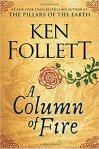

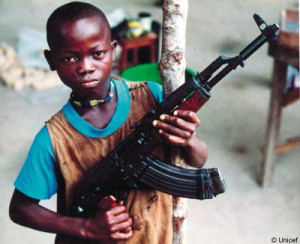

One of the most haunting images of war around the globe is that of children holding semi-automatic weapons. In the United States, these images shock a belief system. Children should be in nurturing home environments, enjoying the company of friends after school, taking clarinet lessons, playing softball. They should be allowed to be kids and dream.

Enlisting children as soldiers permits conflict to continue long after a desperate faction’s supply of adult combatants has been exhausted. The global costs are astronomical. According to http://www.child-soldiers.org/ Child Soldiers International, many children who join armed groups volunteer. Their reasons may be any of the following:

- Survival

- Poverty and lack of access to education or work (thus the need for income)

- Desire for power, status, and social recognition

- Pressure from family or peers

- Desire to honor a family tradition

- Desire to escape domestic violence (and for girls an arranged marriage)

Americans convince themselves that such extreme measures happen elsewhere, in distant lands. But historically America has inherited a legacy of children in the military that’s just as horrific as modern conflicts with child soldiers. There were drummer boys on battlefields, sailor boys on navy ships, and ragged children traveling with armies as camp followers. Did these children escape the bullets and bayonets? No.

Children don’t escape war.

Two years into the American War of Independence, the fight was going poorly for the Continentals. The Congress was determined to raise an army of eighty-eight infantry regiments. Joseph Moseley answered Congress’s recruitment call in March 1777 and enlisted as a Continental private in the newly made 14th Virginia Regiment. Joseph had just turned twelve years old.

In the 14th Virginia, Private Joseph Moseley wore a uniform, carried a firearm that was probably taller than he was, and was paid six and two-thirds dollars per month. His two teenage brothers were also in the regiment. Left behind at home were a mother widowed for eight years and a brother and sister, both younger than ten years old.

Joseph was discharged in February 1778, just after his thirteenth birthday. During his year of service, his regiment participated in major battles—Brandywine and Germantown—that were losses for the Continentals. The regiment also endured winter camp at Valley Forge. Joseph saw morale in the Continental Army at its lowest point, before the French, the Spanish, the Dutch, and Baron von Steuben offered their aid and changed the course of the war.

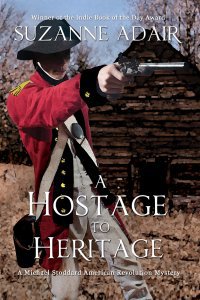

Joseph Moseley was my great, great, great-grandfather. Until I conducted research for my membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution, my family thought that Joseph had joined a militia unit as an older teen at the end of the war and spent a year performing low-profile duties for the men: gathering firewood, cleaning weapons, digging latrines. We were stunned by the truth of a twelve-year-old in uniform who looked across battlefields at hundreds of disciplined redcoats with fixed bayonets. The third book of my Michael Stoddard American Revolution mystery series, A Hostage to Heritage, includes a sub-plot about child soldiers. Joseph has earned his spot on the Acknowledgements page.

My ancestor’s reasons for enlisting are found in the bulleted list earlier in this essay, echoes of the reasons why children enlist today, a disconcerting history lesson. Joseph and countless other children picked up the firearms of dead men and continued the fight for the Continental Army. In doing so, they extended armed conflict for six years. And since our “Revolutionary War” was but one theater of a world war, the negative impact on the global economy was staggering.

Nations and factions have been using child soldiers for thousands of years. The effect on the children is obvious. Joseph and those who fought at his side had no childhood. At the least, they suffered from some degree of post-traumatic stress disorder for the rest of their lives, even if they volunteered for duty and were discharged with no physical injuries.

Today’s child soldiers in Africa, Asia, South America, and the Middle East are all of humanity’s casualties. They show us the costs of war, no matter how hard we try to look elsewhere.

Is there a child soldier among your ancestors? What do you think it will take to finally put an end to this horrific practice?

*****

Bio:

Award-winning novelist Suzanne Adair is a Florida native who lives in North Carolina. Her mysteries transport readers to the Southern theater of the American Revolution, where she brings historic towns, battles, and people to life. She fuels her creativity with Revolutionary War reenacting and visits to historic sites. When she’s not writing, she enjoys cooking, dancing, and hiking.

Social media links:

Web site and blog: http://www.SuzanneAdair.net/

Newsletter: http://tinyletter.com/Suzanne-Adair-News/

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/Suzanne.Adair.Author/

Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/Suzanne_Adair/

Book description:

A boy kidnapped for ransom. And a madman who didn’t bargain on Michael Stoddard’s tenacity.

Spring 1781. The American Revolution enters its seventh grueling year. In Wilmington, North Carolina, redcoat investigator Lieutenant Michael Stoddard expects to round up two miscreants before Lord Cornwallis’s army arrives for supplies. But his quarries’ trail crosses with that of a criminal who has abducted a high-profile English heir. Michael’s efforts to track down the boy plunge him into a twilight of terror from radical insurrectionists, whiskey smugglers, and snarled secrets out of his own past in Yorkshire.

Universal buy link: https://books2read.com/u/38DAYw

Share this: