I first discovered Zebedy Colt in early 2002, at Mondo Video back when it was located on Vermont just north of Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles’s rapidly-gentrifying Los Feliz. It wasn’t Colt who drew me to Farmer’s Daughters, but rather the mind-blowing (to me, at least) presence of Spalding Gray in a particularly grimy-looking hardcore film.

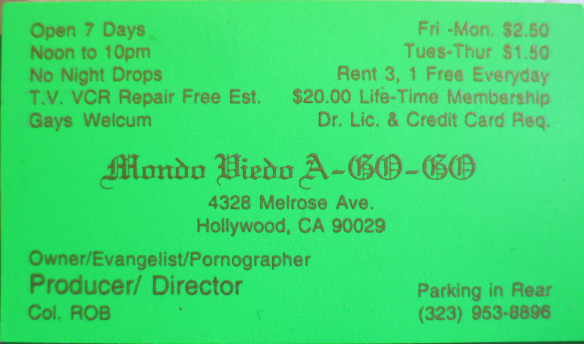

Alas: this was before easy streaming or downloading of movies, and some rat bastard kept the tape checked out so long that I had moved into the neighborhood, right across the street, but Mondo Video then moved out (after its transgender mud-wrestling matches on the rooftop and huge poster of Osama bin Laden sodomizing George W. Bush in the front window apparently violated both the terms of its lease and the increasingly hip-genteel community standards), to a stretch of Melrose Avenue far east of anything Aaron Spelling ever put on TV, before I ever saw Farmer’s Daughters.

Aside from the uncanny presence of my favorite monologue-artist, the film itself was mostly boilerplate, queasily misogynistic porn with an emphasis on rape. I didn’t like it, or ideologically approve of it, but I was curious about it—who were these depraved goons shooting this unhinged filth? From this unseemly origin would emerge a decade-plus fascination with the filmmaker of Farmers Daughters, Zebedy Colt.

At the time, sources were few and far between. As I recall it, this was slightly before the boom years for cult-movie discussion boards, which I’d date as roughly 2004 to 2010, or whenever it was that Facebook sucked the life out of the entire internet (to see its pernicious effects on online communities, wander the virtual ghost town of the once-thriving AVManiacs forums sometime, and weep). Michelle Clifford’s Metasex zine offered one breakthrough, with a lengthy profile of Colt. Clifford and her partner, Sleazoid Express founder Bill Landis, were pioneers in grindhouse journalism, but frequently criticized for lapses in accuracy, so it’s hard to separate the apocryphal from the true at times (did young Edward Earle—Colt’s legal name—really attend college with Kenneth Anger and Curtis Harrington? I have no idea, but it sounds a little too good to be true…). Still, it was something.

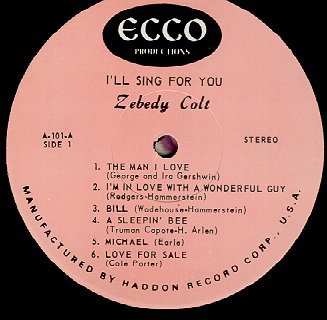

A real breakthrough came with the publication of the September 2004 edition of Queer Music Heritage, JD Doyle’s long running and award winning digital history project. Unearthing a rich set of documents (seriously: do not fail to click that link!) chronicling Zebedy Colt’s emergence as a gay liberationist singer-songwriter in the late 1960s, Doyle radically reframed the story—smut came as an afterthought to a broadly ambitious attempt at queer cultural activism.

By this point, I’d been watching and contemplating Colt’s films for a few years. The Devil Inside Her (1976), Virgin Dreams (1977), and such acting roles as his confused serial rapist/killer in Sex Wish (1976) all reflected various queer flourishes, and Colt as director showed an obvious and undeniable interest in the male body. Nothing was hidden or secret here: acting in Gerard Damiano’s Story of Joanna (1975), he blew Jamie Gillis! And in his own magnum opus Unwilling Lovers (1977), he again depicted explicit male/male sexual contact, in the context of an ostensibly (if only by default) heterosexual hardcore film. But it was only with Doyle’s piece that I began to think about Colt through a scholarly lens—this was a queer intervention that had gone effectively unrecognized, even as porn studies exploded in the early 21st century.

Indeed, while every member of online fan communities (mostly populated by straight men who were vastly more comfortable with queerness than feminism, in my experience) knew that a huge swath of the men who populated hetero hardcore in the 1970s on both sides of the camera fell somewhere outside a rigid heterosexuality, from Marc Stevens to Jamie Gillis to the Amero Brothers to Chuck Vincent to John Holmes and on and on and on, porn studies scholars rarely reflected this in their analyses. Only Jake Gerli’s article on Vincent, in the 2004 Porn Studies collection edited by Linda Williams, engaged with this fact. And I found Gerli’s article a mixed bag: smart in its analysis, and prescient in pointing toward further work, but limited in its engagement with a very selective set of Vincent’s large body of work, which is then given a queer reading that would be hard to extend to many of his films, which resist the problematizing of heterosexuality upon which Gerli mounts much of his case—Bad Penny and MisBehavin’, for instance, have none of the ambivalence of Roommates or In Love—while meanwhile even a cursory glance at the often melancholy work of straight directors such as Shaun Costello, Anthony Spinelli, Roberta Findlay, or even Gerard Damiano shows that by the late 1970s, heterosexuality may have exhausted itself wholly, thus undermining Gerli’s queer reading of Vincent a bit.

So, I sat with this for a few years. And then I had a bad year, moving to Miami for a short-term appointment, commuting monthly to L.A. in a failing effort to keep a long-distance relationship afloat, and ultimately winding up back on my couch in Silver Lake, making less than enough to cover the rent adjuncting and fairly hopeless about both my personal and professional life. Channeling some of that frustration into scholarly work, I pitched a paper about Colt to the Popular Culture Association conference, which was meeting in San Francisco in 2008. To my surprise, it was accepted.

Broke as hell, I took a cheap LAX->SFO flight up for the panel, and flew back the same day to save on a hotel. The paper went pretty well, albeit to an audience of about three. And then . . . nothing. Life got chaotic, and Zebedy Colt went on the backburner. I took a job in Philly. The relationship finally fizzled out. I spent time feeling sorry for myself. I landed a book contract. I got a new job in Newark. New and better relationships took shape. I wrote a second book. Etc.

All along, I kept waiting for someone to come along and scoop me by publishing something similar, but it never happened. And after losing interest in porn studies for some years, I wandered back into the field. I tend to keep too many projects in the air, making it hard to return to something that’s been dormant for so long, but finally around 2015 I said to hell with it, I’m returning to my dear old Zeb.

To make a long story short, I polished and expanded my old conference paper, updating it with recent scholarship in porn studies and queer theory. Academic publishing is something of a nightmare: it moves incredibly slowly, and peer reviews can be ridiculously arbitrary, so if you send a piece to the wrong journal, you can lose a year with nothing to show for it (and while rejection is part of the game, some places can be obnoxious about it—I’m looking at you, Religion and American Culture, which rejected a submission once after losing track of it for several months, belatedly sending it out for review, and then refusing to share the reviews or even respond to a polite follow-up inquiry; poor form!). But I was in the admittedly privileged position of having low stakes (I didn’t need this for tenure), so I aimed high: GLQ, the pioneering queer studies journal. Mostly I figured, why not, the thing’s already been on the backburner nearly a decade, what’s another year?

The basic gist of the article manuscript was threefold: first, porn scholars and queer scholars alike have overlooked the presence of Zebedy Colt and other queer filmmakers and performers in the hetero hardcore world, partly because the available archives used for research skew toward a somewhat sanitized mainstream canon; yet, Colt and others complicate the ostensibly straightforward heterosexuality even of smut, seemingly a bastion of the normative male gaze; and finally, while there is much that is perverse and transgressive here, ultimately Colt leverages both misogyny and whiteness to secure the straightness of his films, their homoeroticism effectively absorbed into a larger structure of heteronormativity that doesn’t singularly rest on heterosexuality alone.

On first round, I received a timely and encouraging revise & resubmit; the reviews were rigorous and wanted some serious overhauls (including making use of the just-published Not Gay by Jane Ward), but they were genuinely constructive, in a way you see far too infrequently in these circumstances (a push for me to discuss the state of porn archives was really music to my ears, and led to a whole new section that became part of the subtitle). So I poured some serious thought and labor into it, sent a modified version back, and waited—and, on another eminently reasonable timeline, I received the exciting news that the article had been accepted (with a few more modest revisions). So, kudos to GLQ editor Elizabeth Freeman for running a tight ship over there (and for bringing to my attention the wonderful but perversely overlooked sort-of-New-Queer-Cinema gem The Sticky Fingers of Time in her great book Time Binds—see cat scenes here, BTW).

So, that’s the story behind “Sex Wishes and Virgin Dreams: Zebedy Colt’s Reactionary Queer Heterosmut and the Elusive Porn Archive,” which appears in this month’s GLQ. I’m happy to share a pdf with anyone who’d like to read it, and I’m going to follow this post up with some outtakes from the article that were cut for wordcount but seem interesting at a historical level.

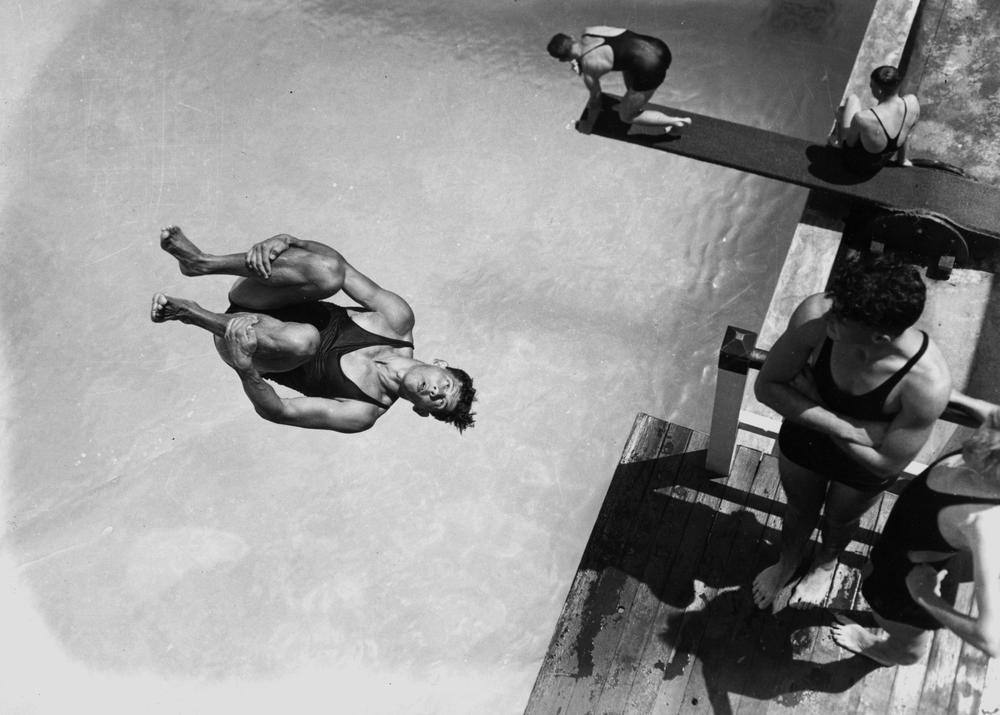

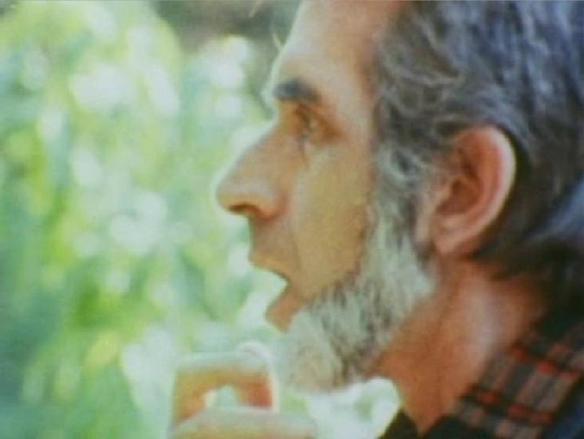

also, photo outtakes:

and finally, a history of erasure in Los Angeles, 2007-2010:

Advertisements Share this: