Books bought:

Books bought:

- Unconditional Surrender, Evelyn Waugh

- Officers and Gentlemen, Evelyn Waugh

- Black Mischief, Evelyn Waugh

- Before We Were Yours, Lisa Wingate

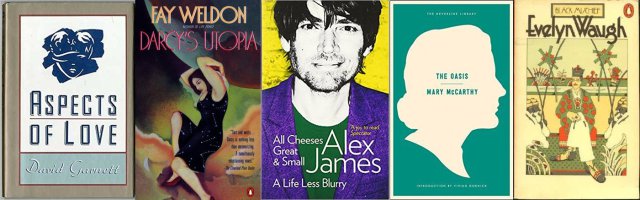

- Aspects of Love, David Garnett

- Darcy’s Utopia, Fay Weldon

- All Cheeses Great and Small: A Life Less Blurry, Alex James

- The Oasis, Mary McCarthy

- Black Mischief, Evelyn Waugh

- Words and Names, Ernest Weekley

David Garnett was in the middle of the most salacious bit of Bloomsbury gossip, already discussed here but always worth revisiting: Garnett (son of prolific translator of Russian literature Constance Garnett and I guess also respected critic Edward Garnett) lived on a farm with Duncan Grant (cousin of Lytton Strachey and also at one point lover of Lytton Strachey, among others) and Vanessa Bell (sister of Virginia Woolf) during WWI. Grant and Garnett were lovers during this period, but Bell was also in love with Grant, and, despite Grant being mostly gay, they had a daughter, Angelica, who grew up believing that Vanessa’s actual husband, Clive Bell, is her father. Fast-forward about 20 years and Angelica loses her virginity to Garnett–remember, her biological father’s former lover–in H.G. Wells’s spare bedroom; they married a few years later and had four daughters together.

So what sort of fiction does that produce? Well, the plot of Garnett’s Aspects of Love, inasmuch as there is a plot and not just, like, a series of increasingly scandalous pairings:

Alexis, a young Englishman abroad, falls in love with Rose, a French actress; they have a short but passionate affair in Alexis’s uncle’s country house. Rose then meets the uncle, George, and ends up marrying him and having a daughter, Jenny. Alexis is very close with Jenny as she grows up and by the time she hits 13, it becomes clear that feelings have emerged on both sides (eww) . George sees Alexis going up to Jenny’s bedroom, has a heart attack, and dies. At the funeral, Alexis meets Giulietta, George’s Italian lover, and ends up pursuing a relationship with her to avoid acting on his feelings for Jenny (thank god). The end.

Given the obvious ties to Garnett’s actual life, I just have no idea how to read this. So there’s this passage, when Alexis first discovers Rose has married his uncle:

“If she comes in now I shall shoot her,” he whispered. And then almost immediately added: “Am I mad or sane? Do I feel what I imagine I feel, or am I an automaton?” He became aware that he was in pain and had been in pain for some time past and that he was grinding his teeth.

He felt ashamed of doing so and at once stopped.

“Je m’en fous de la psychologie,” he said aloud.

And man, I hope this is meant to be a parody of Dostoevsky or something, because if not, it is just too ridiculous. The whole novella, in fact, would seem too ridiculous to be read straight, if not for the autobiographical aspect. And if it isn’t a satire, then every new romantic entanglement introduced takes the tone of Garnett being like, “Hey reader, are you shocked yet? Is this too taboo for your petit bourgeois sensibilities?”

Apparently, there’s an Andrew Lloyd Webber musical adapted from this, which: what? Why? How? But it did result in this delightful Forbidden Broadway parody.

I picked up Darcy’s Utopia at The Last Bookstore in LA a few years ago, because I really enjoyed Fay Weldon’s Female Friends. I…did not connect with this one as much, and I’m not even sure what there was to connect with.

I think I saw Alex James talking about cheese-making on Never Mind the Buzzcocks before I was really aware of Blur being a Thing, but now I fucking love Blur (yes, v late to the game) and also have romantic visions of English country life, so it seemed like a good time to check out James’s memoir about his post-Blur life on a farm. All Cheeses Great and Small maybe isn’t super noteworthy if you don’t care about Blur-or even if you do, since it doesn’t even mention Blur that much–but it is a basically charming and pleasant read and an interesting look into a semi-unusual lifestyle.

The Oasis was definitely not the right book to read on a plane, oops. I guess there’s a legitimate reason people read airport thrillers on airplane and not anything “deeper.” It’s a pretty short book and basically every sentence feels very intentional, if that makes sense–there’s nothing that’s just there to move things along, since it’s less focused on plot than on satirizing various personalities/ideas/movements. From Vivian Gornick’s introduction:

And there we have the brilliant and quite original thesis of The Oasis: the people of the ideological left–intellectual and plebeians alike–imagine themselves moralists of the first order, when they are in fact possessed of only B-plus morality. In the hands of an Edmund Wilson this thesis might have invoked a sense of tragedy; in the hands of Philip Rahv himself, unmitigated scorn; with Mary McCarthy it becomes an instrument of contemplative ridicule–perhaps the unkindest cut of them all.

McCarthy’s language really does deserve more attention than I was able to provide, so I’ll probably revisit this at some point. On a super shallow note, the Neversink Library editions are so aesthetically pleasing that the simple fact that a book is in that collection is going to increase my chance of reading it, so I guess: mission accomplished, Melville House.

The quest to complete Evelyn Waugh’s novelistic output by the end of 2017 continues with Black Mischief, a pretty embarrassing book to be seen with in public. It’s not as racist as you would expect from the title? But yeah, the portrayal of—well, basically anyone not white—is often an uncomfortable aspect of Waugh’s novels to the 21st century reader. There’s still some solid satire of the English upper classes in there, and I guess this is what Basil Seal was up to pre-Put Out More Flags.

E.M. Forster recommended Words and Names in one of his BBC talks (21 November 1932) and yay, etymology! As per usual, EMF is dead-on. This book in particular is focused on words derived from names; some of them are pretty obvious (quixotic, tantalizing, Sisyphean, etc.), but still plenty of fun facts to be had. A sample:

- Maybe this is also obvious, but it was news to me: “From [Venus] is formed the verb venerari, to adore, cherish, so that the adjectives venerable and venereal go back to a common source.”

- Debunk is from bunkum, which is in turn from an incident involving a congressman from Buncombe County, North Carolina

- Of particular interest to anyone who grew up in Virginia and was weirded out by the existence of a city called Lynchburg—Lynchburg is named for its founder, John Lynch (1740-1820), while the verb to lynch is probably from his brother, Charles Lynch (1736-1796).

- I’m still obsessed with Cockaigne, after years of seeing it in Joy of Cooking and making the obvious Cockaigne-cocaine jokes (cocaine has a completely different etymology, though), and this makes it even better: “The land of Cockaigne, an imaginary region of ease and plenty, is from French Cocagne (12th century). It has been conjecturally derived from German kuchen, cake.” How appropriate!

This definitely didn’t help with the linguistic crisis I’ve been having over our Boggle house rules lately (very strict wrt slang, archaisms, abbreviations, etc.) because, like, what even is a proper noun? What even is language, mannn?

Selected quotes:All Cheeses Great and Small: A Life Less Blurry, Alex James

I even started liking Beethoven. Actually, I made it happen, same way as I made myself like oysters: perseverance. I decided to listen to his First Symphony every day for ten days at high volume and see what happened. Around about the seventh or eighth day the thing was permanently playing in my head. As I wandered around the place, the entire English countryside transformed in my mind into a monster budget video commissioned specifically to accompany his music. I was inside a perfect film hearing imaginary violins and oboes, beguiled—sometimes to a standstill—by the excellence and variety of the colour green or the exactness of sunshine on alliums, with their subtle garnish of sheep in the middle distance and a host of imaginary violins.

The Oasis, Mary McCarthy

Tall, red-bearded, gregarious, susceptible to a liver complaint, puritanical, disputatious, hard-working, monogamous, a good father and a good friend, he had suffered all his life from a vague sense that he was somehow crass, that he did not belong by natural endowment to that world of the spirit which his intellect told him was the highest habitation of man. That he could not see this world was a source of perpetual grievance to him; he knew that it existed through perceiving its effect on others, as a man in a snug house infers that the wind is blowing from the agitation of the leaves on the trees. Had he not seen a poem, he would have scoffed at the idea of poetry, and had the idea of poetry not been presented to him, he would have scoffed at a poem. Nevertheless, ten years before, he had made a leap into faith and sacrificed $20,000 a year and a secure career as a paid journalist for the intangible values that eluded his empirical grasp. He had moved down town into Bohemia, painted his walls indigo, dropped the use of capital letters and the practice of wearing a vest, and, having thus impressed his Sancho Panza into the service of quixotic causes, he now felt it to be the keenest ingratitude that he should be asked to admit into the fellowship a man who had done nothing.

Black Mischief, Evelyn Waugh

Advertisements Share this:‘I wonder where they keep the Evian.’

They went into the bar. Alcohol everywhere, but no water. In a corner of the kitchen they found a dozen or so bottles bearing the labels of various mineral waters—Evian, St Galmiet, Vichy, Malvern—all empty. It was Mr Youkoumian’s practice to replenish them, when required, from the foetid well at the back of the house.