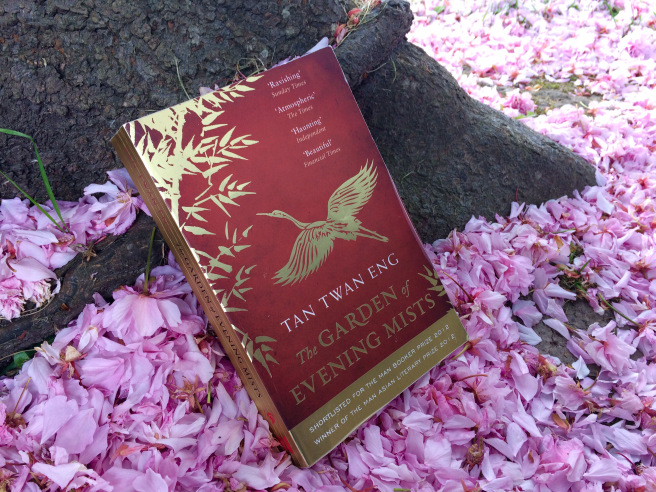

After a brief tour of Oceania, my Booktrotting tour now begins its Asian leg, with a window on post-war Malaysia in Tan Twan Eng’s The Garden of Evening Mists.

It was Sunday, and the tea-fields were deserted. In the valleys, the points of light from the farmhouses were as faint as stars behind a weave of clouds. The moon was retreating behind the mountains, the same moon I had seen at almost every dawn in the camp. So long after my imprisonment, there were still moments when I found it difficult to believe that the war was over, that I had survived.

It is 1951, and Malaya is beginning to undo the damage wrought by its brutal Second World War occupation by Imperial Japan. Its people are recovering too, and for Teoh Yun Ling, a former detainee in a Japanese internment camp, that means constructing a memorial garden for her sister, who perished where Yun Ling survived.

Her endeavours lead her to the mist-bound slopes of Malaya’s mountain highlands, and to the door of Nakamura Aritomo: once the chief gardener to Emperor Hirohito himself, now living in exile in the land his own people ravaged. Under Aritomo’s guidance, Yun Ling learns how to bring to life the garden her sister always dreamt of—and all the while comes to terms with the horrors of her past.

Bharat Tea Plantation, Bjørn Christian Tørrissen / CC-BY-SA-3.0

Bharat Tea Plantation, Bjørn Christian Tørrissen / CC-BY-SA-3.0

When I started my Booktrotting project, The Garden of Evening Mists was exactly the kind of novel I hoped I would encounter. As a story it’s spellbinding, a rich weave of complex characters and emotions that unfolds delicately through Yun Ling’s pain-driven narrative; and, spanning as it does some of the most seismic events in the region’s recent past, I could hardly have asked for a better grounding in the historical foundations of modern Malaysia.

Although the events of this novel are huge in scale (covering not only the Pacific War but also the communist guerrilla “Emergency” that followed) its thematic focus is relatively small. Tan treats the sweep of Malaya’s military struggles as more of a backdrop than the cornerstone of his plot, training his focus instead on the ground-level story of Yun Ling—on the raw grief of her sister’s death, her hatred of the Japanese, and the thorny duality of her relationship with Aritomo.

In that sense, The Garden of Evening Mists is very reminiscent of Evelio Rosero’s The Armies. As Rosero used his narrator’s agony at the loss of his wife to reflect the wider damage wrought on Colombia by its conflict, so too does Tan Twan Eng seem to be speaking in terms much larger than an individual character when it comes to the enduring effects Yun Ling’s internment had upon her.

Penang, Tys / CC-BY-SA-3.0

Penang, Tys / CC-BY-SA-3.0

Throughout The Garden of Evening Mists many characters remark on Yun Ling’s understandable anger towards her captors, and how her inability to move beyond that stage of grief is not only preventing her emotional wounds from healing, but is also causing her more pain the longer she dwells on it. Indeed, at the beginning of the story Tan reveals that this has already cost Yun Ling her job: as a state prosecutor, she was fired after publicly criticising the colonial British government for acting too leniently towards Japanese war criminals.

But the irony here is that Yun Ling is doomed to leave her past behind, whether she wants to or not—she suffers from aphasia, a brain condition robbing her of her memories. The other characters who urge her to let go are entirely unaware that the reason Yun Ling clings so fiercely to her past, and especially to its most traumatising scenes, is that the resulting pain is the only thing sharp enough to keep her from losing such an integral part of herself.

In an interview with bookbrowse.com, Tan described Malaysia as “very forgiving—or forgetful” when it comes to the legacy of the Japanese Occupation; he added that following the release of his debut novel The Gift of Rain, set in wartime Penang, many Malaysian readers said that they had been unaware of story’s historical events prior to reading it.

(In an interesting side-note, Tan also advocates the educational preservation of Malaysia’s historic and colonial-era buildings, which he feels are too readily discarded to make space for modern developments like the iconic Petronas Towers.)

It’s not hard, then, to imagine that The Garden of Evening Mists was written in response to this. Through Yun Ling and the characters surrounding her, Tan calls for a balance between the pain of remembrance and the dangers of being all too hasty to forget; a balance that allows Malaysia to look to its future without disregarding the lessons of its past. For whilst the horrors of the Japanese Occupation are inevitably hard to hold on to, the alternative—losing those memories forever—would be far, far worse.

Petronas Towers, McKay Savage / CC-BY-2.0

Petronas Towers, McKay Savage / CC-BY-2.0

The next stop on my journey takes me northwards to Japan itself, and the setting of Snow Country by 1968 Nobel Prize-winner Yasunari Kawabata.

Advertisements Share this:- Share