Around us may be windowless walls of brick and rebar, but give us a story and immediately an arc of the horizon appears. What if we had many stories?

Magnificent arrangements of books inspire awe in most bibliophiles. Awe—the feeling of solemn and reverential wonder, tinged with latent fear, inspired by what is terribly sublime and majestic in nature (OED)—really is the right word. Public libraries, bookshops, private collections, even a carefully positioned mess of tattered paperbacks on a stack of plastic shelves in a café: they are magical vistas of possibility.

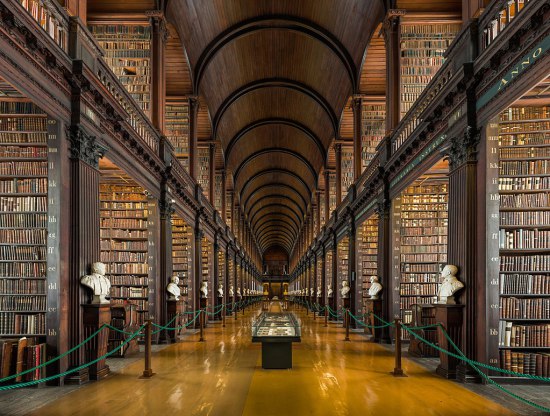

Library of Trinity College Dublin, by Diliff (Own work) CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Of course, the grander the bookscape, the more likely it will overawe any visitor with sheer Olympian attitude, for where does one begin?

Occasionally, even if we were to just dip into a book, then into a another, and so on, it would take years before we wormed our pathetic way through all the covers. (For example, it would take approximately 35 years in the case of the library of Trinity College Dublin, if we were to spend a minute a book, eight hours a day, every day of the year.) The thought makes me go hot and cold and shaky—the potential knowledge, the tales, the imagination, the human ingenuity waiting within the pages, the Diderot-Deridda-Dostoevsky, and only a finite amount of time before my hands will no longer be able to reach beyond the inside walls of an ash-filled urn, let alone hold a book. The desperation!

This is when awe takes on its obsolete sense of immediate and active fear; terror, dread, and as such approaches the obsolete sense of horror, meaning a feeling of awe or reverent fear (without any suggestion of repugnance). Which is appropriate, as horror comes from the same Latin root as the word horripilation, meaning erection of the hairs on the skin by contraction of the cutaneous muscles. In other words: goose-bumps.

(If you have never had goose-bumps upon entering a library, this article may appear strangely vapid.)

There are some bookscapes that leave me apathetic: starkly-lit hypermodern storefronts, a thumbnail list of generic covers on a website, a pristine collection of hardbacks that are off-limits for fear of damage. Their common factor is a neat, trimmed flatness. A featureless landscape provides no anchor for the eye, or in the case of books, for the imagination.

Alberto Manguel, in his Library at Night, addresses the issue of a library’s shape (and therefore, partially, of what I call a bookscape) in his chapter The Library as Space.

Quote: We don’t read books in the same way sitting inside a circle or inside a square, in a room with a low ceiling or in one with high rafters. And the mental atmosphere we create in the act of reading, the imaginary space we construct when we lose ourselves in the pages of a book, is confirmed or refuted by the physical space of the library, and is affected by the distance of the shelves, the crowding or paucity of books, by qualities of scent and touch and by the varying degrees of light and shade. … There are readers who enjoy trapping a story within the confines of a tiny enclosure; others for whom a round, vast, public space better allows them to imagine the text stretching out towards far horizons; others still who find pleasure in a maze of rooms through which they can wander, chapter after chapter.

Manguel asserts that a library space affects the mental space within which we read. Whilst the library space is as a physical entity—with measurable distances, dust quantities, temperatures and lighting—it will also affect each person differently, and therefore it is partially unknowable to anyone but the reader experiencing it, in the same way that a person’s mental space is completely unknowable.

In general, everyone has their own feng shui theory of furniture arrangement—practical, aesthetic, quaint; some people even fantasise of exact architectural constructions which would realise their vision of an ideal home or workroom. Bibliophiles theorise on bookscapes in concrete terms. The Quote, however, doesn’t pinpoint a clear relationship between library and mental spaces, nor does it say more than is true of any space and any action taking place within it: the space affects the action, and the action affects how the space is perceived. A little lower down in the same chapter, Manguel is more specific.

Square spaces contain and dissect; circular spaces proclaim continuity; other shapes evoke other qualities.

My experience of reading in diverse angular and curved libraries is limited—especially under stable, repeatable conditions—but I’d be curious to test various shapes. Failing that, I’m willing to imagine myself reading Borges’s Book of Sand in his Library of Babel, wandering in Eco’s library on the top floor of the Aedificium in The Name of the Rose or following around Terry Pratchett’s orang-utan Librarian in his Discworld series. Perhaps that is why stories that reimagine libraries remain popular—the curiosity about new reading spaces exceeds the available opportunities to experience them in person.

(Something I just discovered: apparently these days books by the metre can not only be bought, but also rented, to give bare areas the éclat they deserve.)

Of the fictive libraries Manguel mentions, I was most taken by the vision of an eighteenth century French neoclassical architect.

Boulle’s proposed library

Etienne-Louis Boullée, one of the most imaginative architects of all time, proposed in 1785 a long, high-roofed gallery of gigantic proportions, inspired by the ruins of Ancient Greece, in which the rectangle of the gallery would be topped by an arched ceiling, and readers would wander up and down long, terraced mezzanines in search of their volume of choice.

My preferred reading place would be behind one of those columns, left or right, or at the far end, next to that statue in the very centre of the semi-circle. I would also like to make my bed on the floor, surrounded by books, blanketed by stars. There I would sleep every night, ensconced in awe.

Share this: