ONE of the earliest crimes I ever became aware of took place just a few kilometres from my home. It wasn’t recent and it wasn’t widely discussed between neighbouring farmers. My mother whispered what she knew of the story one afternoon, in between social tennis matches at the Myall Creek courts adjacent to the old tin hall where we gathered for community events.

The 1838 Myall Creek Massacre has haunted and inspired me ever since, in much the same way it has done for generations of grazier families in the uplands between Delungra and Bingara in the Northern Tablelands of New South Wales.

Haunted, because there is justifiable guilt attached to the murder of innocent Aboriginal people. Haunted, too, because white men were hanged for the killings, for the first time in Australia’s history. Inspired, because the massacre memorial has become one of the most enduring actions of reconciliation this country has experienced.

In 2016, two new books, pitched as seminal to an understanding of this hateful crime against innocent Aboriginal people, were published. I read with interest, not only because I am indirectly writing about the massacre, but also because I was part of the great ignorance about this pivotal moment in modern Australia.

The more we read about it, the more we come to understand the inherent racism and inhumanity that fuelled it, the closer we get to shuffling off the fundamental penal colony principles this country still practices when it comes to race relations.

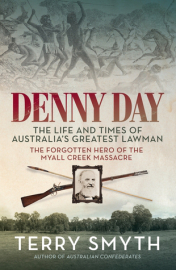

Terry Smyth’s Denny Day, the Life and Times of Australia’s Greatest Lawman (Penguin Random House) adds two critical elements to the analysis of the Myall Creek Massacre that I have not encountered before.

Terry Smyth’s Denny Day, the Life and Times of Australia’s Greatest Lawman (Penguin Random House) adds two critical elements to the analysis of the Myall Creek Massacre that I have not encountered before.

The first is the suggestion that part of the motivation for the killings was the habit of utilising Aboriginal trackers in the recapture of escaped convicts; that the massacre was, in part, justified by the convicts among the killers as payback for Aboriginal participation in Colonial justice. But Smyth doesn’t provide much direct evidence or make an argument for any of this, leaving him wide open to accusations of victim-blaming.

The second is Smyth’s courage in including the oral history about the exact nature of the crimes, as witnessed by an Aboriginal man who was not permitted under Colonial law to give evidence at either of the trials.

Most if not all of the writing on the Myall Creek Massacre stems from a desire to ‘own’ the story, or meet another storytelling agenda, and Smyth’s book adds to a growing list of titles that view the events from one strong angle.

However, by including the description of the crimes themselves – horrid, gutless acts of evil – Smyth has done a great service that far outweighs his focus on his eponymous Denny Day.

As interesting as Day’s story is, it is not the most critical element to the story of the Myall Creek Massacre.

The crimes are the core of that story, and must never play second fiddle to the stories of others. The book that has the courage to begin with the crimes themselves, and not shy away from the scene, will be the definitive Myall Creek Massacre title.

Murder at Myall Creek by Mark Tedeschi (Simon and Schuster) is not that book. It’s an absorbing read but it should probably be re-branded as more of a biography of colonial NSW Attorney General John Plunkett and his impact on the legal system of New South Wales, and less of a broad title on the Myall Creek Massacre.

Murder at Myall Creek by Mark Tedeschi (Simon and Schuster) is not that book. It’s an absorbing read but it should probably be re-branded as more of a biography of colonial NSW Attorney General John Plunkett and his impact on the legal system of New South Wales, and less of a broad title on the Myall Creek Massacre.

What it adds to the record are insights into why Plunkett moved for an immediate second trial of some of the massacre perpetrators, and how the risk paid dividends in terms of a generally just outcome.

Tedeschi makes the case for a better understanding of Plunkett’s character and exactly what he added to Australian civil rights. He also argues for why Plunkett has been largely forgotten by a nation whose history he impacted so significantly.

Elucidating the differences between Colonial and modern Australian legal processes is one of the key aspects to Tedeschi’s work, and this focus is essential to a full understanding of the prosecutions, and several unjust outcomes of the trial.

Day’s is a policeman’s story, Plunkett’s an attorney’s. Both their accounts will become crucial resources for whoever creates an unambiguous, mainstream book on this critical episode of modern Australian history, unfiltered by post-colonial perspectives.

A deeper look at the crimes that were the pivot of both men’s contributions will be key to the meaning and scope of that work. It has the potential to make white Australians see where we have for far too long feared to really look.

© Michael Burge, all rights reserved.

Share this: