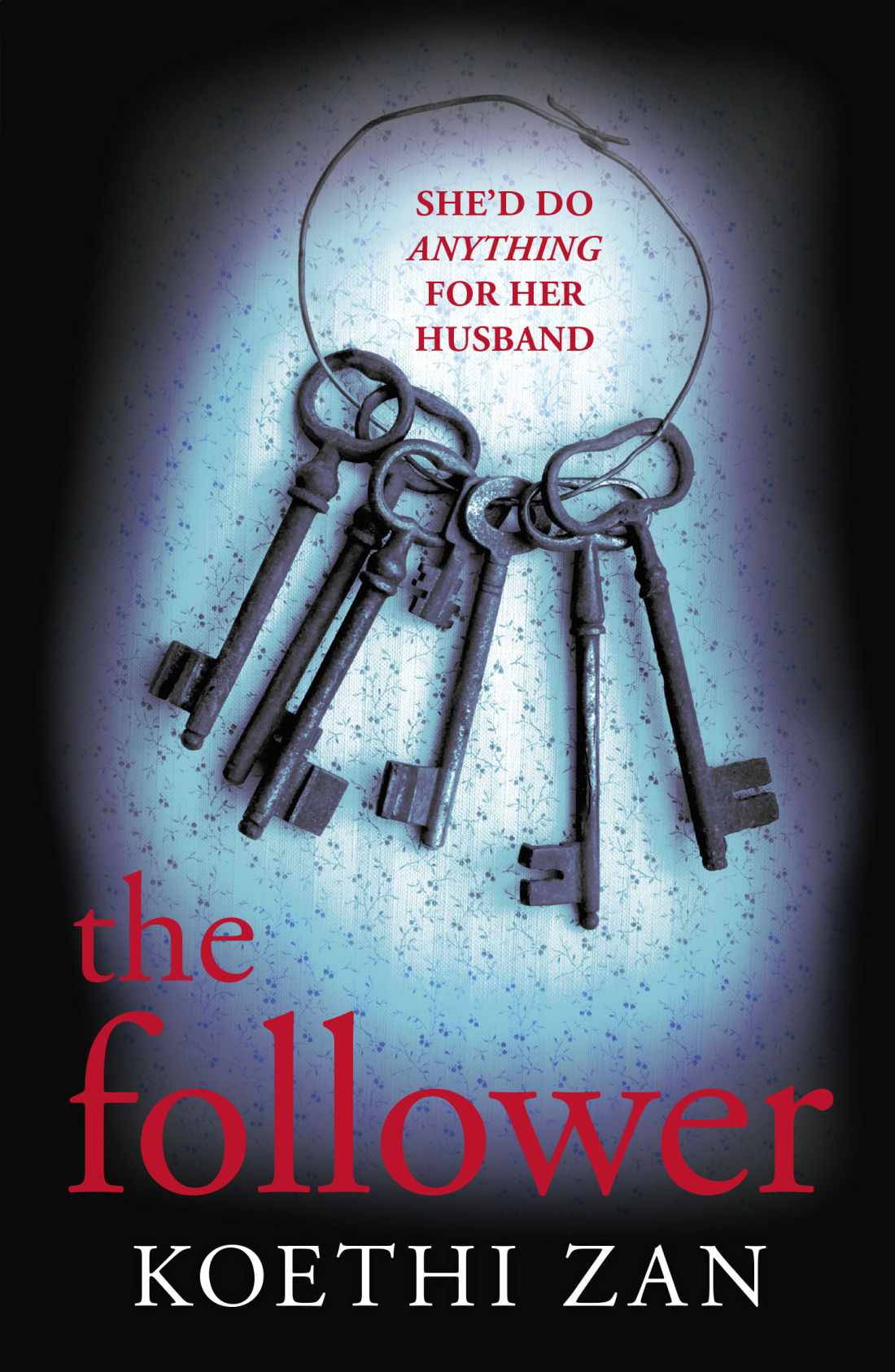

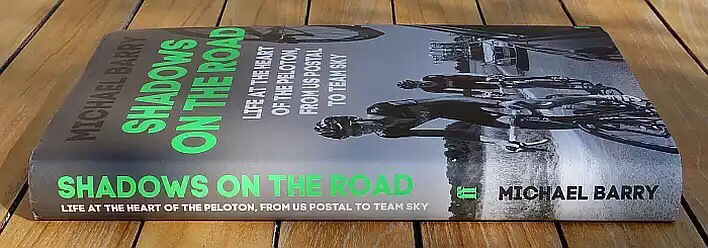

Over the last year or so I’ve read three books written by professional cyclists about the life of the pro: Michael Barry’s Shadows on the Road, David Millar’s The Racer, and Geraint Thomas’ The World of Cycling According to G. With the Vuelta about to start, it seems like a good time to mention them.

Millar and Barry, who used to train together in Girona, are now retired, Thomas is still racing, and crashed out of this year’s Tour after winning a stage in the race and wearing the leader’s yellow jersey for the first time in his career. Each of the three books has different strengths; of the three, Barry’s is probably the best, as you might guess from his previous book Le Metier, with the photographer Camille McMillan.

Business relationshipsShadows on the Road is book-ended by Barry agreeing to testify to his previous use of drugs. I’m pleased that he is candid about this, and I am also pleased that it’s not the most interesting part of the book. Barry is illuminating on how the social and business relationships of the peleton shape behaviours and attitudes within it. The pro career is short and can be ended at any time by a crash; teams win races by working together; trust is an essential part of riding with 200 others in tight groups at speeds of 45kph and more.

From the outside, they look like a band of brothers. Yet contracts are short and any rider is only one or two bad results from being dropped from the team.

CrashingAt the races, I am with my teammates twenty-four hours a day. We share rooms, eat together, race together and tavel together. There are few solitary moments. The relationships seems as close as family, but that is just an illusion. Ultimately we are are just business associates. (47-48)

All professional cyclists crash, and they crash often. It’s hard to think of another sport where everyday calamity is such an ordinary part of the routine. As Millar notes in The Racer, “When you think about the basic physics of bike racing [it] involves, on average, seventy five kilograms balanced vertically four or five feet off the ground on roughly three square inches of inflated rubber.”

His book includes a sequence of photographs by Graham Watson of the scar tissue from Millar’s worst crashes, as well as Millar’s taxonomy of the crash:

1. Mechanically induced (puncture at high speed, snapped chain, etc).

2. Slippery surface.

3. Contact with other rider in peleton leading to loss of control.

4. Individual rider taking risks and losing control or grip.

5. Loss of concentration, leading to distraction and loss of control.

6. Close proximity to anybody going through the above five.

Barry elaborates on the psychology of this over the duration of a riders’ career:

A sense of gratitudeOur lives change with each crash, and all riders can remember when a fall happens… To a spectator, who sees so many crashes, our injuries may look no more serious than a splinter or a stubbed toe, nothing more than an irritation, quickly forgotten. But e feel our injuries with the same intensity as anyone else. They hurt… With each crash we slowly lose the fearlessness of a child… [W]ithin ourselves, we are forever marked by a crash. (34-35)

One of the side effects of this is a huge sense of gratitude felt by Barry towards Sky when he crashes badly at the Tour of Qatar and they look after him properly, making sure he is operated on by a surgeon in Manchester who is familiar with cycling injuries, and accompanying him on the way there.

Cycling teams cannot afford to slow their pace. To them, an injured rider becomes a liability within a structure that is based on year-to-year sponsorship hospitals…. Most teams woud have left me in the Qatari hospital, alone, as the race rolled on. But not Sky.” (39-40)

People tend to attribute Sky’s success to the size of its operating budget, and certainly it helps, but maybe there’s more to attracting talent than salary, I thought, as I read Barry’s account here.

My wife bought me Thomas’ book to cheer me up, and to be honest I postponed reading it for a while, through fear of disappointment. I like Thomas for his refreshing candour after races as well as his undoubted toughness. But I was worried that his publisher and ghostwriter would have packaged up his ‘Cheeky Taffy’ persona at the expense of the cycling.

As it happens, The World According to G is the funniest of these three books, but the cycling still gets its fair share of the content. Pretty much any cyclist will learn from his technical accounts of climbing and descending (I’ll probably repost these separately), and the pen portraits of the people he’s ridden with (Wiggins, Froome, Cav etc) are sharp. The ‘tells’ that indicate that another rider is struggling are revealing:

‘An inch from the tyre in front’[T]he peleton can be a horrible place to be when you’re struggling. Stories fly around: this bloke’s lost his nerve. He’s a bottler. He’s gone… Because, when someone’s nerves go, you can’t miss it. The body language on the bike tells its own honest tale. They let a gap grow in front of them. They track through corners as if they are going round a fifty-pence piece.

Both Millar and Thomas come alive when they get to the technical aspects of cycling. Thomas is fascinating on the precision needed to ride the team pursuit on the track, in which he is a multiple Olympic gold medallist.

The judgments required are ridiculous, if you allow yourself to dwell on it: four of you, flat out at 63kph, each tyre an inch from the one in front… Tiny margins, huge consequences. There is no worse feeling than being in that line and knowing you are not recovering; being incapable of doing more than a half lap on your turn, knowing that the other guys are relying on you and that you are letting them down.

Millar’s description of riding a Tour de France team time trial with Wiggins, Zabriskie, and van de Velde, all strong riders, and coming second despite losing half their team along the way, is breathless. (Ryder Hesdejal was hanging on the back of the group as the fifth man needed to give them their team time.) It’s an extended piece of writing, and impossible to do justice to it in a short quote, but it says plenty about the discipline and the effort needed to ride at the top level.

The spiritual sideMillar’s book, by the way, is framed around the spine of his last season as a pro, but he uses this conceit as a way to reflect more widely on the nature of the life of the racing cyclist. As with Michael Barry’s book, he has written it himself, which I always like in a sports book. The World According to G, in contrast, is co-written with the sportswriter Tom Fordyce, though Thomas has the excuse of a full time job.

All of these three books will tell you interesting things about the nature of the pro’s life. If you only have the time or inclination to read one of them, you should read Barry’s, which gives the greatest insight into professional cycling. I’ll leave the last word with him, on his relief after leaving the peleton.

[R]iding with mates, with Dede [his wife] and alone, I realised the joy I derived on the bike as something I coud hold onto whether or not there was a number on my back… Out with friends, the finish lines are still there, as are the climbs, yet the experience is more personal and internally drven. This is the spiritual side of cycling that is lost in the business of pro racing. (225-226)

The image of Shadows on the Road is from a review at The Inner Ring, and is used with thanks. The images of The Racer and The World According to G are by Andrew Curry and are pubished here under a Creative Commons licence.

Advertisements Like this:Like Loading...