Golden turns on the ice age. Andrews Glacier, RMNP

Since returning from the trail I’ve felt an increased desire to learn about mountain ecology. More specifically, I’m fascinated by that dying thing known as the mountain glacier. In Glacier National Park where we finished our hike, the forecast is that they will all be gone by 2030, melted away as part of human-caused global warming. Before departing, we took a walk up to the famous Grinnell Glacier, and while I have no personal previous experience to compare it to, the reaction from Elaine and her parents left it painfully evident that it has shrunk a lot since they first saw it 15 years ago.

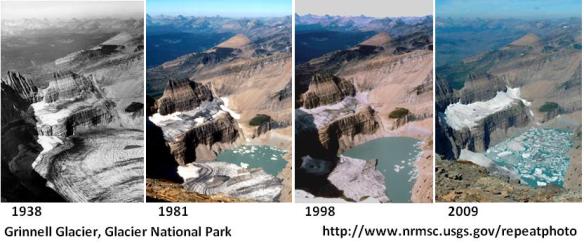

Grinnell Glacier in Glacier National Park, Montana – September 29, 2017. Below are images of Grinnell Glacier over the past 80 years. Note how the upper and lower glaciers connected and the lake was entirely a glacier in 1938.

Upon leaving the park, I picked up a copy of Christopher White’s book “The Melting World,” and spent the next 30 hours in the back seat absorbing myself in the dire news. It’s a somber read, but it does make me want to something. I’m not a scientist of glaciologist, but I can explore places and share them with others on an emotional level, leaving the data and figuring to those much more advanced in such things.

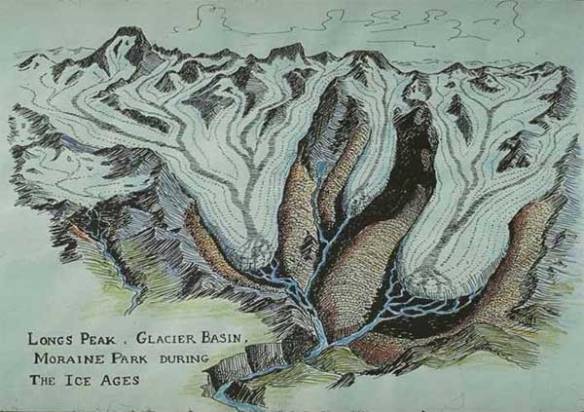

16,000 years ago the Indian Peaks and Rocky Mountain National Park looked like this. Mastodons and Woolly Mammoths roamed the land.

My wife and I are fortunate to live in the only part of Colorado where there actually are glaciers. The largest, Arapaho Glacier, is about four miles as the crow flies from our back door. This is not a glacier you can legally tread on, as it is part of the closed-to-the-public City of Boulder Watershed. Fortunately there are other nearby glaciers, the closest being Isabelle Glacier under the shadow of Apache Peak.

In Rocky Mountain Park, just north of us, there are even more of these mountain glaciers. Tyndall, Sprague, Rowe and Taylor Glaciers are a few of the more famous ones. But for Elaine and I, Andrews Glacier, just east of the Continental Divide, is our glacier of habit and annual visit. We’ve been coming here for years in late fall, seeking the glacier for ski turns. Our monthly ski streak relies on these glaciers. Like an old friend, we visit Andrews each autumn to catch up, have fun and assess where we are in our respective worlds, human and glacier.

It’s not so much about the actual skiing. In this 13-mile roundtrip hike, there are maybe 500 yards of actual turns. Year round skiing is more about the experience, less about the turns, especially in the latter months August, September and early October. Andrews has everything a year-round skier could want: predictable snow coverage, an easy entrance, a lack of crevasses, a beautiful hike in and out and a nice mellow grade for a couple rusty skiers who spent the whole summer walking.

Andrews Glacier and Tarn, Rocky Mountain National Park

Since returning from the CDT, one thing we’ve struggled with most is simply not being outdoors 24 hours a day. walking in the sun, sleeping on the ground, and all the goodness that provides. We were excited to get into the mountains for an entire day of adventuring.

We entered the park with our freshly bought annual pass, enjoying the morning light as it turned the meadows of Moraine Park a golden hue. The elk are converging in this place now, sheltered from the mountain winds and exposure. As is often the case in the Colorado Front Range, it’s been a windy autumn, so we had to pack accordingly:

A nice morning with hardly any other humans. Bear Lake, Rocky Mountain National Park.

Shoes were a dilemma for me. On our last night in Glacier National Park before driving home, I was cooking pasta for the group, and accidentally poured scalding boiling water all over my big toe in the pitch darkness. It instantly swelled up and blistered, and soon after popped and turned raw. For a few nights I couldn’t really sleep with anything less than four Advil in my system. It’s been a painful mishap, but since the trail was over and this is supposed to be a relatively easy month, it came at the best time possible.

One accommodation I’ve had to make to the injury is cutting open the toe of my left shoe to avoid aggravating it. Since the shoes I was wearing already had 750 miles on them and were well worn, it was a small sacrifice to make. But having an open toe was going to be less than ideal climbing onto the snowy, windswept Continental Divide. I packed a plastic bag, to be put on between the sock and shoe to keep snow and moisture out when we got above timberline. It’s a trick we picked up on the trail.

On this day, we wanted to do a loop and get on the divide. The Continental Divide, our home this year, has been calling to us. We decided to loop around Bear Lake and begin the long steady climb up to Flattop Mountain. Flattop is a nice smooth, fast trail that climbs about 2,500 feet in three miles. Usually it’s overrun with folks, but on this very blustery day in mid-October, we hardly encountered a soul.

Elaine makes her way up firm snow on the Flattop Mountain Trail. The constant wind packs it down to a near solid texture.

The trail up Flattop winds gradually through the forest, switchbacking through lodgepole pines. While the wind howled overhead, the trees dampened the blast, making a peaceful sighing noise as we climbed. Alert squirrels, busy shoring up their winter food stock, scolded us, as has been the case for the last five months. An agitated squirrel is a peaceful, calming sound for us now.

As the altitude rose, the trees shrank. At 11,000 feet the forest gave way to gnarled branches and webs of krummholz, those hardy “trees” that spend much of the year getting blasted by the wind and cold. Above this, it’s all ground vegetation, rock, ice and tundra – trees simply can’t live here.

These above-timberline areas are shrinking worldwide, thanks to a warming planet. The forest is encroaching. Slowly but steadily, we are losing alpine tundra. Eventually forest will crowd out alpine meadows, but that won’t simply result in a few less wildflowers. Sheep, goats, deer and elk depend on that tundra for summer feeding. As the forest grows to cover everything, there will be less genetic biodiversity, and with that some species will not survive.

It doesn’t stop there. Flowers that now only live on the top of peaks will run out of space. The small mountain pika, whose “eeekkk” cry defines the Rocky Mountain timberline, rely on those plants to live. Pika are literally being driven up and off the mountain. There was talk of putting them on the Endangered Species List, but the Bush administration exempted greenhouse gasses from control under the Endangered Species Act. That’s not a happenstance event – climate sensitive species are regularly turned down for protection.*

Back on the divide! Otis Peak in the foreground, Longs Peak in the background.

These things get lost in the politicized world of economic growth versus environmentalism, but they are of real consequence. It goes beyond pika and plants. In nature everything effects everything else. Scarce food means some animals die. Another animal, another ecosystem that relies on that source also dies. How far does it go? Right to humans ourselves?

It’s important to ramble in the mountains, but also to look and observe, to take off the headphones and heart rate monitor and see what is actually going on. To go regularly, to feel and see the change, to report back and raise a ruckus. So…we go to timberline to ski, but also to observe and learn.

As we climbed above timberline the wind grew brisk. Dirt gave way to snow drifts, hard and slick from the constant pounding of the wind. This concrete snow is our first layer, or base, and will be here until June. It was time to put the plastic bag inside my open shoe and layer up. Up we went until soon we were on top of Flattop Mountain, a wide open, appropriately named “peak” on the top of the Continental Divide. Even better, we were back on the Continental Divide Trail.

Stoked to be back on the Continental Divide Trail. Tyndall Glacier and Hallett Peak in the background.

Spirits went from good to ecstatic. I realized it’s been some time since I have seen my wife smile that big. We were finally home again, the place we’ve lived for the past half-year. The wind blew strong and we walked south on the CDT. You don’t get anything material for hiking the CDT, but you do get the feeling that you got the Continental Divide melded into your soul, like you know it and somehow possess it. That means much more than a medal or certificate.

The mountains surprise sometimes. As we headed south, the wind died down, defying logic for the place we were. It was good to be on the tundra again, maneuvering over talus and testing the firmness of snow drifts for sure footing. One thing I have noticed after hiking 3,000 miles – there is no tentativeness in step or hesitation on uneven terrain. There is a comfort and balance walking that has been honed during the past months.

Hallett and Otis Peak loomed on our left. This is the very heart of glaciers in Colorado. Steep and dramatic Tyndall Glacier came first. We peered over its edge into another realm, icy and ancient. Onward south, and a warning sign said “Chaos Glacier is steep and can have large crevasses. Use Extreme Caution. Not Advised.” And then, up a talus field, along the ridgeline and we had reached the snowy banks of our destination, Andrews Glacier.

Looking off the divide onto Andrews Glacier.

The glacier itself is wedged into a notch between two mountains on the eastern side of the divide. At this latitude, barely above the 40° parallel, wind is the driving force behind these glaciers. Snow on the upper reaches of the western side of the divide gets scoured and blows just over the edge to the eastern side. That’s why in this area at least, the eastern side of the mountains is usually more dramatic and glacier carved than the western side. Because of that wind, snow depths accumulate dramatically more in some places. I’ve seen this in effect – two inches of snow can pile into a foot where the wind deposits it just right.

Andrews offers nice easy access to a moderate route for early season turns. I’ve skied it for about ten years now – it’s something of an annual ritual – and it’s a very enjoyable, relatively safe excursion. Access this year was easy, as early season snow covered the usually steep edges of the glacier. It was simply a matter of popping ski boots on the tundra and gliding right onto the glacier.

It’s possible to tell the health of a glacier based on the snow line. Underneath the new season’s snowfall is something called a “dry glacier.” Dry glaciers are essentially very compressed snow and ice. They have a different look – they are much more grey and often have sediment in them. Dry glaciers can actually be quite safe to travel on with the right equipment because you can see what is going on – crevasses are fully exposed so one one won’t accidentally walk in.

“Wet glaciers” have snow covering the ice. This snow has not yet fully consolidated into ice form. On big glaciers with crevasses one has to exercise extreme caution because crevasses are hidden by the fresh snow. Sometimes those bridges are enough to hold a climber, and sometimes they are not. Back in 2008 on a NOLS mountaineering course in the Waddington Range in British Columbia we got a foot of snow one night in August. The next day was torturous travel, the person on the front of the rope essentially stepping into a crevasse every twenty steps or so, as the entire area was hidden under the new snow. The folks back on the rope holding the lead definitely had to be attentive on that day.

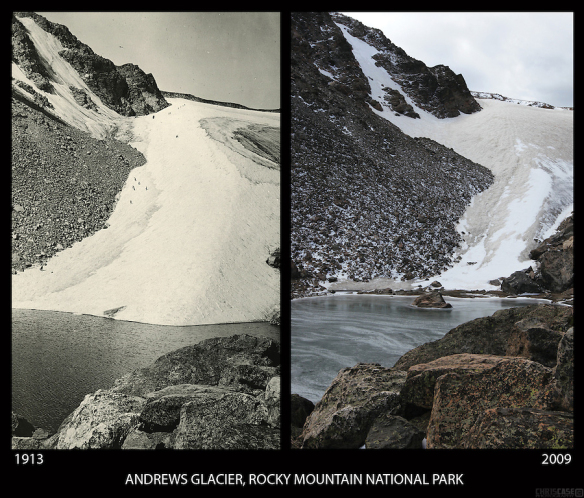

Glaciers accumulate snow for most of the year, but that window is getting smaller as the planet warms up. September storms are moving to October and June melt is being pushed to May. That leaves less time for the glacier to accumulate and more time for it to melt. Glaciologists usually take samples of glaciers at the end of the season, usually in early September, to see what the overall yearly effect is. A general rule of thumb is if the glacier is more than 50% “wet” at the end of the season, it’s growing and doing well. If it is more than 50% “dry,” the glacier is shrinking. Comparing the images below, it’s easy to see the difference. *

Like almost all mountain glaciers, Andrews Glacier has shrunk significantly from 1913 to 2009. Dry glacier is the browning colored ice. Wet glacier is white.

This year we arrived after peak melt off. Early season snows and wind has dropped a few new inches on the glacier surface, leaving it a glorious white color, and allowing us to temporarily forget that this glacier is dying. Crevasses are not really an issue on Andrews Glacier. It doesn’t have enough mass and is not moving enough to create massive fissures, and will be retired from glacier status once it stops moving altogether. That’s the difference between a snowfield and a glacier. Glaciers move, carve the earth and deposit sediment from the upper accumulation zone to the lower reaches of the ice. Snowfields, while providing valuable habitat and moisture. essentially just sit there. Their days of carving the landscape are done until the next ice age.

We were happy to see the new snow. Skiing on dry glaciers is not particularly fun. The surface is rough, often full of massive sun-cups. On this day, however, the new snow had compacted to create a firm surface, perfect for making some almost resort-like turns. As we sat on top of the glacier transitioning from trail running shoes to ski boots, enjoying a snack, a raven flew past, rising and falling in the currents before darting across a mountain face, in search of prey or maybe just for the sheer joy of it.

Elaine feeling small as she makes the first turns of the season on Andrews Glacier.

The skiing itself was actually quite good, great even for mid-October. We picked the line with the smoothest snow and enjoyed setting our edges to make some turns. We are both very rusty, as we have not made a legitimate ski turn in three months. While we did send kid’s skis to ourselves in Wyoming and Montana to keep our seven year streak of skiing at least one day every month alive, it wasn’t really making turns. It was more shuffling and surviving. By the time we reached the lower flanks of Andrews, balance and agility came back and we were actually skiing half-way decently.

Conditions were firm and fast – kind of like most days at the resort. Finding my balance and rhythm on Andrews Glacier.

The run steepens a bit on the bottom and the snow had accumulated nicely on the north side of the glacier. We enjoyed some softer turns right down to the small lake at the bottom, already frozen over by the autumn cold. The world is warming, but this place is still one of the harshest climates around – that’s why there is a glacier here in the first place.

Glaciers tend to melt from the bottom up, and this is where I have personally noticed the most difference in Andrews Glacier. When I first started skiing it back in 2008, the glacier extended right into the lake. Now, ten years later, it’s backed off 50 to 60 feet from the lake’s edge, revealing instead talus and rock. That’s just the vertical downsizing. It’s also shrinking on the sides, as well as in total depth and mass. Andrews Glacier is dying. We were fortunate though on this day. The new snow had covered much of the talus so we were able to ski right to lake’s edge before transitioning back to running shoes.

Elaine enjoys buttery turns on the lower flanks of Andrews Glacier.

Something we miss most about the trail is how the massive mountains and big sky country makes you feel small and inconsequential. Humans are no match to time transcending things like glaciers, ice ages, erosion and volcanic uplift. And then there are the threats – rock fall, cliff edges, icy lakes, lightning, river crossings and avalanches. There are many things that could kill us in a heartbeat. Living with that, seeing how nature works (not always kind) makes you realize that while humans may think ourselves incredibly brilliant and important, we’re very, very small and fragile.

And yet, for Elaine and I, that isn’t something we fear. In an odd sense, we enjoy it, because it makes us realize that all this stuff we worry about, the minutia of every day life, in the end means almost nothing. You learn to relax, to worry less, to just shut off the mind and be. And in that mountain cirque, surrounded by glaciers and massive cliff walls and higher mountains, we set down our packs, ate lunch, and just enjoyed being. Enjoyed being quiet, listening to the wind, the clatter of the pika, the small creek meandering down the meadow.

A very nice day up on Andrew’s Glacier and the Continental Divide. This was our 85th straight month skiing together.

We’re an odd species. So fragile yet dangerous at the same time. We can change the local forest or stream, but beyond that we can impact the climate of the entire planet. It seems like an odd choice for nature to have made. Why would something be allowed to survive that is so destructive to the natural balance? And as a species, why would we insist on destroying our natural home? That makes no sense, and that feels to me like a suicidal path to take.

I know this. I like glaciers. I like big snows and bitter cold. I want them around for my lifetime and for generations to come. To give all that up without a big fight would be a mistake.

* The Melting World, A Journey Across America’s Vanishing Glaciers. Christopher White.

* The Melting World, A Journey Across America’s Vanishing Glaciers. Christopher White.