As little Peter is woken up by a ray of sunshine falling across his bed, to the morning call of  seagulls and his neighbour singing softly, we are drawn into the intimacy of his world in a town near the Baltic at the end of World War Two. Hard on the heels of this opening comes the reality of those post war days, seen through Peter’s eyes- the chaos at school, his absent mother working long shifts as a nurse, and the Russians all over the building, drunken, violent, present in Peter’s flat when he comes back from school. At last they hear that there will be a train, that they can leave, and Peter and his mother are at the station with crowds of others desperate to head west. His mother sits him down, tells him to wait and goes off to get tickets. She never returns.

seagulls and his neighbour singing softly, we are drawn into the intimacy of his world in a town near the Baltic at the end of World War Two. Hard on the heels of this opening comes the reality of those post war days, seen through Peter’s eyes- the chaos at school, his absent mother working long shifts as a nurse, and the Russians all over the building, drunken, violent, present in Peter’s flat when he comes back from school. At last they hear that there will be a train, that they can leave, and Peter and his mother are at the station with crowds of others desperate to head west. His mother sits him down, tells him to wait and goes off to get tickets. She never returns.

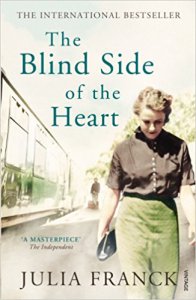

This is the devastating opening of die Mittagsfrau by Julia Franck which won the German Book Prize in 2007 and was published in English as The Blind Side of the Heart, translated by Anthea Bell. Rereading the book in English for Women in Translation Month, I’ve been struck by the force of the female perspective in the novel. The rest of the book is an attempt to explain the abandonment, to explain how any mother could be induced to abandon her child in this way and goes back to the story of Helene, Peter’s mother. Born into the middle class Würsich family, she is neglected and unloved by her mother Selma, forever mourning her four preferred boy babies who were still born. Selma’s maternal neglect is compounded by her increasing mental health problems and her vicious treatment of Helene in particular is cruel indeed. Her father is kindly but, wrapped up in adoration and concern for his beautiful but ailing wife, seems ineffectual. Neither parent considers education important for a girl and Helene, though very bright, is not allowed to study. Her rock and mainstay throughout childhood is her older sister, Marthe, and this strong female sibling bond is a theme throughout the novel.

On the death of their father, seriously wounded in World War One, Helene and her older sister, Marthe, leave their small town milieu in Bautzen for Berlin where their Aunt Fanny puts them up. Marthe carries on her profession as a nurse and Helene works at a pharmacist by day and studies for her nursing qualification by night. In fact she wants to study medicine, but she’s discouraged not only by her parents but by her male doctor boss in Bautzen who prefers to keep her as his assistant, rather than have her elevated to a position of professional parity. So on the one hand this is a milieu where women work and are not necessarily dependent on fathers or husbands- but a working world in which gender roles are very definitely circumscribed.

The novel portrays a vibrant picture of Berlin in the years leading up to the war. Aunt Fanny runs a sort of salon where artists and bohemians come together. New ideas are discussed, there is wild dancing, drinking and regular supplies of heroine and cocaine. Same sex relationships and multiple partners are permitted but the underbelly of this permissiveness is that it leaves the door wide open for male predators: Helene is constantly fending off the unwanted attentions of Aunt Fanny’s male friends. Still, she does meet and fall in love with Carl Wertheimer, their love a shared passion for poetry and philosophy as well as a physical attraction. And his Jewishness of no import in this milieu- in contrast to the Bautzen community whose shopkeepers treat Selma Würsich, also Jewish, well before the 30s, with unhelpfulness and quiet disdain. Interestingly, there is barely a mention of the growing menace of National Socialism, as if the circle around Aunt Fanny are so caught up in their pleasure seeking that they don’t see the writing on the wall. It is relatively late in the day that Helene and Martha feel antisemitism closing in on them and Helene, numbed by loss, marries Wilhelm, an engineer, for protection.

The marriage is horribly abusive: Helene is forced to stay at home and is physically beaten. By the time she gives birth to Peter, Wilhelm has left her and she is bringing Peter up as a single parent. She returns to work, her nursing skills much needed and ever more so as the war progresses. As her shifts grow longer and longer Peter is left alone and in precarious care. Now and then Helene longs to spend more time with him, to read him a story, but mostly the demands of her work take her over, allow her to lose herself and her own pain, not to think, just to do, to remove shrapnel, to bandage, to comfort the dying, to wash the dead. In the end, she is showing Peter the ‘blind side of the heart’, as her mother did to her and we can understand better her act of abandonment, convinced that anywhere he would end up would be better than with her given the inadequacy of her love.

This sad story is based on an event in Julia Franck’s own family life: she related in an interview with Zeit Online that her father was abandoned by his mother at a station in 1945 west of the Oder-Neiße Line, though she didn’t know the rest of the story, just that it had marked him deeply. When she tried to find out more about her grandmother years later after becoming a mother herself, she discovered that she’d died in 1996 near Berlin where she’d been living for decades in a small flat with her sister. She never mentioned a child. So the book was a way of giving her grandmother a story.

I was also interested in her comments on the title which I’ve been wondering about ever since reading the German when the book was first published. She says that gender determines how we interpret the title-men seeing the German title die Mittagsfrau– the midday woman- as a lover who they see at lunchtime, women seeing her as a housewife getting lunch for her kids! Both those ideas had gone through my mind- though cynical me had seen her as a sex worker rather than a lover. In fact, says Julia Franck, the title comes from a legend where the Mittagsfrau appears at midday, puts a curse on people which can only be lifted if they speak for an hour on the weaving of flax. The hour’s talking is itself a creation, a weaving of a structure- the legend showing us therefore how necessary speech is for survival. And Helene becomes more and more silent towards the end of the book- though it was her emotional detachment which struck me more.

Despite the aching sadness of the frame story, this book has much to enjoy -the characterisation of the two sisters and their relationship, the social contexts of both small town Bautzen and bohemian Berlin, the moving depiction of first love. Anthea Bell’s translation soars when she is depicting scenes of emotional intensity- the exhilaration of nightclub dancing, Helene’s first night with Carl, her fear on discovering the abandoned railway carriage in the wood at the end of the war. I recommend this book, whether in the original German or in translation to any reader interested in 20th century Germany. And particularly to those interested in a woman’s story.

Advertisements Share this: