Here at Fourth & Sycamore, we love to promote the works of up-and-coming writers as well as publications by small presses. So when we meet an author whose writing fits this criteria, we just can’t help but share.

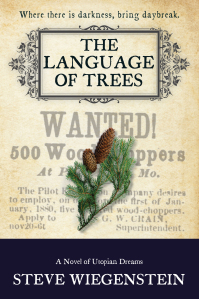

Enter Steve Wiegenstein. If you are a fan of historical fiction, especially that set in the Midwest, then Steve’s work should be on your radar. He has been gracious enough to share with us an excerpt from his upcoming novel, The Language of Trees.

Enter Steve Wiegenstein. If you are a fan of historical fiction, especially that set in the Midwest, then Steve’s work should be on your radar. He has been gracious enough to share with us an excerpt from his upcoming novel, The Language of Trees.

Rather than us go on and on about how wonderful Steve’s writing is, and why you should read his series of novels, we’ll just let the work speak for itself.

And who better to set the scene for us than the author himself! This is what Steve had to say about The Language of Trees and the excerpt you are about to read:

The novel, which will come out on September 26, is an exploration of love, lust, economics, and the environment in a rural 19th century American setting. The inhabitants of a quiet utopian community in the Missouri Ozarks have their ideals tested when a large lumber and mining company comes to make them a hefty offer on their land, and subsequent personal entanglements further complicate the matter. This excerpt is an early chapter of the novel.

The Language of Trees is the third in a series of books set in the same utopian community, known as Daybreak. The first novel, Slant of Light, followed the community from its founding into the Civil War, and the second novel, This Old World, brought it into the Reconstruction era. Slant of Light was the runner-up for the David J. Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction in 2012, and This Old World was a shortlisted finalist for the M.M. Bennetts Award in Historical Fiction in 2014.

In addition to sharing a preview of The Language of Trees, Steve was kind enough to answer some questions about himself and his writing.

We hope you enjoy!

From The Language of Trees

From The Language of Trees

By Steve Wiegenstein

(Blank Slate Press, 2017)

December 1887

J. M. Bridges had never imagined himself running a timber operation in the backwoods of Missouri, or anywhere else for that matter. He had never envisioned himself a captain of industry. He believed, rather, that he was simply a man whose diligence and attention to detail left no doubt about his trustworthiness, a man who could be counted on in any circumstance, a man whose loyalty could not be questioned. So when he was summoned to Mr. Crecelius’ office in May, he was pleased at the prospect of recognition, but mildly apprehensive about coming face to face with the great man himself.

True, he had shown initiative during the godawful snow and ice storm a couple of months before, the worst anyone had ever seen, but he didn’t flatter himself. One inspired week would not vault him over the ranks in a company like American Lumber and Minerals.

The March storm had indeed been a test, though. Starting on a Sunday, stinging torrents of rain had chased pedestrians up Broadway. Then overnight the rain changed to ice, then to sleet that rattled the windowpanes, and then by Monday’s sunrise to snow—heavy, blowing, whistling snow. A foot, a foot and a half, then two feet, drifting in great mounds against buildings, clotting streets into impassibility, and felling the forests of utility poles so that Bridges woke to the snap and sizzle of electric lines as they whipped in the street below.

He knew few men would make it to work that morning and decided to be one of them. He wasn’t sure why. No commerce would take place. That much was clear. But it was a Monday morning, and what one did on a Monday morning was go to work.

The thick, wet snow resting atop the layer of ice conveyed electricity, and Bridges quickly realized that when he got within sixty or seventy feet of a fallen line he felt a tingling sensation that told him to back up and try another route. Others apparently did not possess this ability, and as he trudged through alleys and down sidewalks, he heard the muffled cries of men who had been struck by wires and then more cries from their would-be rescuers. He made it to the building without incident, found it locked, kicked in a side door, and groped his way downstairs to the main power switch. After shutting it off, he had spent the rest of the day—and most of the week—organizing teams to keep the roof cleared, the boiler filled, and the doors barred.

So when he’d arrived at Mr. Crecelius’ outer office in May, it was with the hope of receiving a bonus, and nothing else. He’d paused outside the door to tighten the back buckle on his waistcoat. No one would see whether it was tight, but in Bridges’ mind, the invisibility of his act only added to its need. The snug fit of the waistcoat assured a crisp line to the shoulders of his jacket, and the crisp line of his thrown-back shoulders sent the message he wanted to convey to all who met him, that here was a man to trust.

Bridges’ given name was John Malcolm, but he had settled on “J. M.” after growing dissatisfied with the ordinariness of “John” and rejecting “J. Malcolm” for its pretense. Diligence and trustworthiness were essential, but the first and second floors were full of young men just like himself, earnest strivers who never rose. A man needed a distinguishing mark, and for someone who came from no family to speak of, belonged to no clubs, and possessed no college connections, a distinctive first name would have to do.

Mr. Crecelius’ private secretary was a taut man named Ramsey, with a prematurely receding hairline and a permanent look of ill-concealed impatience. He glanced up but did not speak as Bridges entered.

“I’m Bridges,” he said. “I’m supposed to see Mr. Crecelius at three.”

“I know who you are,” Ramsey replied. “Mr. Crecelius isn’t in. He has a standing appointment after lunch on Wednesdays, and sometimes he doesn’t return at all. Go back to your desk and I’ll send for you when and if he comes in.”

There was a sofa against the wall and a straight chair in the corner. Bridges chose the straight chair so he could see the elevator doors.

“What, you don’t have work to do in the middle of the afternoon?” Ramsey said.

“Nothing that can’t be done after hours. I’ll not waste Mr. Crecelius’ time having a boy fetch me upon his return.”

“I don’t have time for chit-chat with you,” Ramsey said with a grimace. He gestured to a pile of correspondence on his desk.

“Then I’ll not chit-chat,” Bridges said. He folded his hands in his lap.

After half an hour, Ramsey couldn’t stand it. “Where is it you’re from again, young man? New Jersey?” he said, barely glancing up.

Bridges let the “young man” remark pass, although the two appeared to be about the same age. “Delaware. Newark, Delaware.”

“Ah. That explains my New Jersey thought. I remembered that you weren’t a New Yorker.”

Bridges heard the slight in his words but let that pass as well. For all he knew, Mr. Crecelius had given instructions to test his mettle a bit. In any event, there was no point in antagonizing the man who controlled access.

Another twenty minutes passed. “We liked the way you handled yourself in March,” Ramsey said. “You were observed.”

“I’m glad to have been of use,” Bridges said.

Another twenty minutes went by. Perhaps there would be no bonus, but only a certificate for his wall, or a photographed handshake. Mr. Crecelius was renowned for his thrift. That would be a disappointment he would need to brace for and properly disguise.

“I’ve seen his Wednesday appointment,” Ramsey ventured quietly. “I wouldn’t come back to work either.”

Bridges didn’t answer. He had just about had enough of Ramsey’s remarks and smirks.

Then there was a deep groan from the rafters as the cable wheel of the elevator began to turn. Ramsey stiffened and took the next set of papers from his stack, jogging them on his desktop with a nervous clearing of his throat. Bridges stood up.

Mr. Crecelius arrived in a cloud of cigar smoke, ignoring Ramsey, and was about to push his way through to his inner office when he noticed Bridges standing in the corner. He stopped and stared at him blankly.

“This is Mr. Bridges,” Ramsey murmured.

“Ah. Bridges,” said Mr. Crecelius. He strode into his office without another word, leaving Bridges uncertain, until Ramsey waved for him to follow.

Mr. Crecelius had a bright red face and a fierce expression, and the wrinkles of skin from his bald head down his neck made him look like a snapping turtle, if a snapping turtle could grow a bristling white mustache that stuck out from its face as if it was trying to flee to another lip. Bridges stood quietly in the middle of the room while Mr. Crecelius glanced through a stack of letters and papers on his desk.

No one on Bridges’ floor had ever seen this office, though rumors about it flew as regularly as pigeons from windowsills. Bridges vowed not to gawk. He clasped his hands behind his back and studied the room out of the corner of his eye while he waited.

The room was much larger than he’d imagined. On his floor, a room this size would hold forty toiling clerks. There were high curtained windows, a billiards table on one side and what appeared to be a full laboratory on the other, and at the far end a stuffed moose, equally outsized. It felt somewhere between a museum hall and a gymnasium, with a twelve-foot-wide map of the United States on the wall for decoration.

Mr. Crecelius stood abruptly and walked to the map. Bridges followed until he stood next to the great man, who snatched up a long maple pointer and smacked New England. “Cut over.” Then he smacked Pennsylvania. “Cut over.” He smacked the map again. “Can’t build if you have no lumber, and the farther you haul it the costlier it becomes. It’s a simple rule. And that’s why the growth won’t be here.” Smack. “And it won’t be here.” Smack.

Mr. Crecelius didn’t seem to expect comment, so Bridges offered none.

“Here’s where your growth will be.” Mr. Crecelius waved the pointer over a great swath of the midsection of the country. “And here,” he said, circling his pointer over southern Missouri. “Here’s where the trees are.” He stepped closer and felt the map with his hands, as if divining the springs from which wealth would emerge. “Virgin timber, yellow pines eighty feet tall, I’m told. Hundreds of square miles of it.” He traced a line from St. Louis to Little Rock. “And here, a fine little railroad to take it out on. It’s one of Gould’s lines, but we’ll give him his slice.” He bent closer to the map until his nose was almost touching it and placed a finger close to the Arkansas line. “An old boy from Pittsburgh has set up his son-in-law down here, so we won’t go there. Competing for product just drives up the price. No.” He stroked the map with his finger, following the dotted black line as it traveled south from St. Louis, each dot representing a settlement or town. “We’ll go in farther north. Closer to civilization anyway.”

He turned to Bridges and gazed intently into his eyes, his expression almost angry. “I need a man who can talk to people, who can get us into the area and keep the local yokels from greeting us with rope. Mason is a good money man, but he doesn’t rub people right.”

Bridges had no idea who Mason was, but he nodded anyway.

Mr. Crecelius returned to his desk. “It’s a five- to eight-year job, depending on the quality and amount of lumber we pull out of there. That’s why we need a young man like you, unencumbered by wife and family. You are still single, are you not?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Engaged or attached?”

“No, sir.”

He leaned back in his chair. “And your parents?”

“Still living, sir, and in good health.”

“What’s your father do?”

“Saddlemaker, sir.”

For the first time, Mr. Crecelius’ face softened. “Ah,” he said. “Now there’s an honorable old craft.” He paused. “But a dead one. I’ll bet your father doesn’t do half the business he used to. I buy handmade saddles myself, but that’s because I can afford to. Your average Jonathan, he’ll buy a factory-made saddle and learn to live with the poor fit and cheap materials.” His eyes glinted. “Besides, we’re all riding the railway these days.”

He smacked his hands on the desk. “So there it is. You will set up the mill, buy the land, oversee the lumbermen, keep the local folk happy if possible. You will communicate with Ramsey by wire every week at the least, and with me by letter. It’s a thirty-dollar-a-week job if you want it.”

Bridges knew nothing about lumbering. But thirty dollars a week! A more experienced man would have asked for forty, probably, but that was why Mr. Crecelius was rich.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “I want it very much.”

That evening, still dazed from the afternoon’s development as he walked home with a packet of instructions and legal papers under his arm, he stopped by the Leggat Brothers’ bookstore.

“What do you have on Missouri?” he asked the clerk. “I need something about Missouri.”

The clerk scratched his nose. “Missouri. Hm. St. Louis?”

“No, south from there. Out in the countryside.”

The clerk led the way through shelf-lined rooms in the basement. “I saw something in here the other day,” he said. “It’s worn, but still has all its pages. Five cents, and I’ll throw in a copy of Song of Hiawatha.”

Bridges turned the book over in his hands. Scenes and Adventures in the Semi-Alpine Region of the Ozark Mountains of Missouri and Arkansas. “Good heavens, man, this book’s from before the war.”

The clerk shrugged. “Nothing ever changes out there. They probably still shit in the woods.” To Bridges’ dubious look, he added, “All right, take it for a penny. But no Hiawatha.”

“I already own a copy anyway.”

The book had gone into his trunk that night, but now in the hotel in Ironton, with Mason snoring robustly in the next bed, he took it out. They had secured half a section of flat ground beside the railroad tracks a dozen miles south, a perfect place for their mill and the town that would grow up around it. A bright, clear stream ran through it, clearer than New York City tap water. Even a piker like Bridges could tell the quality of the timber that surrounded it, miles and miles in every direction, a carpet of forest over ridgetop and river bottom, riches to be plucked up by the first men in. They already had contracts for ten thousand acres, and that was just the start. Mason might not know how to handle people, but he knew how to handle money, and so far Bridges had learned that the secret to handling people was to find out how much money they wanted and what they were willing to do to get it. And to cap off the week, he’d just caught a glimpse of the prettiest girl he’d ever seen. Her long black hair, pulled back into a twining braid, her deep brown eyes, and her small, sharply contoured nose and lips burned in his recollection like an ember.

He pried apart the stiff pages of the old book, realizing after the first page that the information was even older than the book’s date had led him to believe, that it was a reprint. Waste of a penny. Still, any knowledge was better than no knowledge at all. As he drifted into sleep, he tucked a bookmark into the volume after the preface. He’d try the first chapter in the morning, before he set out to buy more land. Scenes and adventures, indeed. He penciled a checkmark next to the line where he stopped reading for the night: The reading of books of geography makes but a feeble impression on the mind, compared to the actual objects.

Fourth & Sycamore: Thanks for sharing this with us, Steve. Is The Language of Trees the end of the Daybreak series, or can we expect more from this historical utopian town?

Steve Wiegenstein: I’m currently working on the fourth book in the series, which will bring the community into the 20th century, specifically the years 1903-1904. My goal is that each book will be satisfying and self-contained, but also that when you take them as a group, they’ll interlock and create a bigger story, the evolution and transformation of American life through the particular prism of one small Ozarks village. It’s an ambitious project and I hope I can keep all the plates spinning as I move forward; the character histories, family trees, alliances, and enmities keep getting more complicated.

F&S: Where did you get the idea for this series of novels?

Steve: I had long been interested in utopian communities of the 19th century from a scholarly perspective. Utopian communities strike us as strange or foreign, and it’s true that some of them venture into the territory of the weird with their belief systems or particular practices. But from another perspective, utopian communities are the distillation of the American ideal, the idea that the rougher edges of human nature can be mitigated or even resolved by the creation of a superior social structure. So it was a subject that seemed perfect for fiction writing. As a Missourian, and a native of the Ozarks, I wanted to set my work in that region. The Midwest doesn’t get as much attention as it deserves, I think, and the Ozarks are subject to the usual stereotyping as a backward region full of hillbillies who do little beyond making whiskey and acting suspicious toward strangers. There’s a lot more story to be told than just that, so I had the idea of combining my scholarly interest with my regional and creative passions to put together a series of books to tell that story. I started this project in 2007, when the daily news was filled with stories of an occupying American army caught up in savage and unrelenting guerrilla warfare, so naturally that made me think of Missouri during the Civil War. That’s how I chose the time setting for the first book, and since then I’ve been off to the races.

F&S: Can you tell us a little about what’s up next for you?

Steve: I’m hoping to have this series culminate in a novel set in the present day, whenever it is when I reach it. The first few books have had relatively limited time jumps (1857-1865-1887), but the later ones will move ahead several decades at a time. At the moment I’m thinking the series will have six or seven books. After that, I have another, entirely different, book in mind . . . a sort of fable.

F&S: Have you always written historical fiction, or do you dabble in other genres as well?

Steve: Oddly enough, I’d never written historical fiction until I started this novel series! All of my short stories have a contemporary setting. I have usually set them in the Ozarks, though, if they have a specifically designated setting. I have a very difficult time with most fiction set in the Ozarks. Call it homeboy pride, perhaps, but I think we’re more interesting than the fictional portrayals I read. I’m not setting out with the intention of writing a “corrective” or anything like that, but I just see the region as a rich opportunity for portrayal and story-setting.

The same is true of the Midwest, and of rural America in general. There’s an immense vein of wonderful writing about rural life in this country, from Willa Cather and Hamlin Garland on through Jane Hamilton, Wendell Berry, and Jane Smiley, just to name a bare few. But unfortunately writing about rural life is often cubbyholed into a genre label, when to me it is, in some ways, the main stream of American literature. You can’t really appreciate Crevecoeur, Whitman, or Frost without having an in-depth appreciation for the demands and rhythms of rural life.

F&S: Of the Daybreak series, do you have a personal favorite? If not, was one more enjoyable to write than the others?

Steve: I think the latest one, The Language of Trees, is the most polished, and I’d say it’s the most exciting to me in terms of the opening up of possibilities. I put everything I had into Slant of Light; I think all authors have a special place in their hearts for their first books, because that’s the book that shows you that you have what it takes to write a book. But as far as a favorite goes, I’d have to say This Old World. Like middle children everywhere, it’s an underappreciated overachiever, and it’s the novel in which I figured out that to realistically portray the consciousness of an entire community, I’d need to develop a very fluid point of view that moved from character to character, while at the same time, kept an unbroken flow of action going. It’s also the novel in which I discovered that if you put everything into a book, as I did with Slant of Light, you just open up more room for a new set of “everything” to appear.

F&S: Thanks, Steve! We wish you the best with this novel and all those yet to come!

For more on Steve Wiegenstein, and how to purchase his novels, go to www.stevewiegenstein.com

Share this: