You who set free love’s bright syllable

from behind history’s iron door

that those who choose to take heed

may stride toward the sky

from “Voice” by John Agard

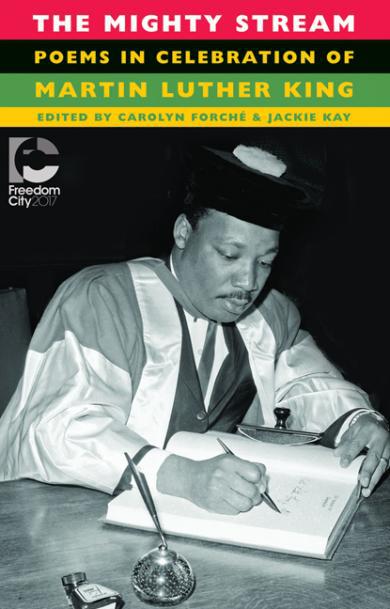

In the last post before Christmas, a package arrived for me from Newcastle. It was a book of poems, The Mighty Stream: Poems in Celebration of Martin Luther King edited by Carolyn Forché and Jackie Kay (Bloodaxe 2017) that came along with a thank-you for my work on the “Diverse Voices? Curating a National History of Children’s Books” symposium in November. Both the symposium and the poetry collection I received were part of Newcastle’s “Freedom City” project, which commemorated the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s visit to the city to receive an honorary doctorate from Newcastle University just months before he was assassinated.

The idea of commemorating such an event is a good one, especially with events and publications that speak not only about the past, but about the present and future. The Mighty Stream includes poems that discuss King’s life, but also the life and death of Trayvon Martin. Lauren Alleyne’s “Martin Luther King Jr Mourns Trayvon Martin” includes the lines, “For you, gone one, I dreamed/ justice—her scales tipped/ away from your extinction” (187). Our “Diverse Voices?” symposium looked at the past, through archival work, but also pointed out the work that needed to continue—in publishing, in archiving, in prize-giving. Both book and symposium also discussed the need for everyone—everyone—to use their own voice to call out injustice. John Agard’s poem “Voice,” quoted at the beginning of this blog (and on page 47 of The Mighty Stream), is the optimistic and hopeful counterpart to Ifeoma Onyefulu’s comment at the symposium, “It’s good to talk, but where’s the action?” Calling out injustice is one piece of the puzzle, but unless (as Gandhi put it), “your words become your actions, your actions become your habits” then words are not enough.

Brahmachari continues the Levenson family saga with a twelve-year-old girl finding her voice–and sharing it with the world.

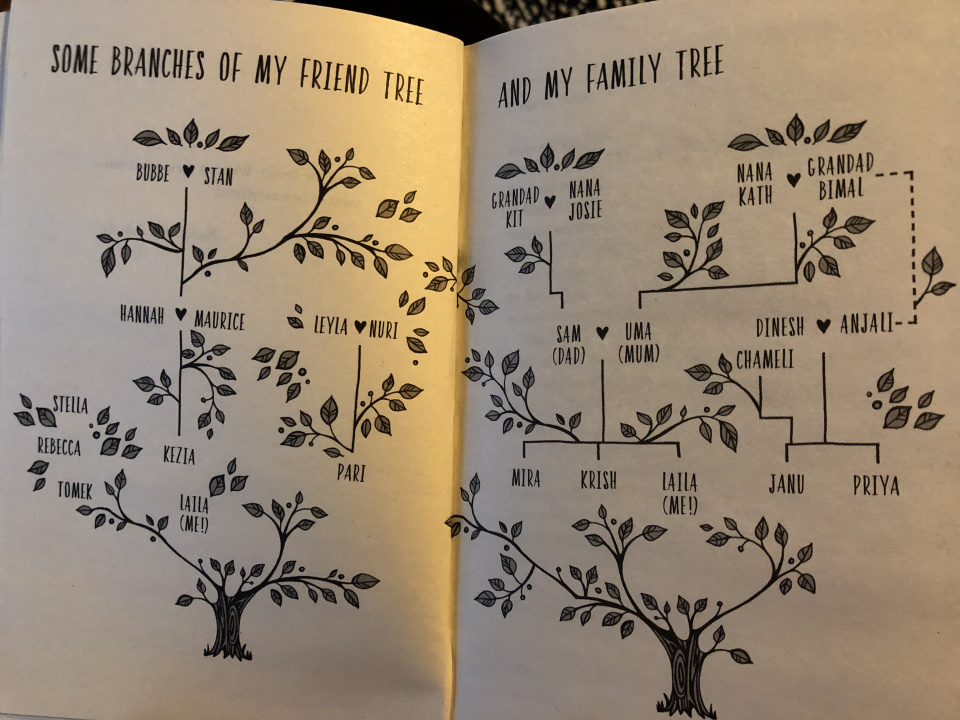

One of the authors at the symposium in November, Sita Brahmachari, recently published a book that puts Gandhi’s ideas into practice. Tender Earth (Macmillan 2017) forms the latest book of her fictional Levenson family’s history, but it is also a story of justice born out of (often painful) experience. Brahmachari’s earlier books, Artichoke Hearts (Macmillan 2011) and Jasmine Skies (Macmillan 2012) focused on the eldest Levenson girl, Mira, as she finds out who she is through art and travel. Both these journeys of discovery involve Mira’s family in important ways; art is a gift of Mira’s Nana Josie, and Mira travels to India to stay with her mother’s side of the family and learn about her heritage. Family also plays an important role in Tender Earth, about the youngest Levenson sister Laila, but Brahmachari’s novel expands the definition of family to include a wider group of people. Indeed, the book begins with two trees—a traditional family tree, and Laila’s “Friend Tree”. Her friend tree comes first, indicating its central role in the novel.

Laila’s friend and family trees give her a place on this tender earth that is both local and global.

Friends are perhaps central to Laila because her family is breaking up, not in a negative way but in the normal course of things. Her sister Mira is going to Glasgow to study art at university; her brother Krish has also departed, to the Lake District to live with Nana Kath. Laila feels uncertain about her place in the family, as indicated by her new choice of “bedroom”—a couch on the liminal space of a stair landing, “a seat . . . like it’s a waiting room” (253) as one person comments. At first, it seems old friendships are also breaking up. Laila’s best friend Kez won’t come over anymore because she is in a wheelchair and Laila’s house is difficult for her to access—but Kez has also arranged to be placed in a different tutor group than Laila, a move that Laila sees as a betrayal. But being thrown onto her own resources necessitates Laila’s growth. She makes a new friend, Pari, whose parents are Iraqi refugees, and meets her Nana Josie’s old friends Hope and Simon. Simon gives Laila her deceased Nana’s “Protest Book” which lists a lifetime of social justice marches and activities. These new friendships, a visit from Laila’s Indian cousin Janu, who is going around the world barefoot to raise money for his charity, and a sympathetic teacher’s gift of the biography of Malala Yousafzai, all work together to point out a direction for Laila. She sees that what she’s been “waiting for” in her liminal space was a purpose, an identity.

Laila brings her new and old selves together by organizing her first protest. When Laila’s friend Kez’s grandmother goes to visit the grave of her Kindertransport husband, it has been spray-painted with a swastika along with several other graves in the Jewish cemetery. Laila witnesses the way the desecration of the graves devastates Kez’s family, and decides to mount a candlelight protest. Her thought process is recorded by Brahmachari:

“Everything kaleidoscopes through my mind. Those men’s faces on the tube, mocking Janu with their chanting, the hateful words in Pari’s lift, what her parents had to go through, Bubbe and Stan arriving as children, Grandad Kit marching on Cable Street against the fascism growing in the city, Bubbe’s tears at the refugee children on the news, at Stan’s grave . . . what if . . . what if no one can tell when they’re actually living in a time that’s losing its heart? What if that’s why evil things happen? No one says and does anything until it’s too late” (380).

Laila’s protest brings together all the people she has met because they all can say and do something to help make things better. One of the things Brahmachari does so well as a writer is to draw characters as whole people; Pari’s mother may be a refugee living in poverty whose English is imperfect, but she too has a voice and can take action. She not only comes to Laila’s protest, she knits Laila a warm hat. Everyone, Brahmachari argues, has something tangible that they can give to a community—no matter how liminal they may seem.

So in the spirit of the coming new year, and in the hope posited by events such as the Women’s March last January (an event mentioned in Tender Earth) and the “Diverse Voices?” symposium, I am going to think about ways to use my voice in 2018—and put my words into actions until they become habits. Maybe you can do the same, and love’s bright syllable will help us all stride skyward.

Advertisements Share this: