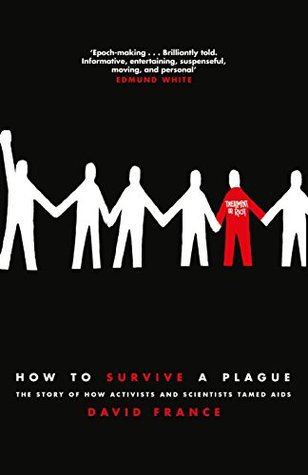

Spanning from the summer of 1981, when the New York Times first broke the story about a rare cancer observed in homosexuals, to 1996, when protease inhibitors came onto the market and offered HIV sufferers a new lease on life, How to Survive a Plague is a comprehensive history of the AIDS crisis. Especially in its early chapters, it reads like a fascinating medical mystery – though we already know the answers, the book skillfully captures the ignorance and terror that reigned for so many years as people sought to understand what Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID, the original name for AIDS) was and how it was transmitted.

As a journalist and a gay man, David France was right in the thick of the crisis when he moved to Manhattan in 1981. He lost friends and lovers to AIDS, and had his own health scares, too – once, on assignment in war-torn Central America, he developed what he thought was a Kaposi’s sarcoma lesion but turned out to be a sign of amoebic infection.

As a journalist and a gay man, David France was right in the thick of the crisis when he moved to Manhattan in 1981. He lost friends and lovers to AIDS, and had his own health scares, too – once, on assignment in war-torn Central America, he developed what he thought was a Kaposi’s sarcoma lesion but turned out to be a sign of amoebic infection.

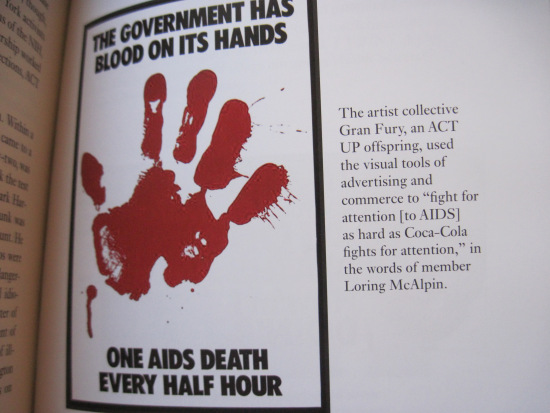

Throughout the 1980s the number of HIV cases roughly doubled each year; media coverage was intense but often alarmist. Undertakers refused to deal with AIDS victims, and Jerry Falwell and his ilk spoke of a gay conspiracy taking over America. Far too slowly, research advanced to cope with the crisis. France gives details of the medical trials and presidential commissions that kept AIDS at the forefront of the national conscience, generally thanks to patient advocacy groups like ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and PWA (People with AIDS – more proactive terminology than victims or patients).

The book reminds me most of Sheri Fink’s Five Days in Memorial, another social history with a vast scope and a large cast of characters; here there are about 25 doctors, researchers and activists, many of them based in New York City, who keep recurring. For instance, there’s Joe Sonnabend, an infectious diseases expert who specialized in treating gay men for venereal diseases; Larry Kramer, who wrote an angry novel about fellow homosexuals yet tried to lead the response; and Richard Berkowitz, a former sex worker who co-wrote How to Have Sex in an Epidemic, a safe sex guide that encouraged a surge in condom use.

I rather underestimated the reading load the Wellcome shortlist would create for me; I ended up getting bogged down in this 500+-page book’s level of detail and only succeeded in skimming it. I think that for someone without a personal stake in the story of AIDS, watching the 2012 documentary film of the same title that spawned the book would be an easier way to absorb copious information and keep track of all the individuals and organizations involved.

Nonetheless, I can certainly affirm the importance of a landmark book like this one. When I surveyed critical opinion on it for Bookmarks magazine, I noticed many comparisons to Randy Shilts’s 1987 And the Band Played On, but while that book was written in medias res and deliberately vilified a French-Canadian flight attendant named Gaëtan Dugas who was linked with multiple AIDS cases in North America, How to Survive a Plague benefits from two decades of hindsight and reflects a mixture of journalistic objectivity and personal grief.

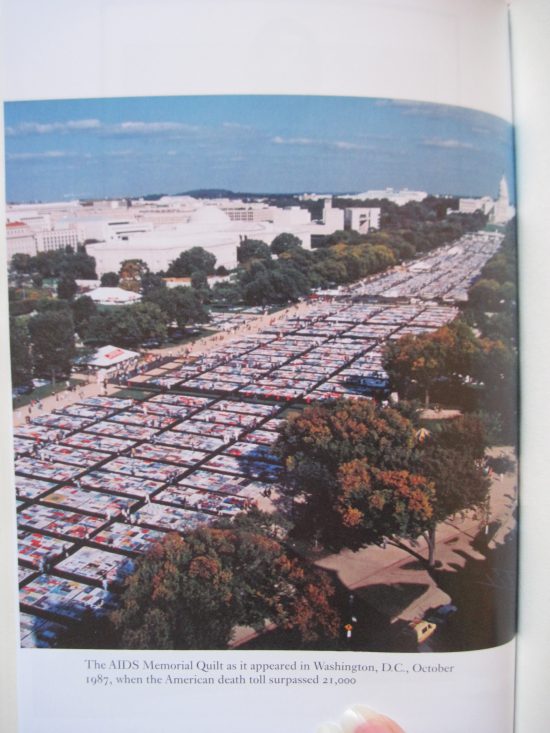

The AIDS memorial quilt on display in Washington, DC.

The AIDS memorial quilt on display in Washington, DC.

It’s sobering to remember the scale of the AIDS epidemic: 100,000 Americans had died of it by 1991. As one HIV-positive ACT UP activist cried out to Bill Clinton, then a Democratic candidate, at a campaign event, “Bill, we’re dying of neglect!” France’s book really brings home how traumatic these years were for a whole country, but especially for homosexuals. He describes the relief of knowing that effective medical treatment was finally in the pipeline, but also the lingering effects of shame, bitterness, and fear.

Nobody left those years uncorrupted by what they’d witnessed, not only the mass deaths—100,000 lost in New York City alone, snatched from tightly drawn social circles—but also the foul truths that a microscopic virus had revealed about American culture: politicians who welcomed the plague as proof of God’s will, doctors who refused the victims medical care, clergymen and often even parents themselves who withheld all but a shiver of grief. Such betrayal would be impossible to forget in the subsequent years.

My rating:

My gut feeling: France has written a definitive history of the AIDS crisis in the United States. It’s a cautionary tale that must not be forgotten. While not among my personal favorites from the shortlist, it would be a worthy winner.

More reviews:

Paul’s at Nudge

Clare’s at A Little Blog of Books

Stay tuned for our shadow panel winner, which I will announce here tomorrow morning! Advertisements Share this:- Doorstopper of the Month