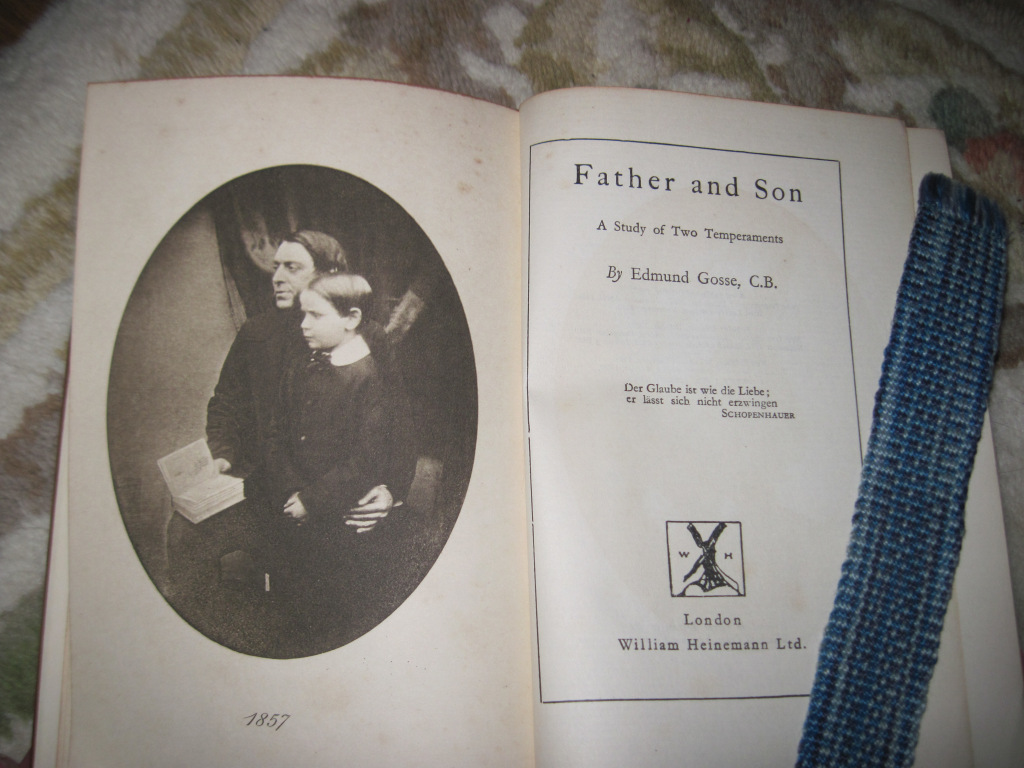

I can’t believe how long it’s taken me to get to this splendid evocation of 1850s–60s family life in an extreme religious sect. I’d known about Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son (1907) for ages, and even owned a copy. Two of its early incidents – the son’s anticlimactic birth announcement in the father’s diary, and the throwing out of a forbidden Christmas pudding – were famously appropriated by Peter Carey for creating Oscar’s backstory in his Booker Prize-winning novel Oscar and Lucinda (1988), which I read in 2008 but didn’t much like. I was reminded of that literary debt when I worked for King’s College London’s library system and did a summer placement in the Special Collections department in 2011. For my “In the Spotlight” article about a book in particular need of conservation, I chose Philip Henry Gosse’s Omphalos, his well-meaning but half-baked contribution to the Victorian science versus religion debate, and did a lot of secondary reading about the Gosses and their milieu.

The book’s subtitle, “A Study of Two Temperaments,” gives an idea of the angle Gosse takes here: this is not a straightforward biography (after all, he’d already written his father’s life story in 1890) or a comprehensive memoir, but a snapshot of his early years and an emotional unpicking of the personality clash that results from fundamentally different approaches to life. While Gosse père (1810–88) was a devoted naturalist as well as a dogged believer in the literal truth of the Bible, even in adolescence his son (1849–1928) was a literature aficionado and troubled skeptic. Philip Gosse was a minister with the Plymouth Brethren and married late, at 38; his wife was 42, very late for contemplating motherhood in those days. Like Thomas Hardy, the infant Edmund was presumed dead at birth and set aside, so it’s thanks to keen-eyed nurses that we have these two late Victorians’ significant literary output today.

Although his first word was “book” and he could read by age four, Edmund was initially forbidden to read fiction. His mother quashed her own love of making up stories because she believed fiction was in some way sinful. It was always taken for granted that Edmund would follow his father into the ministry, and early on he had a sense of a split self: the external persona he put on to please his parents, and the deeper self that struggled to divine its purpose. He would cheekily test the limits of his familial faith by petitioning the Almighty for an expensive toy that he ‘needed’ and praying to a wooden chair to see if he’d be struck down for idolatry. The absurdity of such scenes is a welcome foil to the sadness of his mother’s death when Gosse was just seven. A year later the boy and his father moved from London to Devon, where both were captivated by the sea. (Indeed, if Philip Gosse is remembered as a natural historian today, it’s largely for his work on marine life – he discovered a new genus of sea anemones in 1859.) After Philip remarried, Edmund began attending a weekday boarding school and fell in love with literature, especially Shakespeare and the Romantic poets.

There’s a stretch of the book at about the two-thirds point that I found less compelling; much of it describes the other members of his father’s congregation (“the saints”) and the tedium of Sundays. It’s also a shame there isn’t a brief afterword that continues the story through to his father’s death. But for much of its length this is a riveting investigation of how the conflict between reason and religion plays out both within individual souls and between family members. The purpose here is to chart the course that led him out of religion and made the supernatural rift between him and his father permanent by the time he was 15 or so, and Gosse fulfills that aim admirably. In doing so he maintains a delicately balanced tone: Although he vividly recreates funny moments from his childhood, he also makes clear-eyed, scathing assessments of a religion that is ostensibly based on love but all too often veers towards judgment instead:

Here was perfect purity, perfect intrepidity, perfect abnegation; yet here was also narrowness, isolation, an absence of perspective, let it be boldly admitted, an absence of humanity. And there was a curious mixture of humbleness and arrogance; entire resignation to the will of God and not less entire disdain of the judgment and opinion of God.

[H]e allowed the turbid volume of superstition to drown the delicate stream of reason.

He who was so tender-hearted that he could not bear to witness the pain or distress of any person, however disagreeable or undeserving, was quite acquiescent in believing that God would punish human beings, in millions, for ever, for a purely intellectual error of comprehension.

Even so, this is a loving portrait, as well as a nuanced one, and a model of how to write family memoir. I enjoyed it immensely, and will no doubt read it again.

My rating:

Further reading:

- Glimpses of the Wonderful: The Life of Philip Henry Gosse 1810–1888 by Ann Thwaite

- In the Days of Rain, Rebecca Stott’s memoir of growing up in the Plymouth Brethren in the 1960s

- Classic(s) of the Month

- Nonfiction Reviews