in/out, parentheticals, intercuts, etcetera, etcetera, and etcetera!”

‘Into The Mist’ – Lee Murray

This is all very good in theory, but how exactly does a director translate the written word onto the screen? There’s been a lot of talk of magic, which is all very well, but how is it done in practice?

Lynne describes how she plans to achieve that in her current project, a horror/thriller feature based on a novel by four-time Bram Stoker Award nominee Jeff Strand. “It’s about a group of strangers who are trapped in a walk-in freezer during a terrorist attack on a grocery store. The entire film takes place in real time inside a 12 by 16 [ft.] walk-in freezer. You don’t get the internal monologue of the book. I had to use dialogue and action to create the same emotions. On the technical side, I’m building a freezer set that will allow us to move walls to execute camera moves that tell the story in the most effective manner. We’re doing all of this to make the audience feel both part of a larger world and right down in there with these ten people trapped in the freezer. Braver, in-your-face cinematic storytelling ‒ that’s what we’re after with Cold Dead Hands.”

There are no freezers in my novel, no walls even, since the story is set in forest. There’s nothing else for it: I have to ask Greig exactly what he meant. I message him and he pings me back.

“In my writing, I’m influenced as much by movies as I am by books,” he says. “I love the big budget blockbusters with extravagant action scenes, so when I’m reading a book or am writing a scene, I can see it played out in my head. Some authors are able to create that movie-type aspect better than others, as they use their writing to conjure settings, action sequences and conflict/interaction magnificently. Into the Mist was a book that made those scenes materialise for me – I could see and feel the sensations of that misty forest every step of the way.”

His explanation leaves me with a hopeful soft focus glow, even if getting a book to screen can involve a lot of tyre kicking with nothing concrete to show for it.

“Every author would like to see their works on the screen, and smaller studios are always on the hunt for works to translate, so who knows for the future?” he concludes.

I don’t get the message: I’m already online checking out a dress for the Oscars.

Lee Murray – Greig Beck – Kathryn Burnett – Aaron Sterns – Daryl Belbin – Lynne Hansen

Advertisements Share this: