As this past fall was approaching, my impression was that 2016 had been a pretty lousy year for movies, but by the end of the year, looking over all that I’d seen, I realized just how many excellent movies there had been.

Overall, I saw 111 movies this past year. Fifty-three of them I saw in theaters. Fifty-one were new (at least to the Twin Cities).

To my surprise, toward the beginning and end of the year, I saw Star Wars movies: Star Wars: The Force Awakens and Rogue One. Both were strong additions to the Star Wars … I can barely bring myself to say the word … franchise, with the rag-tag toughness of Rogue One being especially satisfying. Still, for all that was familiar in it, The Force Awakens packed an emotional wallop, especially in the scene with Han Solo and Kylo Ren on the bridge that recalled the confrontation between Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker in The Empire Strikes Back.

I also had the good fortune to see Chimes at Midnight in a theater. I hadn’t seen it in about thirty years, and while I’ve always had fond memories of it, time had leached the details of the film from my memory. It is among Orson Welles’ masterpieces. Speaking of masterpieces, later in the year I saw a beautiful 70mm print of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Love it or hate it, it’s a visually stunning movie and best seen on the big screen.

Since I ended up seeing so many good movies, I at least want to mention films that almost made it onto my list: Son of Saul, Knight of Cups, Aferim!, In Transit, Where to Invade Next, Wiener-Dog, and The Seventh Fire. This final film, a documentary about the life of a drug dealer and his protégé on the White Earth Indian Reservation in northern Minnesota , is probably the least-known of the group so I want to give it special notice. It is gorgeously photographed and is devastating. It’s highly recommended.

Since I ended up seeing so many good movies, I at least want to mention films that almost made it onto my list: Son of Saul, Knight of Cups, Aferim!, In Transit, Where to Invade Next, Wiener-Dog, and The Seventh Fire. This final film, a documentary about the life of a drug dealer and his protégé on the White Earth Indian Reservation in northern Minnesota , is probably the least-known of the group so I want to give it special notice. It is gorgeously photographed and is devastating. It’s highly recommended.

And last but not least, I feel I must mention that I unintentionally saw five Coen Brothers movies this past year: Hail, Caesar!; Raising Arizona; The Big Lebowski; No Country for Old Men; and Burn after Reading. I didn’t even like Burn after Reading when I first saw it in 2008, but I thought I would give it another try, in part because it is my friend Bev’s favorite Coen Brothers film. To my surprise, I found it to be quite funny. Everyone in it is great, but John Malkovich and Brad Pitt are spectacular. And No Country for Old Men is nothing short of masterful. No wonder I’ve stuck with these guys for so long.

Without further ado, here are my favorite films from last year in the order that I saw them.

Anomalisa

Anomalisa

Customer service guru Michael Stone (David Thewlis) has a problem, one that gradually becomes clear to viewers once the romance he initiates with Lisa Hesselman (Jennifer Jason Leigh) at a Cincinnati customer service conference begins to transform from something magical into some terrifyingly familiar. I’ve heard that Anomalisa is the story of a man suffering from Fregoli delusion (that constitutes a spoiler, so you might not want to look it up right now if you haven’t seen the film), but it also can be seen as a keen observation on how it is that we lose interest in life and in others. If we’re honest, it’s not life but our tedious ideas about it that become so unbearable. That the film is told with animated puppets deepens the films themes yet doesn’t get in the way of its humanity—Michael’s and Lisa’s date is fraught with vulnerability and tenderness. It’s probably Charlie Kaufman’s most touching film.

Hail, Caesar!

Hail, Caesar!

Aglow after having watched the Coen Bros.’ entertaining film set during the final years of the studio system, starring the ever-reliable Josh Brolin as Eddie Mannix, the fixer at fictional Capitol Studios loosely based on MGM’s fixer of the same name, I announced that the next genre the Coen Bros. needed to tackle was a musical. After all, Hail, Caesar! has three excellent musical numbers in it, including “No Dames,” the sharply choreographed and funny riff on something you might have seen in On the Town. Then it dawned on me: maybe Hail, Caesar! was their musical or, rather, quasi-musical. Regardless, with its casual pace and a loose plot that allows the Coens to peek in on various sound stages to show us scenes from a wealth of fictional movies being filmed, Hail, Caesar! is a paean to the magic of movies, and not very great movies at that. George Clooney, Scarlett Johansson, and Alden Ehrenreich are marvelous—Ehrenreich really shines, impressing me with, of all things, his ability to lasso something with a spaghetti noodle, which I’m guessing is a lot harder to do than it appears. So many others in the film rise to the Coens’ lunacy that it’s hard to single them out, but Ralph Fiennes has a very funny scene in which he plays a George Cuckor-like director trying to teach diction to Ehrenreich’s irredeemable cowpoke. Movie lovers will find much to enjoy here.

Happy Hour

Happy Hour

Happy Hour, my favorite movie of the year, tells the story of four close, middle-aged Japanese women whose lives, specifically whose marriages, unravel when one of them divorces her husband because she no longer loves him. Such a synopsis does not do justice to a movie that, with a running time just over five hours, has an almost novelistic heft to it. The running time allows for moments to play out deliberately, as in two bravura scenes, one detailing a workshop led by an artist who simply balances things as his art form and the other the reading of a respected up-and-coming writer, that do not so much advance the plot as deepen relationships and themes. By the end of the film, after all that we have seen and felt, one knows these women with deep sympathy. The four stars of the film won the “best actress” award at the 2015 Locarno Film Festival for their ensemble work, the only way to celebrate ensemble acting this intimate.

Right Now, Wrong Then

Right Now, Wrong Then

A charming and funny romance from prolific South Korean filmmaker Sang-soo Hong, Right Now, Wrong Then features a neat structural trick: the film is actually two films—Wrong Now, Right Then and Right Now, Wrong Then—that essentially tell the same story but with slightly different details and very different outcomes. Jae-yeong Jeong plays Ham Cheon-soo, a famous director visiting a town where a film of his is scheduled to be shown during a film festival. The day before his film screens, he sees a beautiful young woman enter the grounds of an old palace. He follows her, striking up a conversation with her. Discovering that she’s a budding painter, he asks to see her work, and she takes him to her studio. Their courtship is stumbling, drunk, and funny. In the first film, Ham is manipulative, trying desperately to win the young woman over, but not succeeding too well. In the second, film, he proves to be much more difficult to resist as he expresses his feelings simply and directly. Sang-soo deserves wider renown in the States than he currently has.

The Lobster

The Lobster

The Lobster appears to be the most divisive film I’ve seen this past year, though Arrival is a close second. The Lobster tells the story of David, a sort of schlubby everyman living in a dystopian world not that different from our own, in which society coerces single people to marry. And so David finds himself checking into a hotel at which he is expected, within forty-five days, to meet the woman he will marry or be turned into an animal—in this case, by his choice, a lobster. A resistance movement has formed by those who have fled the hotel into the surrounding woods and who have zero tolerance for romance of any kind, maiming and even killing those who show romantic inclinations toward others. In short, single people in David’s world are damned if they do, and damned if they don’t. The film’s commitment to its nightmarish illogic—and lack of any explanation or apology for it—imbues The Lobster with a sense of the uncanny similar to Kafka’s fiction.

Hell or High Water

Hell or High Water

I saw few movies this past summer—what a fetid swamp summer movies were this year; much worse than usual—but two in a row somehow featured Chris Pine. This one, however, is not a franchise, but is instead a modern western in the mode of No Country for Old Men. Coming from the pen of screenwriter Taylor Sheridan, who wrote last year’s gripping Sicario, Hell or High Water is, not surprisingly, pulpier than No Country for Old Men, not as self-consciously weighty. Also like Sicario, it is firmly located in place—in this case, West Texas. Starred Up director David Mackenzie films the landscape beautifully and elicits strong performances from Pine, Jeff Bridges (who, admittedly, is doing a variation of his Rooster Cogburn), and Ben Foster, one of the strongest actors of his generation. This movie is an excellent action film, recalling days before that meant nauseatingly endless chase and fight sequences.

Moonlight

Moonlight

Moonlight tells the coming-of-age story of a young black man from Miami named Little (Alex Hibbert) when he was a child, Chiron (Ashton Sanders) when a teenager, and Black (Trevante Rhodes) when a young man, as he struggles to find his place in a world that seems to have no need for him. His mother, a drug addict, neglects him when she’s not lashing out at him, and his apparent queerness ostracizes him from peers who struggle to find their own identities in their harsh neighborhood. Little finds some solace in Juan, a local drug dealer who finds Little hiding in one of his crack houses and who acts as a temporary father until Little realizes Juan sells crack to his mother; in Teresa, Juan’s patient and supportive girlfriend; and in his friend Kevin, with whom Chiron shares one of his rare intimate moments, one he desperately wants to recapture as a young man. Moonlight is a film shot through with beauty and the ache of wanting, needing, to fit in and to be loved, which is thwarted by the defenses thrown up to protect one from an indifferent, too often violent world. It broke my heart. Repeatedly.

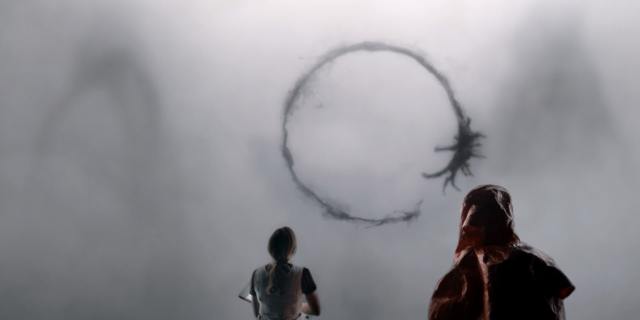

Arrival

Arrival

Amy Adams, in a remarkably heartfelt performance that should have been nominated for an Academy Award, plays linguist Louise Banks, who is brusquely invited by Army Col. Weber (Forest Whitaker) to join a team who are attempting to communicate with aliens inhabiting a spaceship hovering over a mountain valley in Montana, one of twelve ships looking like giant, charcoal Milk Duds that have appeared simultaneously around the globe. Arrival is a visually striking film that, for its rather unpromising premise, is quite moving in a story about language, cognition, parenthood, time, and a re-orientation toward death that, the film implies, will save humanity. In that way, I suppose, Arrival is a spiritual film. The movie threatens to derail in its final third-to-half, as it expands its focus beyond Dr. Banks and her work and reverts to science fiction film tropes so familiar they’re like watching wallpaper and that consign Jeremy Renner to the editing room floor. Still, as with so many of the great science fiction films, what works in this movie is so good it makes up for the missteps.

Certain Women

Certain Women

Based on stories by Maile Meloy, Certain Women tells three stories centering on three different women living in Montana (yes, Montana again). In the first, Laura Dern plays Laura, a lawyer saddled with a relentless and mentally unstable client, fastidiously played by Jared Harris in a role that I imagine would have been more fearsome in the hands of a more magnetic and less restrained actor. The second features Michelle Williams as a professional woman obsessed with building a second home in rural Montana, her obsession widening the gap between herself and her family and prodding her to talk a senile old man into selling her some historically significant stone that is piled up in his yard. The third tells the story of a shy ranch hand played by Lily Gladstone who develops a crush on a Kristen Stewart’s lawyer, who has inadvertently found herself teaching a teacher’s development class on legal issues in the classroom in a town four hours’ drive from Missoula, where she lives and works. All stories are quietly told with understated humor. Much is unspoken, and the silent, immense land in which the stories unfold is very much a presence in the drama. For me, the second segment was the least engaging, and the third, alive with the exquisite pain of unrequited love, was some of the best filmmaking I saw this year. Director Kelly Reichardt once again proves herself to be one of America’s best directors.

Manchester by the Sea

Manchester by the Sea

The premise of Manchester by the Sea is not unfamiliar: a lonely, crushed man—Lee Chandler, played by Casey Affleck in a bravura performance—whose very body language keeps the world at bay, suddenly finds himself thrust into taking care of somebody against his will, in this case, his nephew Patrick (Lucas Hedges). The film is much more than that familiar premise, though, as is slowly revealed through a series of flashbacks that, so unexpected at the beginning of the movie, seem to knock the timeline of the film askew. Through them, we eventually learn what haunts Lee, a gaping wound that will never heal, the film dramatizing how one lives in the presence of such trauma. In spite of the tragedy at its heart, director Kenneth Lonergan stays true to the comedy of everyday life, some of the film’s comic touches resounding uncomfortably in the face of unspeakable pain. With its sophisticated use of setting and its unsettling rhythms, Manchester by the Sea is an art film accessible to all in its humanity.