by Patrick Ehlers and Spencer Irwin

This article contains SPOILERS. If you haven’t read the issue yet, proceed at your own risk!

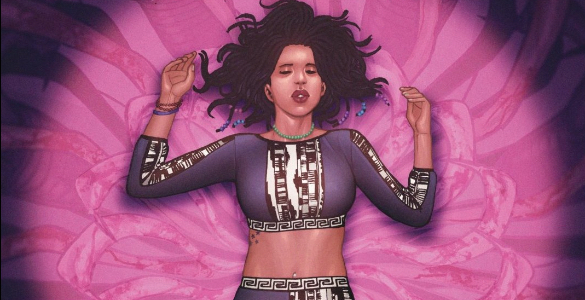

Patrick: In the first Glitterbomb series, writer Jim Zub and artist Djibril Morissette-Phan explore the late-career of actress Farrah Durante. Durante was abused by the system, sexually assaulted by her co-star, and discarded by the studio. She was emboldened by a spirit of vengeance, and ended up murdering a theater full of Hollywood’s worst scumbags in a whirlwind of intensely satisfying supernatural revenge. Mind you, it costs the character her life.

Glitterbomb: The Fame Game follows the next generation of celebrity in the form of Kaydon, Farrah’s only real friend toward the end of her life. Kaydon isn’t an actress on a TV show, she’s a personality, famous for her experience and perspective. She’s a woman of color, and at least a little bit queer, so we already know she’s able to express herself more completely than Farrah ever would have been allowed to.

I usually like to jump right into analysis for these discussion pieces, but the whole point of this issue is the decisions that Kaydon doesn’t make, and the only way to truly understand that is grapple with what happened to Farrah. Faced with the full might of the vengeance demon, and armed with a fucking gun, Kaydon has the ability to murder the people who are making her feel like shit. But she doesn’t. Instead, she turns the gun on the living embodiment of her anger, shoots it, and then simply vanishes. There’s a lot to unpack there, and I’m still wrestling with what exactly the issue values.

Zubb and Morissette-Phan still seem to be hell-bent on taking down the more traditional aspects of fame-chasing culture, as evidenced by this two-page splash montage of Kaydon trying on fancy new clothes at the mall.

There’s a kind of Los-Angeles-anonymity to the layout of this mall — it could be the 3rd Street Promenade in Santa Monica; it could the the Fig at 7th downtown; it could be at Universal Citywalk; hell, this could even be at Hollywood and Highland. Kaydon’s celebrity is neither specific, nor born out of a specific talent. Is that what makes her fame something that Kaydon is able to walk away from without being consumed by it?

Kaydon confronts this idea that she’s not something special, but a commodity in this specific moment, with startling frankness. Her scrummy-but-not-too-scummy agent lays it all out in surprisingly respectful terms, and Kaydon plasters a smile on her face that is achingly unnatural. I believe this is a turning point for Kaydon, so let’s look at the whole page.

The camera starts outside the car, keeping the agent cloaked in shadow right before Zub decides to lay out the terms of Kaydon’s celebrity. The second panel brings the reader into the car, and right behind Kaydon’s eyes — we are effectively her in this panel. The agent isn’t malicious here, in fact, he’s rather upfront about how they both stand to profit without really making compromises to Kaydon’s safety or integrity. There’s a kind of hollowness to Kaydon’s celebrity that promises neither risk nor salvation. This is a moment that would have flown past me without that silent third panel, forcing the me to process that information. Again, we’re in Kaydon’s head as she too processes what this kind of fame actually means.

So, okay: the fame is easy to walk away from because it wasn’t fulfilling in the first place. Sure, there are clothes and money and limos, but Kaydon has the integrity to immediately recognize that it’s all built on a lie. Good for Kaydon. There’s a second part here that I’m not sure what Zub and Morissett-Phan are saying about Kaydon’s queerness. In the previous issue, a possessed Kay shares a passionate kiss with her friend Martina. Kaydon recognizes that this puts Martina in danger, and duct tapes her to a kitchen chair. For her own protection. Weirder, and perhaps more damning to this issue’s point of view, is that the living embodiment of this vengeance demon strokes Kaydon’s hair and leans in for a kiss before Kaydon blows its brains out. I’m all for Kaydon rejecting the access of Hollywood (even those that come with the meager fame wave she was riding), but this issue comes dangerously close to demonizing Kaydon’s homosexuality.

I don’t know Spencer, what do you think about that? I think I may have written myself into an analysis that overshadows the rest of the issue for me. If “being gay is part of the sinful accesses of show biz” is part of this story, why should we really give a shit what else Zub and Morissett-Phan have to say? Or, am I reading too much into it and desire is desire is desire?

Spencer: You raise some interesting points about this issue’s queer subtext, Patrick, and I’ll admit that I really don’t know what to make of Kaydon’s (or Zub and Morrissette-Phan’s) treatment of Martina. Kaydon clearly fears what she might do to Martina under the influence of the vengeance monster, but simply leaving Martina’s home probably would have been sufficient — duct taping her to a chair feels needlessly cruel, especially when the previous issue established that Martina’s father is out of town for the next five days (and thus will be unable to find/free her), and especially when it’s the last we see of the character in the series. It’s a moment that leaves me at a bit of a loss, to be honest.

That said, I didn’t necessarily read Kaydon as queer, Patrick. Her kiss with Martina in issue three happened while Kaydon was under the influence of the vengeance monster, and seemed motivated by a desire to hurt Martina more than any sort of sexual desire. I don’t necessarily think the monster’s seduction of Kaydon was meant to be read as queer either (though the fact that it can be read in this context is unfortunate, as you pointed out, Patrick) — issue 2 established that this monster is currently using a pop starlet as its host, which makes it 3 for 3 on choosing female hosts, likely because they’re the most harmed by the culture of Hollywood. I wasn’t really even thinking of the creature as a woman, but as a walking metaphor — a living vessel of vengeance against a corrupt, sexist culture. The desire for revenge is what’s tempting Kaydon, not anything sexual — and that offer probably wouldn’t be as tempting if the creature took the form of a man, given that they’re ones hurting Kaydon, Farrah, and so many other women so many other times. Kaydon would be more likely to trust or be tempted to take vengeance by a woman, I think.

On that note, I don’t think that Kaydon’s big choice is walking away from fame. The creature doesn’t really give Kaydon the option to keep pursing her newfound infamy — either she gives into it, or she slays it. Either way, she couldn’t remain famous, at least not the way she’d like to. The choice is basically taken out of her hand. By killing the creature, what Kaydon is rejecting is the desire for vengeance.

Here the creature is describing Hollywood and media figures who feed off the misery of others, but it could just as easily be talking about itself. The creature is initially attracted to Kaydon because of her misery, and quite literally feeds off of it in the same way it accuses the media of feeding off misery. It talks of the media being an endless cycle of manipulation, but the creature itself feeds into that cycle, perpetuating an infinite loop of misery. This form of sensational media can’t exist without the misery of others, but the creature can’t exist without the media causing misery either; their relationship is practically symbiotic.

Kaydon has seen first-hand the misery the creature brings. She saw what it tried to make her do to Martina. She saw what it did to Farrah. The creature promises catharsis, but Kayden knows that its catharsis inevitably brings pain as well. How could she not reject it, kill it? Actually, given the symbiotic relationship between the creature and Hollywood/the media/fame in general, Kayden realizing that the monster only brings pain probably means that she’s realized the same about fame. It’s why her only real choice was to drop off the face of the Earth altogether, to find a mundane life of anonymity. The only way to break the cycle was to remove herself from it entirely.

Of course, Kaydon nearly removes herself in the most permanent way possible.

Does Kaydon nearly kill herself because of the guilt of taking a life? Because she can’t bear all she’s lost? Because fame has left her empty? We can’t be entirely sure, but what’s clear is that her decision not to go through with it is as clear a rejection of the vengeance monster as killing the creature itself. She won’t let its evil spread anymore, even to herself. Yet, Kaydon’s murder of the creature is a form of revenge on its own, revenge for the death of her friend Farrah. There’s an irony there, to be sure, but even this can be seen as being born of a desire to stop the creature from inflicting any more misery on anyone else. Maybe she breaks the cycle less by killing the monster outright, but more by leaving after she does instead of sticking around and taking credit for her actions.

So yeah, there’s definitely ways to bring this all back around to fame, but for the most part, that’s still Glitterbomb: The Fame Game‘s biggest weakness: it might just be a little too much about the creature and not enough about the celebrity culture it’s supposed to be skewing. This series’ critique of fame just doesn’t feel as scathing as its predecessor’s, the injustices Kaydon and company face this time around seeming much more mild than what Farrah faced — and unlike Farrah, Kaydon walked into these situations, and continued to, completely willingly and mostly understanding what they entailed. Fame is mostly reduced to subtext when it comes to the conclusion, where, as I’ve laid out, Kaydon’s final decisions are more a rejection of the creature itself and the vengeance it stands for than fame or celebrity. I certainly wouldn’t say that Glitterbomb gets caught up in mythology or world-building — the creature’s origins remain blessedly unexplored — but it does let its supernatural star muddy the parable it’s trying to tell. The first volume of Glitterbomb was built around obvious pain and outrage — The Fame Game is a bit more subtle and complex with its message, for better or for worse.

For a complete list of what we’re reading, head on over to our Pull List page. Whenever possible, buy your comics from your local mom and pop comic bookstore. If you want to rock digital copies, head on over to Comixology and download issues there. There’s no need to pirate, right?

Advertisements Share this: