Standalone, Dutton Books, 2011, 389 pgs.

Being the daughter of a roller coaster designer used to be an exciting, if often lonely, life. Jane’s lived all over the world and been to almost every major theme park you can think of. And even when she was isolated and friendless, she had her energetic, eccentric mother to brighten life. “Used to” being the operative phrase, though; her mother died a while back, and her father’s fallen on hard times since. That’s why she, her father, and her brother are moving into the rundown old house left to them by her maternal grandfather on Coney Island. It’s free and available, and maybe with a little luck her father can get some sort of work at one of the parks. Coney Island’s an odd place to move to, though. Not only does nobody blink an eye at the boy with tattoos covering every part of this body, not only are the bullies in the school deliberately strange, but it has history. The island’s, yes, with its fairs and parks, but Jane’s too. Her family’s. Her mother’s. And that history is in danger of being lost.

I have to say, this was not at all what I was expecting out of this book. Not that I can say I know Altebrando’s work all that well, having only read one previous novel. The Best Night of Your Pathetic Life was a piece of feel-good fluff, though: fast, fun, and engaging, but not particularly deep.

And sometimes that’s all a piece needs to make an impact. I bought this book because I’d liked the previous one I read, and I liked that book because reading it brought me back to every goofy high school movie I’d ever watched with my friends in the summer. I don’t think the novel was exactly trying to be anything else, either.

Dreamland Social Club, on the other hand, is a completely different animal. This is a book that wants to Say Something, and it has all the pros and cons that make up the territory.

Specifically, on the cons side, its sometimes gets a little bogged down trying to make its point; it’s never exactly preachy in that obnoxious, didactic way, but story rhythm is sacrificed at times in order to work into the novel’s themes. Also, the main character, Jane, is a little stiff, in a way that I’m noticing more and more often in books that want to be serious and intellectual.

It’s not that she’s awful, but she’s written to be almost unbelievably sheltered in order to differentiate her from the community she’s moving into. I can buy shy stick-in-the-mud, even if it’s not my favorite archetype, but I can’t quite accept that a girl who’s traveled all over the world and lived in major cities, both in the States and abroad, doesn’t know what “the projects” are. Again, the point being made sometimes overrides the story.

In spite of what they sound like, though, those are honestly very minor complaints. The pros very much outweigh the cons in this novel, and that is pretty much down to two things: uniqueness and nuance.

YA is a fairly political genre, but it has a tendency to keep the drama at a personal level. Most things will make nods at the huge, overarching issues society faces, like racism or sexism, but often they really only bother to skim the surface of those issues. It’s rare that I see anything that really gets down into the details, rare that a piece talks about something that isn’t an identity issue, and even rarer that the politics being talked about connect so heavily to storyline and character arc.

Dreamland Social Club isn’t only a novel about gentrification. But it is still a novel about gentrification, and most of the personal drama involved has some connection to that main theme. The characters’ hopes and dreams hang on the tension between preservation and development that’s at the center of the book, their relationships live and die by it, and even our lead’s journey to find out about her dead mother’s life has major roots in it.

Altebrando’s skillful in depicting that tension, as well. There’s no uncomplicated “corporations are evil” message, like you might expect; this is an honestly nuanced look at the issue, and nobody’s exactly a mustache twirling villain here. The people promoting development are on some level trying to make things better, though they’re ignoring the needs of the broader community and carelessly knocking down history to do so. In turn, the people looking to preserve Coney Island have their hearts in the right place, but are also sometimes desperately clinging to things that have been fading for a long time.

And most of the characters fall somewhere in between those two extremes. Babette, a character with dwarfism, is firmly on the side opposing development, but also takes offense at the idea that they should go back to the old days when her most viable career option would have been as part of a freak show. Jane herself is torn between the two; she wants to preserve Coney Island as it is in order to find out about her mother’s past, but she also wants to see the parks flourish again in order to secure her father’s job and future.

The amount of nuance Altebrando brings to this issue extends to the rest of the novel, too. The characters are all fully realized, in spite of some of them being tropes that usually set my teeth on edge. Jane’s hyper-shy innocence and the standard high school bullies in particular could have been grating, but weren’t because they all had history and development.

Every other theme the book tackles, too, has at least the potential for the same sort of depth. The plot is mostly Jane settling into her new community: making friends and finding romance, getting involved in the conflict between the born-and-bred Islanders and the company looking to build new attractions, and attempting to find out what she can about her mother’s side of the family.

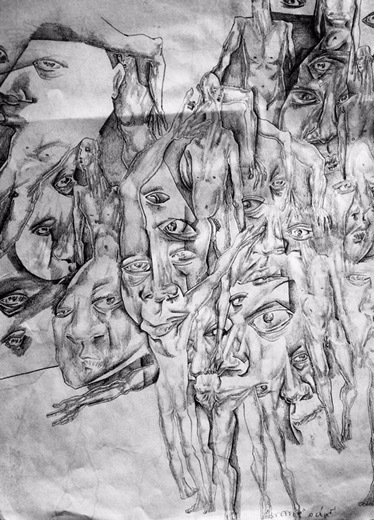

But even the very setup leads to some interesting questions. Is it wrong to be interested in the strange and the grotesque? Can “strange” be something you choose to be? How much of who we are is choice, how much is experience, and how much comes from who and what your family is? If you never knew that family, how much impact could they have on you, and can you find out who they were from outside sources? Can something that’s been lost, person or place, ever be reconstructed?

I can’t say the book fully answers any of those questions, in fact, it only ever touches on some of them. But I can see tons of little moments in it leading to good discussion. I like things that give me food for thought, even if I have to read it into bits and pieces myself. And to be frank, the ability to read nuance into a situation is something that a lot of books actively cut off.

Largely, though, this is an entertaining, interesting read, with likable characters and the ability to tackle some tough questions without being flat or annoying about it. And that’s something you don’t get every day.

Advertisements Share this: