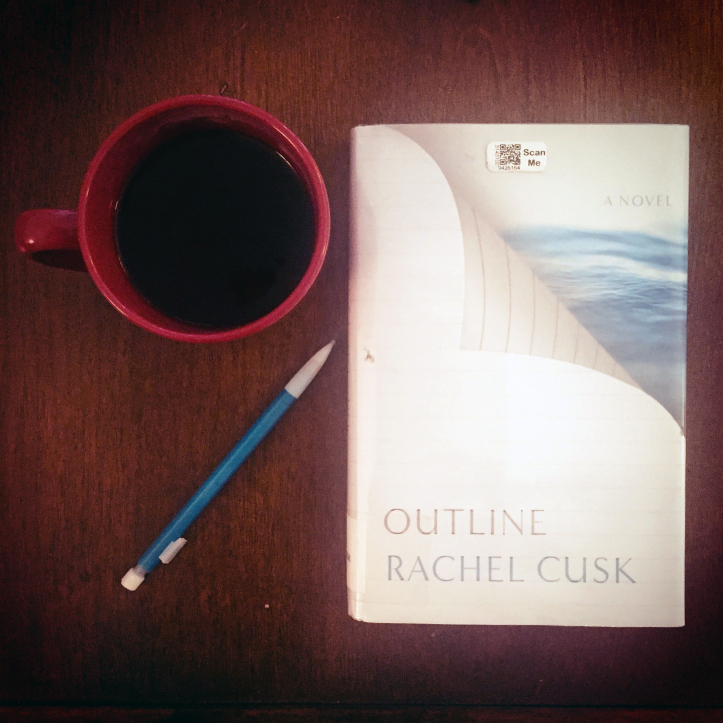

Inspired by a New Yorker profile, I recently read Outline, the first novel in a trilogy by Rachel Cusk. The story, narrated by a recently divorced woman and practically nameless woman, is conveyed through the detailed re-telling of 10 separate interactions had over the course of a very hot summer spent teaching writing in Greece. During these interactions, characters speak at length about themselves while the narrator depicts herself as saying little. However, through the details shared about the others and through occasional interior responses to those details, a subtle portrait of the narrator emerges. She is a woman whose sense of self has been set adrift. She longs for an original pre-wife/motherhood self. But she finds that original self she hoped might return following divorce, no longer exists and she no longer knows who she is. We see her grief at the loss of self through the details she chooses to share about the others, most of whom also have had their first identities weakened or modified by various life circumstances.

My Reading Kit

My Reading Kit

The novel’s pervasive lack of characters with strong self-identities suggests a question Cusk wishes the reader to consider: Is there such a thing as a concrete, unchanging self? Might identity be nothing but a figment of imagination tied entirely to time and place? Or – might it be solely tied to our interactions with others – a possibility reflected in the unique and widely praised structure of the novel, in which our understanding of the narrator is fully dependent on the characters with whom she interacts.

One thing seems clear. Memory plays a role in the conception of self. Nearly all characters use the past to define themselves in some way. The narrator’s grief is nothing if not a disappointment at memory’s inability to actualize in the present. But memory is as unpredictable as it is unreliable. As such, Cusk’s characters encourage a bit of meditation on the nature of memory and its relationship to our sense of self. To start, can we have as a clear a sense of self in the present as we do in our memories of the past? Or, given the unreliable nature of memory, did this earlier idea of self ever really exist? Why do we work so hard to define ourselves? Is it the nature of a complex human brain to do so? If the complexity of the the human mind requires us to seek a definable self, and if those definitions rest on an error ridden foundation of context and memory bound to collapse in one of life’s many storms, what is the benefit of defining self? Would it be better to simply resist identity altogether and to exist according to the needs of the moment and time? Are we even capable of such resistance? Or, are we only capable of making new equally error-laden memory to override and replace the identities we think we have lost? These are all questions, Cusk’s narrator seems ponder.

As I too ponder these questions I consider the significance of the title. Why Outline? In writing, an outline is a basic structure to guide the creation of a more fleshed out text. The narrator’s divorce and the crisis of self it creates has has stripped the flesh from her structure. To clarify, the memory of self she had used to give flair to structure of her humanity has shown its limitations in defining her presently. Her experience over the course of the novel shows her tentatively beginning to add new detail to that outline – to deepen and re-imagine the self within this new context. In the narrator, Cusk may be working to define grief precisely as periods when the memory of self and its role in our present is disrupted. In part, we all live in the past. Grief springs us painfully to the present – to our basic humanity – and the limitations of our outlines – and forces us to re-imagine the possibilities of self.

This re-imagination seems to be the chief concern of Transit, the next novel in Cusk’s trilogy, which has Faye back in England and working to construct a new foundation for her post-divorce self. How will she further develop her outline? What existential questions will the process raise? How will the texts structure reflect its existential concerns? I look forward to finding out.

Share this: