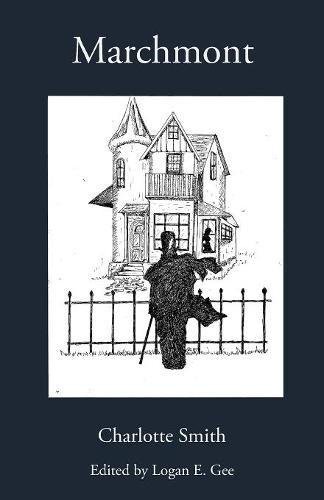

A new edition printed by Whitlock Publishing

Marchmont is utterly unlike any of the other early gothic novels I have read thus far. Charlotte Smith adopts many of the typical characteristics of the gothic (such as a female protagonist, eerie settings, ruinous castles, ghosts, and unscrupulous villains) but executes each of these elements with a realism unrivalled by her contemporaries and uses them to explore and the social and political problems of 18th century England.

The novel opens on the near idyllic life of Althea Dacres, who lives with her unmarried aunt Mrs. Trevyllian. Together they enjoy a solitary life away from the shallow distractions of high society but when her aunt becomes ill and eventually dies, Althea is sent to live with her father and step-mother and soon encounters many new dangers–the first of which is marriage. When Althea refuses to marry a man she can neither love nor respect, her parents punish her by sending her to live in the old, isolated, and partially ruinous Eastwoodleigh castle. As cliché as this might sound, Smith fleshes out her story with my realistic details and creates an effectively eerie setting.

What makes Eastwoodleigh castle so eerie is not the possibility of it being haunted but its desolate condition and the sequence of events that robbed it of all its comforts. Once the home of a proud and illustrious family, the castle stands as a sad testament to the usurious practices of debt collectors. Falling on hard times, the Marchmont family borrows a considerable amount of money in order to keep their ancestral home in the family but when they are unable to pay back this money they are forced to sell many of their personal belongings, stripping the castle of it finer furnishings and selling all the old-growth trees for wood. Their efforts ultimately come to naught. They are sued by their creditors and hounded by an unscrupulous lawyer called Vampyre, who exploits their ignorance of the law to the benefit of his client and to the ultimate ruin of the Marchmont family. Lord Marchmont takes his own life (a controversial detail Smith subtly alludes to), leaving his wife and three daughters living in poverty while his only son struggles desperately to earn money to support them.

To Althea, Eastwoodleigh castle initially presents itself as refuge, rather than as a punishment, and appeals to her romantic sensibility. She doesn’t mind a simply, solitary life away from society, as long as she has her aunts books and has some company. Even her step-mother tries to scare her into submission by mentioning rumors of the castle being haunted, Althea is hardly perturbed. Yet when she arrives she soon discovers that her new home is not exactly the romantic refuge she had envisioned. Her isolation and the dreary conditions of the castle begin to oppress her spirits and work its devious magic on her imagination. While Smith does employ the explained supernatural occasionally throughout her novel, they are often slight and quickly explained away. At first, these suggestively supernatural scenes seem disappointing but by rationalizing the supernatural Smith pulls the reader back down to earth and reminds them of the real dangers threatening Althea—namely poverty, ignominy, and Vampyre.

Vampyre is not the typical villain of gothic literature. He is a mere attorney, old and half-blind, but he knows how to exploit others to his and his client’s benefit and has few qualms about doing so. In her introduction, Smith mentions that Vampyre is based on an attorney she herself hired to represent her in the long, drawn-out legal battle over her father-in-law’s legacy. From other sources I have read, I understand that this attorney deliberately misinformed her and needlessly prolonged the case in order to change her more for his services. She also points out, in her introduction to Marchmont, that Vampyre is a softened portrait of the actual attorney because his “most hideous features are too offensive to be painted in all their enormity.” (Considering the nefarious deeds Vampyre commits in the novel, I shudder to think of the “offensive features” Smith only alludes to.) Although Vampyre’s many crimes never excel to the gruesome deeds of other gothic villains, Vampyre is fearful nonetheless, not only because he is powerful, but because he knows, as Smith reminds the reader throughout, that the legal system is designed to benefit the few and the affluent at the expense of the poor and vulnerable.

Althea fears Vampyre and his henchman, knowing well that her own situation is very precarious, but she is not afraid defy convention for the sake of what she believes right and true. When Althea discovers that Edmund Marchmont is indeed hiding in Eastwoodleigh castle, she considers the social consequences of her, a young unmarried woman, remaining within the same house as a young, unmarried man but ultimately determines to defy social norms despite the consequences in order to help a friend in need. Having been essentially abandoned by her only family, she reasons that she owes little to the rules of a society that has utterly resigned any responsibility to her well-being and therefore can no longer obligate her to follow its arbitrary rules when they conflict with her altruistic values. Smith imbues her protagonist with a strong, independent mind and, much like Ann Radcliffe, uses the gothic genre to explore how gender norms often disadvantage women socially.

Eighteenth century gothic novels are a mixed bag. Some are masterpieces of suspense and imagination, others are more shock than substance, and many more are poor imitations of more popular works but Marchmont stands out to me for the same reason Emmeline (also by Smith) did. Her characters feel so real and react to the world with a touching honesty. The problems they face reflect those that many people faced at the time when Smith wrote it, that she herself suffered through and never really overcame. It’s hard for me not to sympathize with her them and their plight or to recognize that the world is still haunted by the same ominous specters of vampiric greed that menaced many in the 18th century.

Smith’s works have long been neglected and have only recently received serious critical attention. In fact, when I was first introduced to her work, I was lead to believe that her later works were inferior to her early first novels but after reading Marchmont, her ninth novel, I simply cannot believe it. Marchmont is a well-written gothic romance that addresses the social problems of the 18th century with both great intelligence and wit. It won’t necessarily thrill you with suspenseful terror or shock you with gruesome horror but it will show you an oft forgotten political depth to the gothic that is still be relevant today.

* * *

Marchmont is currently available in an affordable paperback edition (pictured above) from Whitlock Publishing. Although the Whitlock edition does contain a number of typos, they do not interfere with reading, it is a welcome sight to see among the many cheaply produced, over-priced reproductions that proliferate like rabbits on Amazon.

Advertisements Share this: