Cornelius Ryan Joins Exclusive Company

By Jeff Salter

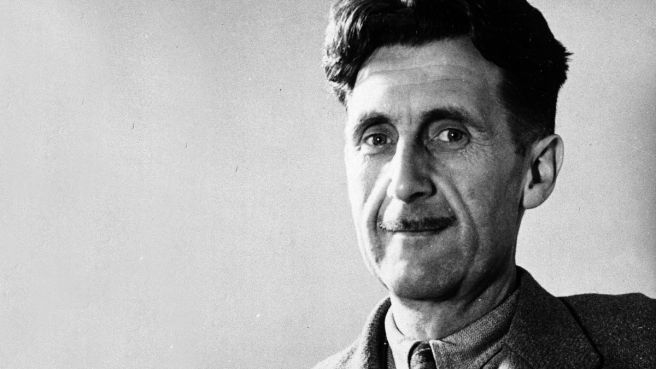

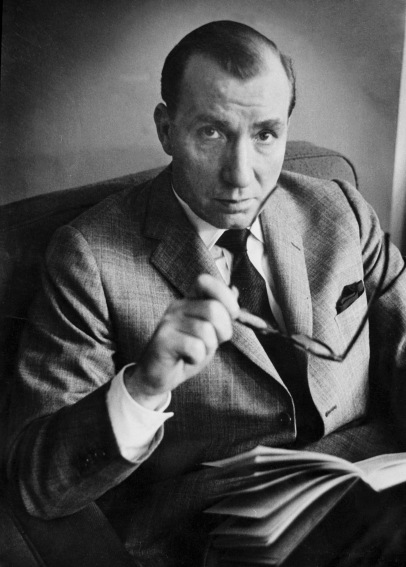

On these pages, I’ve previously highlighted the remarkable Rick Atkinson (author of the Liberation Trilogy) and I believe I’ve mentioned Stephen Ambrose (most famous for Band of Brothers but my favorite is Pegasus Bridge). Atkinson and Ambrose are indeed at the very pinnacle of my list of fine authors of WW2 non-fiction… and to their elite group I now add Cornelius Ryan. [Note: within the realm of WW2 FICTION, my clear favorite is Jeff Shaara.]

Bless his heart, Ryan died over 42 years ago (1974) and for most of this time I knew him only as the author of two war books which were converted into excellent war movies. I’ve seen each movie many times over. These are, of course, The Longest Day and A Bridge Too Far. But I had never taken the time to read the books themselves… and what a treat I’ve been missing.

Let me begin with a little biographical capsule of Ryan, born in 1920 in Dublin. He was inspired to write by his favorite English teacher, Frank MacManus. As a youngster, Ryan played the violin; as a young adult he worked at Collinstown Airport and dabbled in amateur theater.

By his early 20s, Ryan was already a war correspondent. Initially covering the air war in Europe, Ryan flew along on fourteen American bombing missions. He then joined Patton’s Third Army and covered its actions until the end of the European war. He transferred to the Pacific theater in 1945.

According to Wiki: “On a trip to Normandy in 1949 Ryan became interested in telling a more complete story of Operation Overlord than had been produced to date. He began compiling information and conducting over 1000 interviews as he gathered stories from both the Allies and the Germans, as well as the French civilians. In 1956 he began to write down his World War II notes for The Longest Day: 6 June 1944 D-Day, which tells the story of the D-Day invasion of Normandy, published three years later in 1959.”

Along the way becoming a friend of President John F. Kennedy, Ryan published three best-selling books before his cancer death at 54.

A Bridge Too Far is the book I’m just now finishing.

Says an Amazon review: it’s the “masterly chronicle of the Battle of Arnhem, which marshaled the greatest armada of troop-carrying aircraft ever assembled and cost the Allies nearly twice as many casualties as D-Day. In this compelling work of history, Ryan narrates the Allied effort to end the war in Europe in 1944 by dropping the combined airborne forces of the American and British armies behind German lines to capture the crucial bridge across the Rhine at Arnhem. Focusing on a vast cast of characters — from Dutch civilians to British and American strategists to common soldiers and commanders — Ryan brings to life one of the most daring and ill-fated operations of the war. A Bridge Too Far superbly recreates the terror and suspense, the heroism and tragedy of this epic operation, which ended in bitter defeat for the Allies.”

Wiki states: “The Allies had failed to cross the Rhine and the river remained a barrier to their advance into Germany until offensives at Remagen, Oppenheim, Rees, and Wesel in March 1945. The failure of Market Garden to form a foothold over the Rhine ended Allied expectations of finishing the war by Christmas 1944.”

My analysis

What has impressed me about Ryan’s account is the futility of a poorly planned mission: on one hand, the courage, sacrifice, and endurance of the troops committed to battle and the civilians caught in the crossfire. On the other hand, the apparently casual acceptance (by higher-ups) of every setback and a seeming willingness to forsake the military and civilians in harm’s way. It was a terrible plan that Montgomery wanted and almost nobody else cared for. But, as he often did, Monty got his way. Too hasty, too incomplete, too optimistic, too short-sighted. The planners lacked information on the enemy strength and the Dutch terrain, they refused to believe info and intel from the Dutch civilians and refused to accept assistance from the Dutch underground.

Pinning all their hopes on the element of surprise, the Allies experienced more surprises than the Germans did. Among the huge failures were the poorly functioning radio sets, the lack of coordination among airborne units (two American, one British, and one Polish), between airborne units and the ground elements, and between all units and their own HQ. Not to mention poor coordination and communication between the distant planners/overseers and the air forces (back in England) who would deliver parachutists, gliders, supplies, and would provide bombing and strafing missions.

To put it succinctly, hardly anyone could communicate directly with anyone they needed to reach in real time. What little info that moved at all, was fragmented and woefully out-of-date. Vitally needed supplies landed more in enemy territory than among the Allies desperately waiting. The weather in England delayed or cancelled flights of reinforcements, supplies, and attack support missions. The Horrocks vanguard of tanks and armored vehicles – confined to a single highway barely sufficient for ordinary traffic – spent most of the nine-day battle bottled up and unable to advance. That left the valiant airborne divisions scrambling and sacrificing to hold their objectives for the relief that never came.

Initially overjoyed at the sight of Allied parachutes and gliders, Dutch civilians naturally assumed Allied ground troops were on the way immediately. Indeed, the Allies could have exploited the surprised Germans if they’d acted quickly — but everything bogged down.

Expecting “liberation” (from German occupation) by the Allies, instead the Dutch faced reprisals and months of deprivation and suffering. Many Dutch cites were reduced to rubble; many civilians were left without homes, property, and food. Market Garden was a dismal defeat both for the Allies and the innocent civilians who happened to be caught between two warring enemies.

Just a quick word about Ryan’s other major book, which “endures as a masterpiece of living history” (says an Amazon reviewer). I finally read this one a few months ago.

Look at what Robert McNamara has to say about it: “A true classic of World War II history, The Longest Day tells the story of the massive Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. Journalist Cornelius Ryan began working on the book in the mid-1950s, while the memories of the D-day participants were still fresh, and he spent three years interviewing D-day survivors in the United States and Europe. * * * Ryan was enormously skillful at weaving small personal stories into the overall narrative * * *. [S]ubsequent historians, dutifully noting its accuracy, have relied heavily on Ryan’s research for their own accounts.”

My Final Word

I may not be able to back this up, but it’s my impression (having read numerous books on WW2) that – prior to Ryan’s 1959 epic – most authors writing on battles and campaigns went solely to the official sources, including the published accounts of generals, public officials, and formal historians. Of course, Ryan also mined those sources exhaustively. But as I see it, Ryan shook things up by additionally interviewing soldiers, airmen, sailors – up and down the ranks – on BOTH sides… as well as civilians in the affected areas. Many of the military histories (prior to Ryan’s 1959 masterpiece) read almost like a detailed account of a chess match — where the decisions were analyzed and the results dissected, but the humanity was overlooked. In Ryan’s accounts, you can feel the tension, fear, pain, hope, despair, and (yes) even humor at times. Without Ryan’s successful approach, I wonder if Ambrose would have hit his stride. Without Ryan and Ambrose, I wonder if Atkinson would have discovered both voice and audience.

My hat’s off to my new buddy, the late Cornelius Ryan.

[JLS # 320]

Advertisements Share this:- More