OK, this New Title Tuesday recommendation, So Much Blue by Percival Everett, is an absolute must-read! It’s one part modern-midlife crisis, one part funny social commentary on class and academia, one part secret-solving, and one part thrill-ride in El Salvador of 1979.

Publisher’s Summary: Kevin Pace is working on a painting that he won’t allow anyone to see: not his children, not his best friend Richard, not even his wife, Linda. The painting is a canvas of twelve feet by twenty-one feet (and three inches) that is covered entirely in shades of blue. It may be his masterpiece or it may not; he doesn’t know or more accurately doesn’t care.

What Kevin does care about are the events of the past. Ten years ago he had an affair with a young watercolorist in Paris. Kevin relates this event with a dispassionate air, even a bit of puzzlement. It’s not clear to him why he had the affair, but he can’t let it go. In the more distant past of the late seventies, Kevin and Richard traveled to El Salvador on the verge of war to retrieve Richard’s drug-dealing brother, who had gone missing without explanation. As the events of the past intersect with the present, Kevin struggles to justify the sacrifices he’s made for his art and the secrets he’s kept from his wife.

So Much Blue features Percival Everett at his best, and his deadpan humor and insightful commentary about the artistic life culminate in a brilliantly readable new novel.

So Much Blue begins with some learned ideas about dimensions and the concept of names that gave me pause. For example, on the first page, Everett’s protagonist, Kevin Pace, admits that he doesn’t understand what his mathematician friend meant by “dimensions of an object are independent of the space in which that object is embedded.” (I am on the record mumbling, huh?)

However, this introduction to Kevin Pace demonstrates the totality of the character – cerebral successful artist, husband and father, and the someone who would bring “a bicycle chain to a fight in an alley at two in the morning” for a friend.

The friend he speaks of is Richard, who has promised Kevin to protect his secret painting and “will burn the studio to the ground” if Kevin should die before him. Kevin continues, “I believe he will be faithful to this promise, but sadly I doubt that he will outlive me. And so I have a plan to booby-trap the place…. It’s not that I don’t trust Richard, it’s that I do not trust traffic. I do not trust weather. I do not trust lines of communication fiber optics and microwaves notwithstanding. Neither do I trust automobiles, especially those without carburetors. Richard might be on vacation or flirting with a woman he’s met on the village square when I dies of a sudden. Mobile reception might be lost because of a lightning strike to a tower. It could happen.”

As Walton Muyumba said in his LA Times review, “Pace’s storytelling is more like a three-suit deck of cards shuffled so that a card from each suit appears alternately, each card its own short story. With 25 books of fiction and poetry to his name, Everett doesn’t have the broad audience his writing deserves. Nonetheless, among his fans, he has a reputation for writing humorous, philosophical, innovative and formally challenging works such as Erasure (2000), I Am Not Sidney Poitier (2009) and Percival Everett by Virgil Russell (2013).”

NPR’s Michael Schaub also said, So Much Blue is “a generous, thrilling book by a man who might well be America’s most under-recognized literary master, and readers will be thinking about it long after the last page.”

I know that I am going to get my hands on at least one more of his almost thirty books. Do yourself a favor and check out Everett’s So Much Blue.

Happy reading, Susan C.

Also By Everett:

Percival Everett by Virgil Russell – A Novel

A story inside a story inside a story. A man visits his aging father in a nursing home, where his father writes the novel he imagines his son would write. Or is it the novel that the son imagines his father would imagine, if he were to imagine the kind of novel the son would write? Let’s simplify: a woman seeks an apprenticeship with a painter, claiming to be his long-lost daughter. A contractor-for-hire named Murphy can’t distinguish between the two brothers who employ him. And in Murphy’s troubled dreams, Nat Turner imagines the life of William Styron. These narratives twist together with anecdotes from the nursing home, each building on the other until they crest in a wild, outlandish excursion of the inmates led by the father. Anchoring these shifting plotlines is a running commentary between father and son that sheds doubt on the truthfulness of each story. Because, after all, what narrator can we ever trust? Not only is Percival Everett by Virgil Russell a powerful, compassionate meditation on old age and its humiliations, it is an ingenious culmination of Everett’s recurring preoccupations. All of his prior work, his metaphysical and philosophical inquiries, his investigations into the nature of narrative, have led to this masterful book. Percival Everett has never been more cunning, more brilliant and subversive, than he is in this, his most important and elusive novel to date.

I Am Not Sidney Poitier

I was, in life, to be a gambler, a risk-taker, a swashbuckler, a knight. I accepted, then and there, my place in the world. I was a fighter of windmills. I was a chaser of whales. I was Not Sidney Poitier.

Not Sidney Poitier is an amiable young man in an absurd country. The sudden death of his mother orphans him at age eleven, leaving him with an unfortunate name, an uncanny resemblance to the famous actor, and, perhaps more fortunate, a staggering number of shares in the Turner Broadcasting Corporation.

Percival Everett’s hilarious new novel follows Not Sidney’s tumultuous life, as the social hierarchy scrambles to balance his skin color with his fabulous wealth. Maturing under the less-than watchful eye of his adopted foster father, Ted Turner, Not gets arrested in rural Georgia for driving while black, sparks a dinnertable explosion at the home of his manipulative girlfriend, and sleuths a murder case in Smut Eye, Alabama, all while navigating the recurrent communication problem: “What’s your name?” a kid would ask. “Not Sidney,” I would say. “Okay, then what is it?”

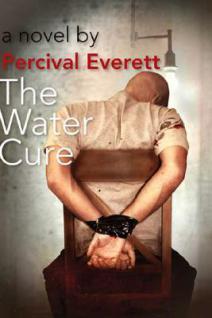

The Water Cure

“I am guilty not because of my actions, to which I freely admit, but for my accession, admission, confession that I executed these actions with not only deliberation and premeditation but with zeal and paroxysm and purpose. The true answer to your question is shorter than the lie. Did you? I did.”

This is a confession of a victim turned villain. When Ishmael Kidder’s 11-year-old daughter is brutally murdered, it stands to reason that he must take revenge by any means necessary. The punishment is carried out without guilt, and with the usual equipment—duct tape, rope, and super glue. But the tools of psychological torture prove to be the most devastating of all.

Everett’s most lacerating satire to date, Other Languages Are All We Have, follows the gruesome reasoning and execution of revenge in a society that has lost a common moral ground, where rules are meaningless. A master storyteller, Everett draws upon disparate elements of western philosophy, language theory, and military intelligence reports to create a terrifying story of loss, anger, and helplessness in our modern world. This is a timely and important novel that confronts the dark legacy of the Bush years and the state of America today.

Wounded Training horses is dangerous—a head-to-head confrontation with 1,000 pounds of muscle and little sense takes courage, but more importantly patience and smarts. It is these same qualities that allow John and his uncle Gus to live in the beautiful high desert of Wyoming. A black horse trainer is a curiosity, at the very least, but a familiar curiosity in these parts. It is the brutal murder of a young gay man however, that pushes this small community to the teetering edge of intolerance.

Highly praised for his storytelling and ability to address the toughest issues of our time with humor, grace, and originality, Everett offers a brilliant novel that explores the alarming consequences of hatred in a divided America

Share this: