Cover by Mark Buckingham & Steve Buccellato

“Ain’t It a Drag?”

Writer: Tom King

Artists: Kevin Eastman & Freddie Williams II

Letterer: Clem Robins

Editors: Brittany Holzherr & Dan DiDio

I’ve heard Tom King’s name a lot lately, in connection with projects like The Vision and Mister Miracle; according to one acquaintance, King is the best writer currently active in comics. But I hadn’t gotten around to reading much of his work yet. I don’t read everything, so until reading “Ain’t It a Drag?” in Kamandi Challenge no. 9, I knew King mainly by his reputation. On the basis of this one story, I have become a believer.

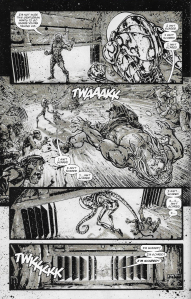

The plot of “Ain’t It a Drag?” is simple, almost schematically so, and is a departure in style and format from the previous chapters of this ongoing serial. The detailed, monochromatic art by Kevin Eastman (who has plenty of experience with talking animals as co-creator of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles) and Freddie Williams II combines with King’s dialogue to create a story that unfolds elegantly, like a fable. In broad strokes it could take place anywhere or to almost any character, but in its details it shows off what makes Kamandi and his world distinctive.

Kamandi awakens in an enclosed, cave-like room with a number of other people, or rather the anthropomorphized animals who are Earth A.D.’s primary inhabitants. Kamandi has only a vague memory of the sea serpent that menaced him at the end of last issue, but at some point he was captured and taken to this place.

Periodically, over a period of months, a door opens and an alien-looking robot (or something) enters, grabbing one inmate and dragging them away: where or to what fate is unknown, but everyone has varying opinions. Herbert, a friendly elephant, is optimistic and describes everything as “awesome.” Maybe the visitor is taking people away to somewhere awesome, and it’s so great nobody wants to come back? Could that be why no one has returned to describe it?

Other animals react in their own way, in fear or acceptance. A mother kangaroo pleads “Not my baby!” every time the dragging begins, until she is herself taken. A small bird spends time writing a story about the cave and what might lie beyond it. Kamandi, for his part, occupies himself building his strength and making plans to attack the robot, each time failing to even slow it down. Ultimately, after everyone else is gone, he too is taken, and the cave is empty except for the slab-like bench that was the cave’s only furniture, now clearly a symbolic coffin.

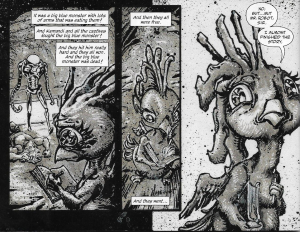

The most obvious interpretation of this story is to regard the door as death, the fate to which all of us are eventually dragged and from which no one has returned to describe the experience. No amount of strength, preparation, or pleading can put it off when it’s your time, but it is ultimately part of the rhythm of life, a fact to be accepted as best one can. Herbert’s faith in something “awesome” beyond the door is a comforting religious belief. Others live in denial, escaping into nostalgia or fantasy, or maintaining a “stiff upper lip.” One inmate, a moss-covered turtle, has seen generations come and go in the cave, and decides that it is his time; he steps forward to meet his fate, only to be ignored (although he is later gone, so I guess he eventually was taken). How much easier it must be to make one’s peace with the end when friends and family are already gone, no works left undone.

Kamandi’s single-minded attempts to defeat the intruder, to escape from the cave, to defend the other inmates, are both one common reaction taken to extremes and a perfectly apt behavior we would expect from an action hero. In his more conventional adventures, Kamandi is perpetually escaping and throwing off impediments to his freedom. He is often described as “pugnacious,” and here we see what that really means in the face of impossible odds: fighting until the last, refusing to submit. “All we know about what they’re going to do is . . . what they’ve done,” Kamandi tells Herbert, explaining why he fights so hard. “And those kinds of people, who do this . . . they don’t take you someplace nice or awesome. They just don’t.”

Of course, this is still part of an ongoing narrative: Kamandi refers to his past, relating all of the crazy stuff the previous authors have put him through, and while the ending is barely a cliffhanger, we can trust that Kamandi didn’t literally die at the end of the story. The metaphor only goes so far. It’s not a coincidence, I am sure, that the characters’ place of imprisonment is a cave, the Platonic symbol of an illusory reality. The various expressions of fear, regret, pride, and acceptance the inmates display are just coping strategies for a situation over which they have no power except in their own attitude. As easy as it may be for prisoners to identify the cell as their entire world, there is clearly something beyond the door in this story, and I have faith that the next authors will give Kamandi a chance to escape.

But that’s the problem with faith, isn’t it? By definition it is an expectation without a concrete foundation. I imagine that readers in 1978 had faith that Kamandi would continue to be published after issue no. 59, but the industry-wide collapse that led to the “DC Implosion” and the book’s cancellation put an end to that, much more quickly than anyone could have expected. I have faith that I’ll be around in October to read Kamandi Challenge no. 10, but an errant nuclear missile, or a careless driver, or a dislodged blood clot in the wrong place could cut off that possibility. If that happens, then Kamandi’s story will have ended here, at least as far as I’m concerned.

That belief that the story, both in the sense of a constructed narrative and in the sense of life itself, will continue is an essential assumption, however. Without it, only despair and inertia are possible. Kamandi, in the dialogue of this story, makes an observation that gets to the essence of storytelling, particularly of the serial variety: “It all just leads to the brink of something horrible. And over that brink, you go over. And you’re back to . . . everything. . . . And that goes on . . . it just keeps going on.” Kamandi says these words in a moment of existential despair, overwhelmed by the flood of oncoming events that is perpetually his life. Herbert the elephant, ever the optimist, replies, “Yes, exactly. I bet that’s exactly right. And isn’t that awesome?”

“Ain’t It a Drag?” is preceded by a quotation from Blaise Pascal (“I know not whence I came. I know not whither I go.”) and ends with one from Jack Kirby, one that contextualizes Herbert’s search for awesomeness and reinforces the notion that this shadow play is concerned primarily with mortality, with one’s place in the universe and the unknowability of it all. Kirby, who would have turned 100 in August, was most at home balancing the intimacy of character with the sprawling canvas of the cosmos, microcosm and macrocosm, and he rarely favored subtlety. Humanity, to Kirby, is no less powerful and dramatic than the greatest forces in the universe, because those same forces are at home in the hearts and souls of men and women. If King, Eastman, and Williams have distilled the essence of serialized storytelling and of the character Kamandi, they have also placed it in a context befitting the master world-builder and “King of Comics” himself, and touched on the power from which Kirby so liberally drew. In placing Kamandi in a narrative as conceptually audacious and formally inventive as those Kirby himself favored, they have created one of the most powerful tributes to him that I have yet seen in this, his centenary year.

Advertisements Share this: