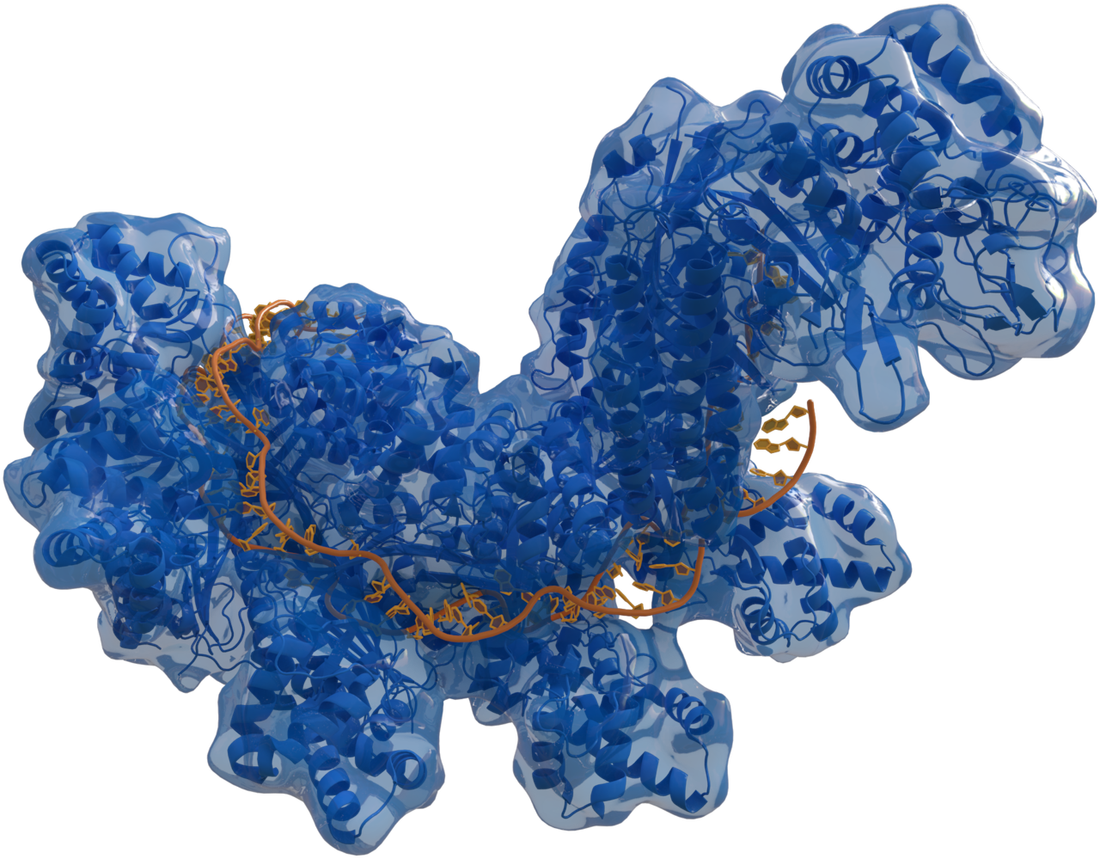

Type-I CRISPR RNA-guided surveillance complex (Cas, blue) bound to a ssDNA target (orange). By Thomas Splettstoesser

Type-I CRISPR RNA-guided surveillance complex (Cas, blue) bound to a ssDNA target (orange). By Thomas Splettstoesser

AbstractThe possibility of an engineered pandemic is one of the more terrifying new risks of the 21st Century. As technology lowers thresholds for developing bioweapons, even individuals with relatively ordinary knowledge and budgets could become responsible for extraordinary threats. Although several real-life bioterror incidents are known, no large-scale pandemic has yet occurred as a direct result of terrorism. Fiction, however, offers detailed scenarios of such events. Writers of these narratives find themselves at the intersection of modern science and deep literary tradition of pandemic narratives, originating with biblical accounts of plagues. This article examines portraits of ‘lone wolf’ bioterrorists in several contemporary fictional sources, focusing on how writers draw on counterterrorism discourse, particularly in their attempts to psychologically model the perpertrators. It flags up the dangers of a truncated speculative space, and concludes with a discussion of impacts these imaginaries might have, through influencing how emergent bioterror threats are perceived by scientists, policymakers, and the public.

Dr. Polina Levontin, Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London

Dr. Joseph Lindsay Walton, Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, University of Edinburgh

Prof. John Mumford, Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London

Dr. Nasir Warfa, Centre for Trauma, Asylum and Refugees & Department for Psychosocial and Psychoanalytic Studies, University of Essex

IntroductionApocalypse, long a staple of fiction, has recently emerged as an object of scientific enquiry. In 2012, the University of Cambridge established a research centre, the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, devoted to understanding the ways in which the world might end.

For this relatively young field, consensus on methodology, terminology and classification of risks has yet to emerge. However, an existential risk is a widely adopted scientific term for any plausible cause of an apocalypse, defined as a possible event whose consequence is an irreversible destruction of humanity (Rees 2003). A lesser category, mere global catastrophic risk, refers to hazards whose potential destructive impacts are global in scope, but fall short of wiping out humanity (Bostrom and Cirkovic 2008).

Most risks examined by researchers have been mirrored in fiction. Conversely, the apocalyptic themes so familiar from literature and film now recur as chapter headings in academic publications (Bostrom and Circkovic 2008). Many of these cataclysms are loosely ahistorical – supervolcanoes, meteor impacts – in the sense that they occur independently of human activities (although human activities clearly have bearing on their outcomes). Other risks, however, have been introduced by science in the 21st century. Self-replicating nanotechnology could run amok and, in the direst of scenarios, consume all life on the planet. AI systems could eliminate or subjugate humans, or more insidiously, could render essential features of humanity obsolete. A physics experiment could rupture space-time.

The cases thought most likely to occur, however, are hazards stemming from the biological sciences (Bleek 2011). A recent speech by Bill Gates focused on malicious bio‑hacking; the speech was widely reported, with headlines such as, “Bill Gates: Bioterrorism could kill more than nuclear war — but no one is ready to deal with it” (from the Washington Post (2017) on February 18). Sensational as such headlines may sound, such fears are not irrational. New tools such as CRISPR, designed to make editing DNA cheap and easy, could democratise the ability to engineer life. As a by-product of scientific progress, synthetic biology represents a massive empowerment program, potentially putting the means to engineer biological apocalypse – intentionally or not – within reach of millions.

This is historically unprecedented. Armed with only a sharp object, a single person can likely kill only a few victims. Armed with a gun or a vehicle, perhaps dozens. Armed with a nuclear device such as a dirty bomb, tens of thousands. But an individual armed with an engineered biological weapon might in theory kill millions (Nouri and Chyba 2008). Assessing potential damage from an individual acting alone, throughout history, Ackerman and Pinson (2014) quote John Robb (2008, 8) from his “Brave New War: The Next Stage of Terrorism and the End of Globalization”: ‘over time … as the leverage provided by technology increases, this threshold will finally reach its culmination – with the ability of one man to declare war on the world and win’. Experts on biosecurity are predicting that individuals or small groups with neither exceptional skills nor exorbitant budgets would be able to deploy bioweapons capable of sparking a devastating global pandemic (Nouri and Chyba 2008).

Psychology of the lone wolf bioterroristIndividuals or small insular groups who are not explicitly backed in terms of finance or skills by organisations are often termed ‘lone wolves’ (Ackerman and Pinson 2014). We adopt this terminology, while acknowledging that both its application and implications are not unproblematic.[1] The threat posed by lone wolf bioterrorists has been in the public consciousness since at least the anthrax scare of 2001, sustained by articles such as “The Danger of the Lone‑Wolf Terrorist” in Time magazine from 27 February, 2013. In 2001, Bruce Ivins, a microbiologist working in a government laboratory, deliberately released anthrax, killing five people. This, at any rate, was the conclusion of the Justice Department after an almost decade‑long investigation. No charges were ever filed, and Ivins himself committed suicide in 2008; some uncertainty persists about whether he was really responsible for the attack, and about the role the pressures of investigation played in his suicide (cf. Doherty 2013). Ivins was characterised as anti-social, mentally unstable, and harbouring personal grievances accompanied by a political agenda (D’Arcangelis 2015). A 2011 report by a panel of psychiatrists went further, suggesting Ivins was homicidal in the last weeks of his life, and could have perpetrated worse attacks, were he not committed involuntarily to psychiatric care. This report also notes a traumatic childhood, and an ability to hide his pathological side from the closest of colleagues, as reported by Scott Shane (2011) in the New York Times on March 23.

In research on the motivation of terrorists, mental health has been a persistent theme. Different research groups have reached diametrically opposed conclusions, ranging from characterising all such actors as sufferers of mental illness, to postulating that, as a population, terrorists are less likely to exhibit mental health problems (Corner and Gill 2014). What does emerge consistently are differences between lone wolf terrorists and those that act as a part of larger groups or networks (Corner and Gill 2014). Reviewing the evidence, Corner and Gill (2014) find that lone wolf terrorists have much higher prevalence of mental illness than terrorists acting in larger groups. The relationship between mental health and crime of any kind remains, however, extremely complex, both ethically and epistemologically. Ethically, both research and fiction risk disseminating harmful and sensationalist stereotypes about the violence or criminality of the mentally unwell. Epistemologically, it is difficult to assess what role mental health factors play in determining which acts of violence are identified as crimes and/or terror in the first place, and in determining how perpetrators become available as subjects of formal psychiatric scrutiny.

Furthermore, setting aside any possible psychological similarities among lone wolf terrorists, the mechanisms by which they have been drawn to terror are patently diverse. A comparison of two different 2013 terror attacks illustrates this point fairly well. Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale, responsible for Fusilier Lee Rigby’s killing in Woolwich, were born and raised in the UK, and socialised within a British way of life. They started to disengage from secular/liberal UK society following exposure to radical preachers. The theories and controversies around radicalisation thus provide a useful framework for understanding the motivations of the Woolwich attackers. It has further been claimed that Michael Adebolajo had been under regular pressure from British intelligence services, and that he underwent torture, including sexual assault, at the hands of Kenyan security forces some months before the attack (Nusaybah 2014). Quite different psychological processes of marginalisation and separation prove more effective in explaining the motivations of the Boston Marathon bombers, Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev. As recent immigrants from Russia, these two brothers were unable to integrate effectively into the mainstream of American society. They maintained divided role identities between their new and old cultures, while also becoming marginalised from their original community. For example, family and community disowned the older brother, Tamerlan, long before the attack.

In short, attempts to build psychological frameworks to predict lone wolf bioterrorism face obstacles that are serious and perhaps often insuperable. In the future, lone wolf bioterrorists may be motivated by a wide range of ideas and ideologies, including those which have not yet come to wide notice. Clearly, when dealing with the emergent existential risks of bioterrorism, psychiatric research on lone wolf terrorists cannot be discounted. However, there is no single theory, psychiatric or otherwise, that can be reliably called upon to predict lone wolf bioterrorism.

Narrative approaches to existential and global catastrophic riskAre there other options for exploring the psychology of emergent bioterror threats? We may lack a reliable formal framework to explain and predict such threats. But this deficiency does not mean that researchers can neglect the motivational dimension of bioterror. Rather, it points to the need for a pluralist approach, incorporating traditional and emergent science methodologies, as well as ‘soft’ methodologies of the humanities.

Because such scenarios are still hypothetical, fiction is one of the few places where we can observe them unfold. Imaginative portrayals of bioterror can help to broaden our conception of the forms that such acts could take. If portrayals of where, when, why, and how bioterror attacks could occur can usefully inform counterterrorist policy, then fiction may function as a kind of preventative diegetic prototyping, a set of self-negating prophecies, or a source of what economic sociologist Donald MacKenzie calls ‘Barnesian counterperformativity’ (MacKenzie 2006, 19). In other words, the production and distribution of models of the future may help to reshape the future, so that it does not conform to those models. Alternatively, bioterror narratives may increase the probability of an actual event. Yet another reason to take such narratives seriously is their capacity to function as a kind of generative prototyping, influencing the ways in which bioterror and counterterrorism are performed in reality.

This points to another reason why security scientists should take fictional portrayals of bioterror into account: if they do not do so deliberately, they may do so unconsciously and uncritically. Scientists, like writers, may find themselves constructing hypothetical scenarios, and may be influenced by fictional representations. In one recent study, scientists tasked with assessing biosecurity threats described the need to combine ‘science-based discourse about “plant pathogens’ and pests”’ with subjective insights into the mind of the perpetrator as ‘paradoxical’ (Suffert 2017, 33). This is a paradox that must nevertheless be confronted, and in so doing, security experts contemplate questions similar to what a writer would ask themselves in drafting characters and plotting (Suffert 2017, 33): ‘Who are they, why are they acting, what are their capacities and knowledge?’ To answer these questions, participants in one risk assessment exercise adopted the role of an imagined perpetrator:

[…] they defined a tangible target and selected the most appropriate pest of pathogen from a list of candidate organisms. Based on this, the risk analysts wrote a brief scenario describing the hypothetical agroterrorist attack and its expected consequences.

The three sections of the scenario: ‘Synopsis’ (mode of operation and expected consequences), ‘Justification’ (geopolitical context and perpetrator motivations), and ‘Feasibility’ (perpetrator capacity to succeed and technical constraints) were substantiated […] (Mumford et al 2017, 130)

When scientists engage in what are effectively creative writing exercises, and writers consult scientific sources in order to create scientifically plausible fictional plots, it becomes impossible to sharply separate the scientific discourse from a discourse about the imaginary, and hence about the literary. Both fictional works and scientific assessments on biosecurity are influenced not just by the real terrorist precedents but by the trajectory of the pandemic narrative.

In the remainder of this article, we explore several modern and contemporary novels featuring lone wolf bioterrorists. These texts derive from both a rich literary history of portraying pandemics and the scientific context of bioterrorism. Fictional examples of lone wolf bioterrorism are analysed from both directions: from a literary tradition of pandemic narratives, and from a biosecurity perspective.

A trajectory of pandemic narrativeIn 50 Ways the World Could End science journalist Alok Jha presents an exhaustive list of scenarios that have a chance of bringing ultimate destruction to humanity. Global pandemic is the first one he tackles. The distinguished astrophysicist Martin Rees, in a similar assessment, Our Final Century, makes a distinction between pre-millennium epidemics, which were mostly caused by naturally occurring pathogens (with exceptions such as a 1979 release of anthrax near a bioweapons facility in Siberia, experiments during WWII by the Nazis and by Japanese scientists), and the risk of engineered pandemics post-2000. That no such outbreak has occurred so far is a reflection of good fortune, the functionality of counterterrorism measures, and the still relatively high skill/funding thresholds: terrorists have made various attempts to deploy biological weapons, but they have failed. The cult organisation Aum Shinrikyo included members who obtained PhDs in virology, and had plans to obtain Ebola and Anthrax, and use genetic engineering to develop bioweapons based on those (Bleek 2011). A computer seized from a Syrian rebel group allegedly contained guidance on turning a bubonic plague into a bioweapon (Suffert 2017, 41).

Not without cause, then, did bioterror establish itself in the public imagination, fuelling demand for the genre. Writers have responded by creating narratives that mix the biological thriller genre with terrorism. Culture theorist Priscilla Wald summarises this trend as a turn in an already established genre:

Towards the end of the twentieth century, a noticeable shift in biohorror stories marked a heightening attention to terrorism, especially in the United States: anxieties about bioterror in particular increasingly inflected subgenre. (Wald 2012, 100)

Divinely-ordained and ‘Natural’ pandemicsWithin apocalypse narratives, plague already features in some of the earliest written examples, such as the biblical book of Daniel (Rowland 1995). Apocalypse by plague takes the literary form of a novel with Mary Shelley’s The Last Man, published in 1826, not long after Malthus’s 1798 Essay on Population, and at a moment when the English novel itself is still relatively new. (Indeed, Daniel Dafoe’s 1772 A Journal of the Plague Year, which may be considered a prototypical English novel, is a fictionalised but painstakingly verisimilitudinous account of the 1665 Great Plague).

In these pre-20th Century works, human actions are already implicated in apocalyptic pandemics. While ‘Nature’ may be the direct source of pandemic, it is not strictly separable from human activity, and humans are to blame at the very least for creating conditions for pathogens to arise and spread. Human hubris, and unpredictable interactions between humans and Nature – whether Nature is figured as divine, or as the unpredictable effects of complex systems – are themes that can be traced right through to contemporary narratives. Trade, travel and conquest help the plague to spread in The Last Man, just as overpopulation leads to a crash in Stewart’s Earth Abides (1949), and globalisation makes it impossible to contain a pandemic in Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven (2014).

In such texts, pandemics are often presented as Nature’s reaction to a species whose behaviour invites extinction. Ideas may be borrowed from ecological science. Habitat destruction through wars is highlighted as a cause of pandemics in Kurt Vonnegut’s Galapagos (1985) and Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954). In these two examples, apocalyptic pandemics are caused by bacteria, which cause infertility in Galapagos and a conversion to a new (vampire-like) species in I Am Legend. ‘When anything gets too numerous it’s likely to get hit by some plague’, offers the main character of Earth Abides, a natural scientist (Stewart 1969 [1949], 125). These novels illustrate the premise that humans are subject to the same laws of nature as any other species: by exceeding carrying capacity, by forming a single contiguous population through globalisation, by habitat destruction, humans increase our own vulnerability to a population collapse.

State and corporate sponsored pandemicsIn the earliest representations of conspicuously unnatural pandemics, those that have been engineered, the culprits are typically faceless governmental programs. One of the earliest examples where synthetic biology is implicated in an apocalyptic narrative is The Day of the Triffids by John Wyndham, appearing in 1951. In this so-called ‘cosy catastrophe’, government scientists apparently arm orbiting satellites with engineered viruses:

Great as was the public concern which followed the triumphant announcement of the first nation to establish a satellite weapon satisfactorily, a still greater concern was felt over the failure of others to make any announcement at all, even when they were known to have had similar successes. It was by no means pleasant to realize that there was an unknown number of menaces up there over your head, quietly circling and circling until someone should arrange for them to drop – and that there was nothing to be done about them. Still, life has to go on-and novelty is a wonderfully short-lived thing. One became used to the idea perforce. From time to time there would be a panicky flare-up of expostulation when reports circulated that as well as satellites with atomic heads there were others with such things as crop diseases, cattle diseases, radioactive dusts, viruses, and infections not only of familiar kinds but brand-new sorts recently thought up in laboratories, all floating around up there. Whether such uncertain and potentially backfiring weapons had actually been placed is hard to say. But then the limits of folly itself – particularly of folly with fear on its heels – are not easy to define, either. A virulent organism, unstable enough to become harmless in the course of a few days (and who is to say that such could not be bred?), could be considered to have strategic uses if dropped in suitable spots.

(Wyndham [1951] 1999, 20)

Meanwhile, down on the ground, various corporations engineer motile, stinger-equipped, carnivorous plants: the titular triffids. Wyndham’s novel is notable for bringing together two speculative threats, and extrapolating their interaction. Only after a ‘meteor shower’ (which is eventually hinted to have been a satellite weapon system, perhaps activated accidentally) leaves most of humanity blind, do the triffids begin to show their true adaptability and intelligence. In this satirical indictment of Cold War logic and corporate greed, the emergent cataclysm leaves just enough survivors for humanity’s second chance.

Megarich mastermindsWithin pandemic narratives, figures who near the profile of a lone wolf bioterrorist with limited (but sufficient) skills and resources may instead be absorbed into an ‘evil genius’ archetype. This archetype tends to shift questions of financing and technological skill off into the shadows. A perk of genius, readers may simply assume, is the ability to obtain whatever resources are necessary for any given plan.

In Cory Doctorow’s novella ‘Chicken Little’ (2010), the antagonist, Buhle, wants to engineer a bioweapon which will rewire human neurology to eliminate cognitive bias, making humans into accurate assessors of risk. Buhle’s motives are ambiguous, but his disregard for medical ethics, and his eagerness to profit commercially from the transition, are sufficient to establish him as a bioterror villain.

Buhle is a ‘vat’ person, a quadrillionaire who enjoys artificial longevity. What is interesting for our purposes here is how clearly the novella shows the narrative continuities between corporation, state, and ‘evil genius’ as originators of bioterror attacks. Buhle is quite literally a blend of all three. ‘Somewhere in that tangle of hoses and wires was something that was technically a person, and also technically a corporation, and, in many cases, technically a sovereign state’ (Doctorow 2010).

Rogue scientistsSecretive government-sponsored bioweapons programs remain a common theme in contemporary pandemic narratives. This propagates an out-dated belief that only governments or powerful corporations, or individuals endowed with genius, have adequate resources to pose such a threat.

However, the ‘rogue scientist’ presents an intriguing intermediary figure. As a step towards fictionalising a self-financed individual threat, we find narratives where rogue scientists misuse access to resource-rich laboratories. In David Moody’s 2012 short story, “Joe & Me”, Gill, a scientist working on a project funded by the military, becomes critical of how the government decides to use her research, which is aimed at preventing bioterrorism by saturating the global atmosphere with anti-viral agents. The government plans to instate a total biological surveillance system that would detect and annihilate any emerging biological threat. Gill realises that such system itself is a threat. She believes correctly that it has a catastrophic vulnerability, and tries to subvert the system’s launch. But her rogue experiments to neutralise the government’s plans spark a pandemic, leading to billions of deaths. Gill is presented as an ordinary scientist, one amongst many. In this story, the real enemy of humanity is the military which in its quest for omnipresent ‘defence system’ creates the mechanism for the world’s downfall. As in Orwell’s 1984, total surveillance justified by the need to fight terrorism is presented as a recipe for apocalyptic end to the world as we know it.

An interesting point of comparison is Vernor Vinge’s Rainbows End (2006), where the rogue character, who abuses access to official resources, is a high-ranking intelligence operative. It is, ironically, the fear of a lone wolf bioterror apocalypse that prompts Alfred Vaz to begin developing his own distinctive bioweapon, designed to rewire humans into a more easily controllable state. ‘There were a dozen research trends that could ultimately put world-killer weapons into the hands of anyone having a bad hair day’ (Vinge 2006, 18). While there may be some idealistic aspect to Vaz’s motives, as there are to Gill’s, they are sharply opposed in their attitudes toward totalising surveillance and supervision.

Margaret Atwood’s 2003 novel Oryx and Crake is a fruitfully ambiguous example of a “messianic” omnicide perpetrated by a rogue scientist. The scientist, Crake, develops a deadly bioweapon in the guise of a sex wonder drug, BlyssPluss. The human species is almost entirely destroyed by Crake’s engineered pandemic, in order to make way for his genetically modified human-like successor species: the peaceful, gentle, herbivorous Craker. Although Crake acts alone, Atwood does not neglect systemic factors in her depiction of apocalypse. Crake’s psychology appears to be shaped, albeit ambiguously, by his use of the internet,[2] and by the dehumanisation and commodification of women and girls. Crake’s actions also occur against a backdrop of deepening ecological crisis, economic inequality, and prolific, commercially-driven implementations of gene-editing technology. An eschatological ambience permeates Oryx and Crake, which deepens in the second novel of Atwood’s trilogy, The Year of the Flood (2009). The Year of the Flood covers a similar time-frame from different perspectives, notably that of the God’s Gardeners, a cult or sect whose teaching draws on Christianity, deep ecology, and survivalism. Readers may be left with the impression that had Crake’s lone wolf bioterrorism not triggered an apocalypse, some other apocalypse would have come along soon enough.

Chuck Hogan’s The Blood Artists (1998) represents a hybrid narrative between a natural pandemic and an act of bioterror. In this novel, an environmentalist becomes infected with an emergent virus while on a trip to Africa. He and the virus evolve into a single entity, reaching a common goal to eradicate human ‘infection’ from the planet for the benefit of all other species. What is particularly interesting about the novel, in relation to lone wolf bioterrorism, is that the apocalyptic threat is represented by a mediocrity. The bioterrorist in The Blood Artists, nicknamed Zero for being the first to survive the infection, is indeed a zero, a nobody. Zero is an ordinary scientist, and yet he very nearly succeeds in killing every last human being. By being unremarkable, he epitomises a very modern kind of catastrophic threat.

Prophets of pandemicSome authors go further, portraying characters who do roughly resemble the figure of the lone wolf bioterrorist, working out of a makeshift lab, that the academic biosecurity literature outlines. The rest of this article will consider, in slightly more detail, four such characters. The ‘ordinariness’ of these characters is, however, not straightforward. In Greg Bear’s Quantico (2005) and Stephen King’s “The End of This Whole Mess” (1986), there is a mismatch between the character’s subjective sense of their own historical importance, and the ordinary status assigned to them by society. This mismatch is part of the process which draws the character to bioterror. In HW ‘Buzz’ Bernard’s Plague (2012) and Tim Downs’s Plague Maker (2006), ordinary lives conceal repressed trauma, which finds expression in the hyperviolence of bioterror.

Greg Bear’s Quantico presents an alternative narrative for the 2001 Anthrax attack: the terrorist responsible was not Bruce Ivins, but a fictional character, Tommy. Tommy, who has managed to evade the FBI until it is too late, represents the lowest denominator threat: a high‑school drop-out, experimenting with microbes in the basement of his family home. Tommy perfectly fits Ackerman and Pinson’s (2014) profile for such a terrorist – a ‘solipsistic misanthrope’, someone who would never be able to ‘function socially as a part of an operational terrorist group’, but who nevertheless harbours ‘grandiose aims of deeply affecting the system’.

The change that Tommy wants to engineer is a recurring theme of science fiction: a world without violence. One pervasive suggestion is that defanging humanity out of its violent impulses is tantamount to a death sentence for civilisation. A closely related idea appears in Doctorow’s ‘Chicken Little’, in which bioengineered “perfect” risk assessment leads to a plummet in the birth rate. Both H.G. Wells in The Time Machine (1895) and Kurt Vonnegut in Galapagos (1985) associate the loss of aggression in society, in the course of future human evolution, with a concurrent loss of language, arts and sciences.

It does not matter for this ‘essentialist’ idea whether humanity loses the potential for violence gradually over thousands of years, as in The Time Machine and Galapagos, or overnight, as in Stephen King’s 1986 short story “The End of the Whole Mess”. The underlying assumption of these narratives seems to be that civilisation needs its dark side to persist. King’s short story could have been an inspiration for Greg Bear’s Quantico, written twenty years later, so similar are the apocalypse scenarios. In “The End of the Whole Mess”, Bobby, an amateur scientist and a social outsider, dismayed at a world engulfed by violence and wondering, “Why are people so goddam mean?”, discovers a protein which turns the violent impulse off. Unfortunately, it also destroys memories, then infantilises, then kills. Bobby tests his product only on bees and so does not realise that these side-effects exist. He engineers a self-replicating and contagious version of the protein and convinces his older brother to help him release it into the global atmosphere, whereupon every single person on earth dies. In Bear’s Quantico, Tommy also engineers a contagious protein, derived from Mad Cow Disease, aiming to disrupt memories of conflict and with that to halt a cycle of violence. Tommy, like Bobby, is willing to risk total destruction of humanity in the process. The FBI tries but fails to prevent its global release. As in “The End of the Whole Mess”, everyone in Greg Bear’s fictional world would lose their memories, then die.

There are many similarities between King’s Bobby and Bear’s Tommy. Both identify as messiahs, someone tasked with saving the world. Bobby even imagines himself marked with stigmata:

‘The world,’ Bobby said, and then stopped. His throat worked. I saw he was struggling with tears. ‘The world needs heroic measures, man. I don’t know about long‑term effects, and there’s no time to study them, because there’s no long-term prospect. Maybe we can cure the whole mess. Or maybe – ‘

He shrugged, tried to smile, and looked at me with shinning eyes from which two single tears slowly tracked.

‘Or maybe we’re giving heroin to a patient with terminal cancer. Either way, it’ll stop what’s happening now. It’ll end the world’s pain.’ He spread out his hands, palms up, so I could see the stings on them. ‘Help me, Bow-Wow. Please help me.’

This perception of the world as hopeless, as ‘a patient with terminal cancer’ works to justify Tommy’s and Bobby’s actions from their point of view. The world in the near-future, as depicted by Greg Bear and Stephen King, has become more violent, closer to a point of rapture. The setting is millenarian.

This conceptualisation of a world seemingly approaching an end has been singled out by both literary scholars and risk experts as conducive to radical actions. Risk experts Ackerman and Potter (2008) summarise psychologists’ argument as:

It has been asserted that the ideologies most conducive to the pursuit of catastrophic violence are those which simultaneously reflect an apocalyptic millenarian character, in which an irremediably corrupt world must be purged to make way for a utopian future, and emphasize the capacity for purification from sins through sacrificial acts of violence.

‘Sacrificial acts of violence’ are precisely how Bobby and Tommy respond to the world they perceive as facing imminent existential risk. Biotechnology has given them means to do something about it. In this respect, they are very plausible characters. Psychologists have suggested that when thinking about existential risks, the human brain switches modes and as a result, people who are normally empathetic are able to contemplate extinction of the human species with utter detachment. According to Eliezer Yudkowsky – whose primary research is in AI and who has associated research interests in human rationality – ‘People who would never dream of hurting a child hear of existential risk, and say, “Well, maybe the human species doesn’t really deserve to survive”’ (Yudkowsky 2008, 106). Yudkowsky formulates this problem as a cognitive bias, understood computationally and neurobiologically:

The human brain cannot release enough neurotransmitters to feel emotion 1000 times as strong as the grief of one funeral. A prospective risk going from 10,000,000 deaths to 100,000,000 deaths does not multiply by ten the strength of our determination to stop it. It adds one more zero on paper for our eyes to glaze over, an effect so small that one must usually jump several orders of magnitude to detect the difference experimentally. (Yudkowsky 2008, 106)

This may be categorized as a ‘scope effect’ bias. What this means is that the inability to scale empathy is not some rare pathology, peculiar to a dangerous fraction of humans. Rather, it is an ordinary feature everyday human cognition. So in this respect, Bobby and Tommy are unremarkable.[3] If we seek a factor which distinguishes Bobby and Tommy, that factor is not their casual feeling toward existential risk.

What is it then? In this regard, perhaps narcissistic personality disorder is suggestive. Of course, no fictional character can be diagnosed, any more than they can be treated. Insofar as a character is a textual representation of a human, trying to diagnose its pathologies is like trying to go for a walk in a photograph of a forest. Nevertheless, psychiatric discourse can provide one useful lens through which to analyze the text’s construction of personality, perspective, motive, and action. One manifestation of narcissistic personality disorder, a spectrum disorder, which Jean M. Twenge and W. Keith Campbell (2009) suggest is on the rise, is a gross overestimation of one’s importance in the world’s culture or history. In the extreme case, this might mean identifying a personal destiny with the fate of an entire world. Such individuals may feel both a responsibility for the evil they encounter and a sense of moral duty to intervene. Bobby imagines himself as the surgeon tasked to excise the world’s cancer in an attempt to save its life. Tommy imagines that the world is sick because of him:

Tommy had sought to hide away from a world he knew was trying to find him, a world going to war (he believed he was partly to blame for that), a world that made unexpected and unwanted phone calls and sent him suspicious junk email with impossible promises and lures, a world he knew wanted all of his money and cared nothing for him – an inhospitable world he ‘thought’ was going completely mad.

Terrorism is an external trigger for both Tommy’s and Bobby’s actions. In Quantico, which is written in closer reference to historical events, the September 11th terror attacks in the USA are the traumatic trigger which sets Tommy on his path:

Then Sam punched in 09-enter-11-enter -01, the date Tommy believed had signalled the world’s descent into noisy madness.

The day that Tommy had decided anything he could do to strike out, to strike back, would be fully justified.

The September 11th attack is also the traumatic event which leads Sam, a former FBI agent, to adopt Tommy as a younger brother and assist him in releasing the ‘cure’. The infantile style of conversation between Tommy and Sam is reminiscent of the simplified childlike logic with which Bobby and his brother Bow-Wow discuss their plans. Possibly, the authors want to highlight the new turn: ‘we used to be worried about children playing with matches, now we need to be worried about children playing with biotech’. Tommy is to be feared only because new developments in biotechnology enable him to implement his immature fantasies:

Revenger’s pandemics‘The whole world’s fighting and we’ll help them stop fighting. It’ll be a lot quieter. That’s worth something, isn’t it? I’ve learned a lot from you, Sam.’ …

‘Right, Tommy,’ Sam said. ‘You and me, we’re going to cure the planet.’

‘I love you, Sam,’ Tommy said. ‘You saved me. I hope I can return the favor.’

‘You’re the man, Tommy. You’re the one we’re all going to owe favors to someday.’

Tommy and Bobby are infantilised terrorists, as their names suggest. We fear what they may do, but we don’t fear them personally. The typology of fictional bioterrorists contains another, more traditional group. These are men of hatred, in pursuit of vengeance, that opt for biotechnology because it is expedient.

They make an appearance in two American novels that feature lone wolf terrorists as engineers of germs capable of sparking an apocalyptic global pandemic: Alnour Barashi from Iraq, in HW ‘Buzz’ Bernard’s Plague (2012), and a Japanese national called Sato Matsushita in Tim Downs’s Plague Maker (2006). Both are motivated by an unconstrained hatred of America, deriving from traumas suffered from American interventions in the Middle East and Hiroshima, respectively. Both are scientists who learned the tricks of the trade in Russia, participating in Biopreparat, the historically factual Soviet bioweapons program. Sato, who unusually for a (fictional or non-fictional) terrorist, is in his eighties, started his career in bioweapons during WWII as part of Japanese Unit 731 which allegedly tested biological weapons on Chinese subjects during the war.

The action of both thrillers is set in the beginning of the 21st century. Sato engineers a super-infectious and antibiotics-resistant version of the bubonic plague, while Alnour Barashi assembles ‘a recombinant Ebola virus as easily transmittable as the common cold’ (fly leaf). Both work independently in makeshift labs, but have associates to help spread the pathogens as back-up plans in case they are apprehended. The plots in both novels are broadly similar: we follow heroic efforts of various individuals to prevent the impending attack, the terrorists are killed, yet it is left open as to whether the pandemic is inevitable. Pathogens once created by bioterrorists are easy to hide and hard to find – a key source of risk highlighted by novelists and experts.

Unlike Tommy and Bobby who crave recognition, both Alnour and Sato act out of personal grievances and are comfortable with remaining anonymous. Their audience is limited to private beliefs, with no outside validation. Alnour is motivated by religious piety trying to please his God, while Sato believes his revenge will release aragami from a curse – a restless spirit of Sato’s sister who was killed at Hiroshima. Both Alnour and Sato are racially stereotyped in the respective texts. The all-American protagonist of Plague is a successful, fearless and moral CEO, who – we learn in the afterword – is modelled on the author’s good friend. This is how Alnour is shown through the protagonist’s eyes:

Wolfish. Dark. Cold. Yet burning with the intensity of lasers. They seemed to radiate something primitive, carefully cultured, nurtured from generation to generation – if not genetically, then certainly socially: unrelenting, unapologetic hatred.

Although both authors delve into the psychology of terrorists by describing past traumatic experiences, Sato’s experience of discovering the burned body of his sister amongst the ruins of Hiroshima is arguably the most affecting part of the novel. Sato’s trauma is rendered in vivid emotional detail. Broadly speaking, both storytellers seem uninterested in fine distinctions grounded in actual psychiatric research, apparently opportunistically conflating features of PTSD, antiscocial personality disorder, and the complex and contested relationships between long-term childhood abuse and adult criminality, whilst being guided largely by the parameters of a revenge narrative. Their description of terrorist motivation is nevertheless consistent with some opinion on how terrorists of such kinds can emerge. Bostrom and Cirkovic (2008, 410) tentatively suggest: ‘It is believed that individuals from heavily brutalized and traumatized communities (such as those who fall victims of genocide) might be capable of unrestrained levels of violence.’ However, the research on the connection between trauma and terrorism is still highly uncertain. Bhui et al. (2014) carried out the first UK cross-sectional study involving 607 participants from areas with significant Muslim populations. The aims of the study were to highlight factors associated with vulnerability to radicalisation; no link was found between life trauma and risk of radicalisation.

One broad lesson we may draw from both novels is that research into lone wolf terrorists as not only perpetrators of violence, but also victims and witnesses of violence, must take in considerations of retribution and justice. In this connection, there is a narrative that unites these fictional accounts and connects to known historical precedents. Its basic structure is an erasure of a traumatic past. Speaking of ideologies supporting terrorism, Roy (2017) writes in the Guardian on April 13: ‘Memory is annihilated. “Wiping the slate clean,” is a goal common to Mao Zedong’s Red Guards, the Khmer Rouge and Isis fighters.’ Ideology in the context of bioterror may be little more than ideation about a clean slate. Grand narratives underpin the worldviews of the terrorist organisations, writes Roy (2017): ‘‘Certainly Isis, like al-Qaida, has fashioned a grandiose imaginary system in which it pictures itself as conquering and defeating the west. It is a huge fantasy, like all millenarian ideologies.’

What can we learn from these fictional accounts?There are many reasons why lone wolf actors may seek to develop bioweapons. Being in possession of a deadly weapon is a position of great power that can be exploited for profit, to act as a deterrant, or in order to achieve other objectives. Examples of blackmail scenarios include the TV series 24, in which an individual acquires a bioweapon and successfully uses it to blackmail the US president (24 Season 3, 2005), and the 2014 novel Resistant by Michael Palmer, in which a white supremacist terrorist group develops a flesh-eating, highly contagious bacteria, to blackmail the US government into adopting an anti-welfare agenda. Bioterrorists may initially hope to deploy bioweapons in a narrow, targeted fashion, as a substitute for conventional weapons. Or bioterrorists might deliberately aim to eliminate or drastically reduce the human population, inspired by the likes of The Voluntary Human Extinction Movement (www.vhemt.org), or by a hatred for humanity. Bioterrorists may be operating in a distinctively configured informational environment. They may perceive themselves to be acting in self-defence, or believe that by unleashing enormous violence, they may prevent still greater violence, as seems to be the case in works by Atwood, Bear, and King.

The action of developing and deploying bioweapons may of course also gather its own momentum, and even exhibit a certain independence from identifiable motives. For instance, the process may be sustained piecemeal by different motives at different moments. Mere curiosity, or a blinkered ‘design stance’, focused on technical problem-solving and neglecting, may also play a role. Even at any single moment, such action may depend on mixed, hybrid motivations. For instance, in the 2000 novel Bio-Strike by Jerome Preisler, Harlan DeVane plans to auction the superbug bioweapon he has developed, but also to use it in a personal vendetta. However, the extent to which motivational fluidity is reflected in fiction, where authors may be incentivised to create stylised, readily comprehensible villains in order to satisfy readers, remains an important question, and not one which this article has addressed in any depth.

The manifold possibilities of how lone wolf terrorists might arise might be presumed to generate a great variety of speculative characters. Yet characters who exploit the lowering thresholds of bioterror are less easy to find, in film or in literature, than one might expect. One recent study, focusing on scientist characters in high gross box-office movies, did not find the kind of “amateur” science which enables lone wolf bioterrorism:

The recent development of SB [Synthetic Biology] has triggered the emergence of a growing community of amateur biologists wishing to apply SB technologies, assemble DNA or rebuild whole viruses in their mobile labs, garage or kitchen (Wohlsen 2011, Schmidt et al. 2009b). These often called bio-hackers or bio-punks are mainly “college student(s) eager to demonstrate their technological prowess” (Kelle 2009, p.104). In the analysed movies, such an “amateur” scientist with his or her “homemade” synthetic organism cannot be found. The image of the SB scientist as “Do-it-yourself biologist” seems to be completely absent from the high gross box-office movies. (Meyer 2013)

Our limited survey of recent fiction has produced some examples of lone wolf bioterrorists who roughly approximate “amateur” scientists. These works serve to popularise a specific kind of existential threat to humanity, enabling us to picture the fate of the world, not in the hands of powerful governments or corporations, not even in the hands of men of genius, but in the awkward clutches of minor characters. In particular, King’s Bobby, Bear’s Tommy, Downs’s Sato and Bernard’s Alnour are easily substitutable. It is precisely this which makes these narratives good at illustrating the nature of the lone wolf terrorism threat.

One problematic aspect of these narratives is that they prepare the ground for the acceptance of an erosion of personal freedoms. Surveillance and expansion of the powers of counter-terrorism agencies is portrayed as the only feasible form of managing these risks. In the real world, mass surveillance and other ‘big data’ approaches are being tested, and there have been attempts to use machine learning for counter-terrorism strategies, as Confessore and Hakim (2017) report in the New York Times on March 6. Fictional bioterror narratives portray such intervention by the state as necessary for humanity’s survival. Surveillance technology is shown to be indispensable to the protagonists who kill Sato and Alnour, and who capture Tommy. They include: a CEO of a company, MOSSAD and FBI agents, a pastor, a Chinese convert to Christianity, a political scientist whose field is psychology of terrorism, and various epidemiologists and disease control experts. This set represents the pillars of American society in dominant discourse: Christianity, capitalism, security apparatus, and expert elites. The novelistic emphasis on surveillance technologies chimes with expert opinion that purports that although surveillance is politically problematic, it is needed to manage risks of biotechnology:

[…] it is unrealistic to expect that when the genie is out of the bottle, we can ever be fully secure against bioerror and bioterror: risks would still remain that could not be eliminated except by measures that are themselves unpalatable, such as intrusive universal surveillance. (Rees 2008, 88)

These four fictional lone wolf narratives all pull in the same direction as security studies discourse on policies needed to manage bioterrorism risks. The lack of divergence between novelistic and scientific imagination is disconcerting because it signals a truncated speculative space, potentially introducing biases to the public imaginary regarding ways in which bioterror risks posed by isolated, low-profile individuals should be managed. However, the sample of fictional scenarios is too small to draw general conclusions about parallels or discordances between novels versus security studies.

Eliezer Yudkowsky sees in fictional apocalyptic scenarios a danger to an ‘unbiased’ rational response. In his opinion, literary representations of existential risks are to be resisted:

We should avoid not only being duped by fiction – failing to expend the mental effort necessary to ‘unbelieve’ it – but also being contaminated by fiction, letting it anchor our judgment. … Not uncommonly in a discussion of existential risk, the categories, choices, consequences, and strategies derive from movies, books and television shows. There are subtler defeats, but this is outright surrender. (Yudkowsky 2008, 104)

Working in a critical and multidisciplinary way with this wider cultural context may be a third alternative to outright surrender or subtle defeat. We should certainly be cautious of thinking that we have escaped the influence of representations of bioterror merely by emphatically declaring their fictionality. Because there is so little historical evidence to ground a rational assessment of risks such as those posed by engineered pathogens, any basis for constructing scenarios will be speculative and subjective. There is no scientific alternative to imagination. The skills required to understand how cultural, political and ideological factors influence the construction of risk scenarios differ from the skills in which most scientists are trained. In his essay “Versions of Apocalypse” Christopher Norris (1995, 242) makes a pragmatic suggestion which is to recognise, within the field of existential risk, the authority of those who are ‘expert mainly in the reading of texts’.

One danger is that in consulting experts on literary and cultural objects, biosecurity researchers may simply find their own expertise reflected back at them. In contemporary publishing and film industries there is a growing tendency to consult scientific opinion when describing existential risks; film producers believe that plausibility translates into higher earnings at the box-office and scientists welcome exposure that might increase public willingness to finance research needed to confront these risks (Kirby 2010). Film directors employ scientific consultants, and writers attest to personal contact and collaborations with scientists. There are even scientists who themselves turn to fictionalising their research, such as Joann Mead, a biotechnology researcher and an author of two bio-crime novels. Her Amazon.com profile says: ‘Joann Mead is a writer, teacher and researcher. Her first bio-crime novel, “Underlying Crimes”, was inspired by her published research on disasters and emerging threats. She brings her unique perspective from teaching science in four countries (United States, United Kingdom, Russia and Zimbabwe), working in biotechnology and in medical research’.

Although it is difficult to draw general conclusions from the small sample of works considered in this article, the authors seem to strategically position their work in relation to societal discussion of pandemic risk. In order to increase their relevance to this public conversation, they employ technical knowledge in formulating aspects of the plot and openly cite their research in paratexts. In the novels examined, even the characters of lone wolves seem to be based on profiles emerging from security studies (Spaaij 2012). In Quantico, Greg Bear insists in the ‘After Note’ that the threat he portrayed is realistic; he states that he has ‘tried to persuade of the dangers without providing salient details. The dangers are real, and immediate’. Chuck Hogan in The Blood Artists and H.W. Bernard in Plague both mention in their ‘Author’s Note’ scientific sources supporting their narratives.

This entanglement of science/business/politics and fiction is anticipated by Jacques Derrida in his 1984 essay “No Apocalypse, Not Now”, according to Norris (1995). Apocalypse exists only as an imaginary phenomena, ‘a fable’, because if we are reading about it, it has not happened yet. But ‘a fable’ itself poses a risk by encouraging societies to take defensive actions to allay a perceived threat: ‘It is the war (in other words the fable) that triggers this fabulous war effort, this senseless capitalization of sophisticated weaponry’. Here Derrida is talking about nuclear apocalypse, but the logic translates to governmental ‘gain of function’ research where pathogens are made more virulent in order to be prepared for engineered or natural pandemics. As with the nuclear arms race, germ research is motivated by imagining that somewhere there is an enemy. The dependency between imagining risks and implementing policies to manage them requires closer attention to be paid to fiction. As Derrida warns, we have arrived at a point in history where ‘one can no longer oppose belief and science, doxa and episteme’ because technology posing globally catastrophic risks ‘coexists, cooperates in an essential way with sophistry,’ with the literary. In a world of AI, 3D printing, editing tools for genetics, or technologies for surveillance of thoughts and emotions, the fictional and non-fictional cannot be disentangled, not at the pace science and technology are evolving. Steering such a world away from a catastrophe requires insights from both scientific and literary domains, while also requiring that such domains maintain a degree of independence. A closer collaboration between scientists, writers and literary scholars could enable governments to anticipate and prepare for a wider range of scenarios, but there are also risks that such ideas will not be a reflection of possibilities in the minds of lone wolf terrorists, but rather the inception of new ideations and plans. Ideas have always had a life of their own, new information technologies only accelerate and exaggerate their mutation and spread to an extent that assessing risks might influence the probability of events assessed.

ReferencesAckerman, G.A. and Pinson, L.E. 2014. “An Army of One: Assessing CBRN Pursuit and Use by Lone Wolves and Autonomous Cells”. Terrorism and Political Violence. 26:226-245. DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2014.849945.

Atwood, Margaret. 2003. Oryx and Crake. London: Bloomsbury.

Bhui, Kamaldeep, Warfa, Nasir, and Jones, Edgar. 2014. “Is Violent Radicalisation Associated with Poverty, Migration, Poor Self-Reported Health and Common Mental Disorders?” PlosOne. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090718.

Bleek, Philipp C. 2011. “Revisiting Aum Shinrikyo: New Insights into the Most Extensive Non-State Biological Weapons Program to Date.” NTI. http://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/revisiting-aum-shinrikyo-new-insights-most-extensive-non-state-biological-weapons-program-date-1/

Bostrom, Nick and Cirkovic, M. ed. 2008. Global Catastrophic Risks. New York: Oxford University Press.

Confessore, Nicholas and Hakim, Dany. 2017. “Data Firm Says ‘Secret Sauce’ Aided Trump; Many Scoff.” The New York Times. March 6. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/06/us/politics/cambridge-analytica.html?&_r=0

Corner, Emily and Gill, Paul. 2015. “A False Dichotomy? Mental Illness and Lone-Actor terrorism.” Law and Human Behavior. 29 (1): 23-34. DOI: 10.1037/lhb0000102.

D’Arcangelis, Gwen. 2015. “Defending White Scientific Masculinity.” International Feminist Journal of Politics. 18 (1): 119-138. DOI: 10.1080/14616742.2015.1051330.

Doctorow, Cory. 2010. “Chicken Little.” In David G. Hartwell and Patrick Nielsen Hayden (eds.), Twenty-First Century Science Fiction. New York: Tor.

Doherty, Peter C. 2013. Pandemics: what everyone needs to know. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gable, G. and Jackson, P. (2011) Lone Wolves: Myth or Reality? Ilford: Searchlight Magazine.

Kearns, Erin M. and Betus, Allison and Lemieux, Anthony. 2017. ‘Why Do Some Terrorist Attacks Receive More Media Attention Than Others?’ (March 5, 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2928138

Kirby, David A. 2010. Lab Coats in Hollywood: Science, Scientists, and Cinema. London: MIT Press.

MacKenzie, Donald. 2006. An Engine, Not a Camera. London: MIT Press.

Meyer A., Cserer A. and Schmidt M. 2013. “Frankenstein 2.0.: Identifying and characterising synthetic biology engineers in science fiction films.” Life Sciences, Society and Policy. 9:9. DOI: 10.1186/2195-7819-9-9.

Mumford, John D., Leach, Adrian W., Holt, Johnson, Suffert, Frédéric, Sache, Ivan, Benedicte Moignot, and R. Alexander Hamilton. 2017. “Integrating Crop Bioterrorism Hazards into Pest Risk Assessment Tools.” In Practical Tools for Plant and Food Biosecurity, edited by Gullino, ML., Stack, P., Fletcher, J., and Mumford, JD. Cham: Springer.

Norris, Christopher. 1995. “Versions of apocalypse.” In Apocalypse Theory and the Ends of the World, edited by Bull, Malcolm. Oxford: Blackwell.

Nouri, Ali and Chyba, Christopher F. 2008. “Biotechnology and biosecurity.” In Global Catastrophic Risks, edited by Bostrom, Nick and Cirkovic, M. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nusaybah, Abu. 2014. Interview on BBC Newsnight, given on 24 May 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BqL5d1IWu9s.

Preisler, Jerome. 2000. Tom Clancy’s Power Plays: Bio-Strike. Penguin Random House.

Rees, Martin. 2003. Our Final Century. London: William Heinemann.

Robb, John. 2008. Brave New War: The Next Stage of Terrorism and the End of Globalization. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Rowland, Christopher. 1995. “‘Upon Whom the Ends of the Ages have Come’: Apocalyptic and the Interpretation of the New Testament.” In Apocalypse Theory and the Ends of the World, edited by Bull, Malcolm. Oxford: Blackwell.

Roy, Olivier. 2017. “Who are the new jihadists?” The Guardian. April 13. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/apr/13/who-are-the-new-jihadis

Selk, Avi. 2017. “Bill Gates: Bioterrorism could kill more than nuclear war — but no one is ready to deal with it.” The Washington Post. February 18. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/02/18/bill-gates-bioterrorism-could-kill-more-than-nuclear-war-but-no-one-is-ready-to-deal-with-it/

Shane, Scott. 2011. “Panel on Anthrax Inquiry Finds Case Against Ivins Persuasive.” The New York Times. March 23. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/24/us/24anthrax.html

Spaaij, Ramon. 2012. Understanding Lone Wolf Terrorism: Global Patterns, Motivations and Prevention. Netherlands: Springer.

Stewart, George R. 1969. Earth Abides. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Suffert, Frédéric. 2017. “Characterization of the Threat Resulting from Plant Pathogen Use as Anti-crop Bioweapons: An EU Perspective on Agroterrorism.” In Practical Tools for Plant and Food Biosecurity, edited by Gullino, ML., Stack, P., Fletcher, J., and Mumford, JD. Cham: Springer.

Thompson, Mark. 2013. “The Danger of the Lone-Wolf Terrorist.” Time. February 27. http://nation.time.com/2013/02/27/the-danger-of-the-lone-wolf-terrrorist/

Twenge, Jean M and W. Keith Campell. 2010. The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement. NY: Atria Paperback.

Vinge, Vernor. 2006. Rainbow’s End. NY: Tor.

Wald, Priscilla. 2012. “Bio-Horror”. In Contagion: Health, Fear, Sovereignty, edited by Magnusson Bruce and Zalloua Zahi. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Yudkowsky, Eliezer. 2008. “Cognitive biases potentially affecting judgment of global.” In Global Catastrophic Risks, edited by Bostrom, Nick and Cirkovic, M. New York: Oxford University Press.

Footnotes[1] The label, which has wide currency, has at least two drawbacks. First, even where an actor has received no practical assistance from any organisation, we must take care not to sideline the potential explanatory force of social complexes that are too diffuse to be regarded as organisations. The term ‘lone wolf terrorist’ may somewhat exaggerate the isolation of an actor from the variety of institutions that inform, motivate, and structure action. This is of course a disadvantage which it shares with obvious alternatives such as ‘lone terrorist actor’. Second, the term is implicated in politically charged debate around how terror incidents – or incidents whose status as terror is contested – are narrated in the media. For instance, a report by the UK-based antifascist organisation Searchlight, ‘Lone Wolves: Myth or Reality?’ offers numerous profiles of terrorists whom it argues have been mischaracterised as lone wolves (Gable and Jackson 2011). Research into US media coverage of recent terror incidents finds that the perpetrator’s social identity has been the largest predictor of the level of coverage, ahead of factors such as target type, arrest of perpetrator, and number of fatalities (Kearns, Betus and Lemieux, 2017).

[2] Digital affect is also a crucial factor in turning Greg Bear’s Tommy (discussed shortly) towards terrorism, even though physically he is distant from violence. In Greg Bear’s Quantico and Stephen King’s “The End of All This Mess”, information technology is shown to not only enable technical knowledge to pass into the wrong hands, but also to cultivate a millenarian sense of the world’s corruption, even when – as in Tommy’s case – residing in one the safest places on earth, a secluded vineyard in California.

[3] We might also question Yudkowsky’s ‘funeral unit of grief’, and by extension, whether treating all forms of human rationality as ultimately reducible to calculative rationality is itself a rational thing to do. It does, after all, put us uncomfortably close to the position of Doctorow’s bioterror villain Buhle (q.v.). Would empathy really be improved if it were additive in the way implied? Would it still be empathy? It is of course clearly possible to feel strong sorrow and revulsion at the death of millions, and this feeling is not aggregated from millions of microcosms of itself; it is its own intelligible affective structure, with its own forms of cultural and social mediation. Approaches like Yudkowsky’s, grounded in or adjacent to behavioural economics, can be usefully challenged and complemented by ecocritical philosophy which also explores things that are too big and complex to think through properly (this includes Timothy Clark’s discussion of “scale framing” (Clark 2015, 77-112) and Timothy Morton’s “hyperobjects” (Morton 2010 and 2013)).

Share this: