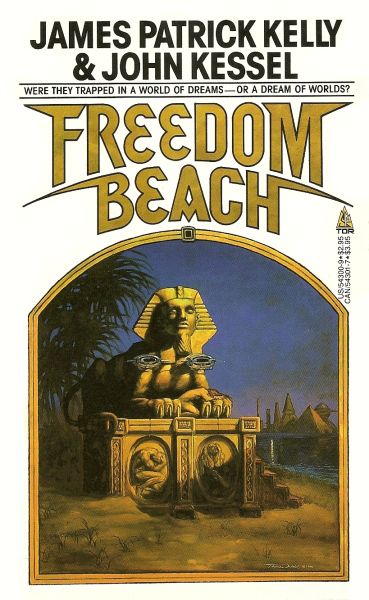

Tom Kidd cover for Tor. isfdb.org

Science fiction in the 1980’s and 1990’s developed a large preoccupation with “inner space” topics like mind-reading and dream travel. Obviously, these tropes began long before 1980, but as the size of novels ballooned in these later decades – perhaps because word processing software took over for typewriters – extended passages of dream hacking became more prominent. Through some sort of advanced technology, characters could interact with each others dreams for scores of pages.

Depending on one’s opinion of this trope, dream hacking can either enrich the readers’ understanding of the characters or merely serve to fatten manuscripts without seriously complicating the more important plot sequences. In the last couple of years, I have encountered several examples of dream hacking:

- Iris, by William Barton and M. Capobianco (1990)

- Queen of Angels, by Greg Bear (1990)

- Mindplayers, by Pat Cadigan (1987)

- Others See Us, by William Sleator (1993)

- Star of Gypsies, by Robert Silverberg (1986)

- No Enemy but Time, by Michael Bishop (1982)

Of these, the Bishop novel is the best, primarily because he combined the equally unlikely SF devices of time travel and dream hacking to create a deeply illustrative biography with an unreliable narrator. Now that I think about it, Bishop could have been expressing skepticism over the scientific claims held by (pre-DNA analysis) anthropology. The Bear, Sleator and Silverberg books are all decent but not the best works from their respective authors. I haven’t read any other Barton or Cadigan works, but the listed books did not engender much enthusiasm (although I’m almost always willing to give an author a second shot).

Freedom Beach (1985), a collaborative effort from James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel, splits most of its pages between the titular resort and extended dream sequences of the protagonist. Freedom Beach is some sort of strange purgatory where the characters are cared for, encouraged to fritter away their time, but forbidden to write anything down or make serious attempts at retaining memories. Guests, or more appropriately – patients, lead a Brave New World-type of existence, complete with a daily drug they call “communion,” nude volleyball games and abandonment of their past identities. A hidden group called “the dreamers” are in charge of this place and the patients’ therapy, interacting with them through drugs, robots and speaker-equipped statues.

We experience life in this place through the viewpoint of a struggling author named Shaun, who quickly finds cause for rebellion. The bulk of Freedom Beach therapy is to be subjected to long dream experiences that are in some way hacked by the dreamers. Shaun’s dreams draw from his memories (which are withheld while he is awake) and take radically different forms, inspired by his various creative influences:

- a collision between Goethe’s Faust and the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, called “Faustfeathers”

- a future metropolis populated by automated versions of literary figures, including Aristophanes and a relentlessly self-quoting William Shakespeare

- a Raymond Chandler-style mystery involving the life of the actual Raymond Chandler

These passages are long and detailed, and attempt to symbolize the Shaun’s struggle with the creative process. Whether you enjoy FB will depend greatly on your tolerance – or even acceptance – of these square pegs hammered into the round holes of the larger story, especially since as dreams we know nothing really happens inside of them. The dreams themselves could add up to form the story of Shaun’s difficult self-actualization, but in the days of neuroscience it’s an awful lot of fantasy of swallow.

The dream-hacking episodes are interspersed with flashback episodes from Shaun’s pre-Freedom Beach existence. In bits and pieces, we meet the secondary characters Myrna (Shaun’s ex-wife), Vic (an acquaintance with whom Myrna slept with), Murray (a college professor) and others who populate the resort as well as Shaun’s past life. Myrna emerges at the end of the book to me the more tragic figure, and her accomplishments make Shaun add up to something insignificant in comparison.

Depending on your enthusiasm for dream hacking and the writing process, readers of FB may have a more positive experience than I did. In some ways, FB is an impressive examination of how our mental life is built upon both our conscious and unconscious experiences. The dream episodes were impressive as writing exercises, but I found it difficult to understand how they were justified, especially at their length, to tell the story of a thoroughly mundane character. Like a lot of genre fiction from this time period, FB uses more to tell less, and is ultimately about the experience of being an author. 5/10.

….

NOTE: I should have also added another Silverberg book, Tom O’Bedlam, to the “dream-hacking” list. In that one, dreams are implanted into individuals across a post-holocaust world to collect them into a kind of benevolent cult. Like Freedom Beach, Tom O’Bedlam features a character (a capable therapist, instead of a failed author) that realizes fulfillment only when submitting herself to a collective will. This outcome of the individual-versus-collective conflict runs opposite to what I’ve discussed in the fiction of Jack Vance (“Sjambak”), Bishop (No Enemy but Time), and Donald Westlake (361 and especially the Parker series). Philip K. Dick’s protagonists often struggle to remain individuals also, but more often than not, they end up corrupted by institutions.

Advertisements Share this: