I remember one afternoon near the end of undergrad, my father asked me why I’d never taken any German literature as part of my degree. It was a fair question; by the end of high school I was fairly fluent in German, especially after a summer spent on the Rhein with a friend’s family (his father’s first and only rule: no English to be spoken). Later, during my PhD, one of my most memorable jobs was as a freelance translator—I had a successful stint rendering medical reports into clinical English for an insurance company (though I felt poorly prepared for concepts like “tick borne encephalitis” or “mild diffuse intermittent pain”). The answer I gave my father was simple: German literature just didn’t do it for me. I apologise in advance to all germanophones–the feeling was not a reasoned response to wide reading, and in retrospect, clearly a sign of my own limited judgment. Even so, since that conversation, although I read more widely in translation than in English, I’ve barely touched a German writer (with the exception of Robert Walser).

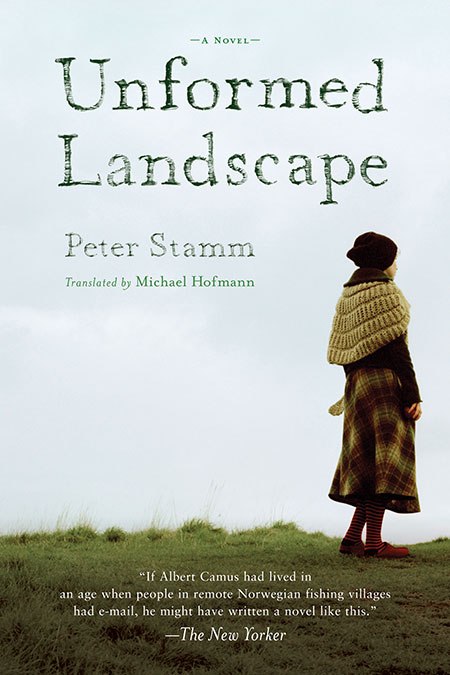

All that changed when someone recommended Peter Stamm to me. I was sceptical of this Swiss author to begin with—a clear sign of my lingering prejudice—but when I finally got round to reading one of his shorter novels, Unformed Landscape, I was completely captivated by his laconic prose. Building fiction out of simple, direct sentences with sparse descriptive detail, Stamm nonetheless manages to completely immerse the reader in haunting landscapes and the quiet desperation of unfulfilling lives.

Unformed Landscape follows a half-Sami woman as she leaves her tiny town in Finnmark (in the far north of Norway) on a trip to Paris that becomes the most understated journey of self-discovery I have read. I would thoroughly recommend it–like all of Stamm’s work that I have read, it’s power comes from the impulsive, compulsive actions of his characters. They may have thoughts, but often their actions seem disconnected from their conscious brain, pushing them towards a looming threat that fails to eventuate.

The same sense of compulsion and bathos is even clearer in On a Day Like This, which traces the unravelling life of a Swiss-born German teacher living in Paris. The protagonist has more wry self-awareness than Katherine in Unformed Landscape (he actually reminded me of a close friend and his desultory time spent teaching in France), but his actions are no less erratic than hers. Driven by an unrevealed diagnosis to leave his job and apartment, Andreas becomes overtaken by memories of a teenage love, and Stamm builds something beautiful out of this desperate self-destruction. That description doesn’t ring quite true, though, because like Unformed Landscape the prose in On a Day Like This is precise and painstakingly plain. For me, this was a quiet revelation: the quality that made me feel put off by so much German writing (what I thought of as a workmanlike, mechanical functionality) is transformed by Stamm into something transcendent. I felt a bit like Mary McCarthy, when she describes falling in love with the simple clarity of Caesar’s prose style.

This intense simplicity finds its best expression in Stamm’s short fiction. I have just finished the 2012 collection We’re Flying, and it is one of the most intense and engaging pieces of writing I have read this year. A personal favourite was “Summer Kind,” a story where the narrator (an academic specialising in Gorki’s women) finds the mountain hotel he had been recommended is being run by a squatter. Clearly there is more wry humour here than in some of his novels, but the short form also intensifies his characters’ disappointment with their lives. Few writers are brave enough, or clear sighted enough, to show people as unfulfilled as Stamm does—but these stories work so well in part because he seems to have found the alchemy for balancing this desperation with a kind of dignity. Perhaps the best endorsement I can give Stamm’s work is that he has made me interested in the German language again, by showing how the starkly functional can also be transporting.

Advertisements Share this: