In my previous post, I wrote about proper names versus descriptions and how that issue is inscribed in the world of Batman from the character’s very first appearance in 1939.

Another theme that will loom large in my books, and that also is prefigured in the very first appearance of Batman, is the use and nature of quotation marks. Some of my memes will derive their humor (or ‘humor’) from how quotation marks interact with punctuation, and from words appearing both within and without quotation marks in the same sentence. Quotation marks are one of the primary means we have in English (and in many other languages) for referring to language itself. At least on the face of it, they provide a simple and standard way by which we can refer to any bit of language – simply take that bit of language and put quotation marks around it. We will thus establish instances of the schema:

[QUOTATION-MARKED EXPRESSION] refers to [BIT OF LANGUAGE].

(Things get complicated pretty quickly if we try to give instances of this schema. [You can skip this parenthesis if you like.] The right-hand side of the schema calls for a bit of language. But I can’t just put a bit of language there; I have to refer to it, and thus enclose it in quotation marks. And if I want to refer to the quotation marked-expression on the left-hand side that refers to that bit of language, I need a quotation-marked expression to refer to it! So I need to put the quotoation-marked expression in another set of quotation marks. Thus, an instance of the schema will end up looking not like this:

“David Kaplan” refers to David Kaplan,

which states a relation between a bit of language and a person (David Kaplan), but like this:

” “David Kaplan” ” refers to “David Kaplan”,

which states a relation between a quotation-marked expression and a name (a name of David Kaplan). Got it?)

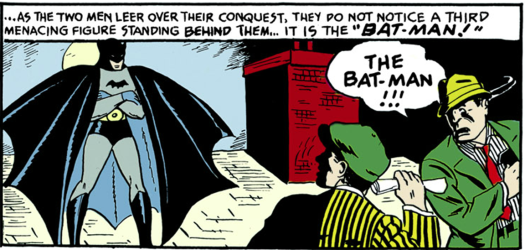

In any case, going back to Batman (or the Bat-Man), in the first Batman story ever, in Batman’s first ever appearance other than on the cover of the comic, we see this:

What leaps out at me when I see this is that in the text in the caption, the expression “Bat-Man” appears in quotation marks while in the speech bubble, it does not. This pattern – quotation marks in the narratorial captions and none in the speech bubbles – seems to persist throughout the story (though I have not been able to see all of it, and don’t know how the usage develops in subsequent stories). There is just one lapse in the first few pages of this story where the caption text omits the quotation marks. So, quotation marks are central in the world of Batman, right from the very start.

Whatever the quotation marks are doing in the caption text, they do not seem to be performing the function I described above of allowing us to refer to bits of language. They seem more akin to scare quotes. Scare quotes serve to create some distance between a speaker/writer and a term she uses, sometimes for ironic effect but sometimes just to draw attention to the term for some reason. This would make sense of the caption/speech bubble distinction in the first Batman story. In the captions, the narratorial voice is distancing itself from the term, letting us know that this strange usage is not its own, but rather reflects what the characters in the comic say. When the characters speak, they use the term unselfconsciously and without any distance. It would make an interesting study, along with the study envisaged in my previous post of the transition from the descriptive phrase “the Bat-Man” to the proper name “Batman,” to trace the vicissitudes of the quotation marks in Batman comics. My guess would be that fairly quickly, as the character of Batman became known, the narratorial voice no longer felt a need to use the term “Batman” in a distancing way and the quotation marks disappeared. But that is pure speculation.

In his book The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture, Glen Weldon, in his discussion of the 1960s Batman TV show, brings up the topic of camp and refers us to Susan Sontag’s famous essay “Notes on ‘Camp’,” in section 10 of which she writes: “Camp sees everything in quotation marks.” Sontag’s pronouncement is striking but not very easy to understand. At first, I thought that the quotation marks she is referring to are scare quotes, not quotation marks functioning as I described at the beginning of this post, as devices to generate expressions to refer to bits of language. She goes on to say: “It’s not a lamp, but a ‘lamp’; not a woman, but a ‘woman.’ To perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role. It is the farthest extension, in sensibility, of the metaphor of life as theater.” But I struggled to connect the life-as-theater metaphor with the use of scare quotes. Is the idea that in camp, a character who turns on a lamp in fact distances herself from it? That doesn’t really seem to capture what is distinctive about camp. And scare quotes require a contrast between a speaker who uses them, and some other point of view or language user – but Sontag’s “it’s not a lamp but a ‘lamp'” doesn’t really explain who the speaker would be and whose the contrasting perspective.

As I thought about it more, though, I had another idea. Something I will talk about elsewhere in my book is the idea of a Lagadonian language. The term, and the idea, come from Swift’s book Gulliver’s Travels. In the city of Lagado, sages are working on a scheme to save people’s lungs from talking-induced corrosion. Their expedient is to let everything be its own name. (Among other things, this has the consequence that one can only discourse about things one can carry about one’s person!) Predictably, contemporary philosophers have been intrigued by the idea. You can read what Swift says, and find some references to philosophical uses of the idea, here.

What, then, if we take Sontag’s suggestion as referring to quotation marks in their function of allowing us to refer to bits of language, but in the context of a Lagadonian language? A lamp is the name of a lamp; a woman the name of a woman. By putting everything in quotation marks, camp draws attention to the way in which its action is a representation of itself. All life becomes a representation of life. Since in theater, we represent a woman turning on a lamp by having a woman turn on a lamp, the way in which life is its own representation is as theater. Indeed, any utterance in a Lagadonian language is necessarily a piece of theatrical representation.

In the spirit of Sontag’s connection of camp with theater as representation, here are some theatrical representations of my Batman slapping Robin memes. I think they qualify as camp:

Advertisements Share this: