“Once you say yes, you can’t say no!”

“Once you say yes, you can’t say no!”

Steven has given his consent to something rather strange. His baby brother, Theo, is just ten days old, but everyone is discussing the fact that he has been born with a condition, and that he might shortly die. As doctors debate Theo’s health, a low atmosphere hangs over the house: Steven’s little sister, Nicola, is oblivious to it, but Steven himself is anxious by nature and soaks up his parents’ sadness and fear. Then, the night after a wasp sting, he begins dreaming of a white cave: indistinct, angelic figures in white who reassure him they know best. They can ‘fix’ the baby – all Steven has to do is say ‘yes’.

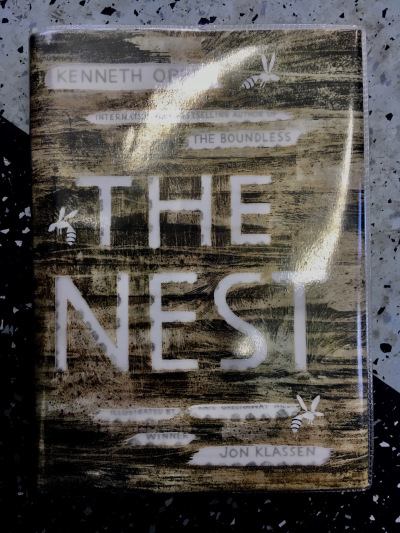

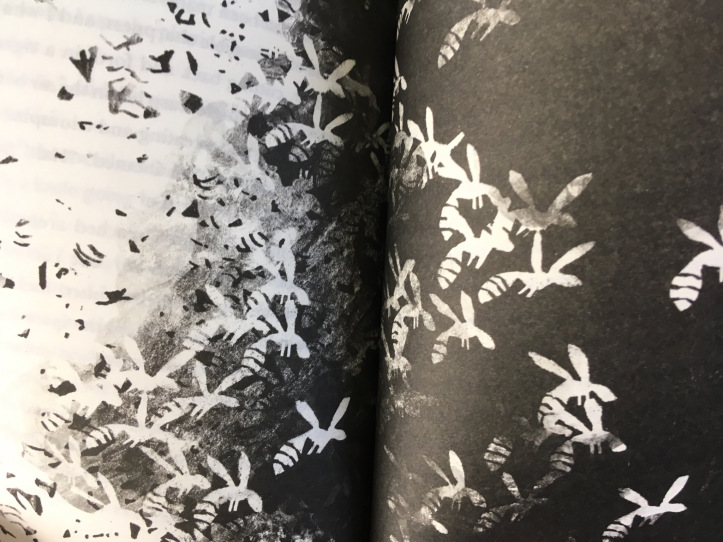

Like the hornet, the insect pervading The Nest (2016) in every sense, Kenneth Oppel’s novel packs a surprising wallop for its unassuming size. It’s only 244 pages of quite large print, and, in fact, the hardcover edition is roughly the proportions of that newish genre of illustrated books for newly confident readers (I’m thinking of Reeve & McIntyre’s books, or Chris Riddell’s, among others). What with the illustrations at chapter headings and throughout, I do wonder whether this book might not be too easily offered to a younger reader, not quite ready for the dark areas Oppel visits. Perhaps the publishers are confident that readers will recognise something in the style of Jon Klassen’s pictures (which are dark, blurry and oblique as half-remembered dreams) that signals this is not a book to be treated lightly.

(Interesting that in two consecutive weeks, I’ve ended up talking about two books for older readers that heavily feature illustration. Perhaps I’m just naïve about the capacity of children to handle sterner stuff. I’d love to hear more on this from parents, teachers and librarians.)

(Interesting that in two consecutive weeks, I’ve ended up talking about two books for older readers that heavily feature illustration. Perhaps I’m just naïve about the capacity of children to handle sterner stuff. I’d love to hear more on this from parents, teachers and librarians.)

Ostensibly, the brevity and simplicity of the plot resemble a fable, folk tale or fairy tale. Indeed, before starting the book, I was already thinking of Lynne Reid Banks’ The Fairy Rebel (1985). The protagonist of Banks’ book is an adult woman, Jan, and like The Nest, the plot concerns a baby: Jan can’t have children, but through the work of Tiki (and expressly against the rules), a child is born. I remember my own sense of maturity, reading that novel as a child (of perhaps nine or ten), and the thrillingly unexpected visitation of the Queen of the Fairies, who comes for the child, in the company of a lot of flying insects. I haven’t read the story for years, but I clearly recall bees oozing out of Jan’s toothpaste tube, and swarming through the house.

With that book in mind, and with a particular love of fairy narratives (derived mostly from Katharine Briggs’ wonderful The Fairies in Tradition and Literature , 1967), I brought a particular interpretation of the ethereal beings that visit Steven to strike a bargain. Fairies, after all, though they have no particular stable, unified identity in British legend or elsewhere, are often involved in bargains and ideas of right behaviour. People who try to renege on a deal with a fairy, often end up blinded or in some way barred from great rewards. Fairies, too, often lead children astray in some way – or steal babies away and leave changelings in their place.

Oppel’s novel, though, presents the mysterious wasp-like creatures with enough ambiguity, and attention to their animal character, to transcend my reading alone. At the outset of the novel, Steven asks them if they are angels, and they are happy to be called that. The use of their waspishness, their secret natural history, even if they are not ‘real’ wasps, is clever for the sense of connection and identification it conjures. Caves of bed-covers for frightened children, and houses themselves, are referred to incidentally by characters as ‘nests’. The novel is full of Steven’s anxiety over the capacity to become ‘abnormal’, even for the natural to become unnatural, which is there from birth (“I imagine you didn’t look very appetizing when you were just conceived and starting to grow in your mother’s womb,” the queen tells him, at one point) or in his own, embarrassing anxiety and fearfulness: “My parents thought I was abnormal, I was pretty sure. They said I wasn’t, but you don’t get sent to a therapist if you’re normal.”

Oppel’s novel, though, presents the mysterious wasp-like creatures with enough ambiguity, and attention to their animal character, to transcend my reading alone. At the outset of the novel, Steven asks them if they are angels, and they are happy to be called that. The use of their waspishness, their secret natural history, even if they are not ‘real’ wasps, is clever for the sense of connection and identification it conjures. Caves of bed-covers for frightened children, and houses themselves, are referred to incidentally by characters as ‘nests’. The novel is full of Steven’s anxiety over the capacity to become ‘abnormal’, even for the natural to become unnatural, which is there from birth (“I imagine you didn’t look very appetizing when you were just conceived and starting to grow in your mother’s womb,” the queen tells him, at one point) or in his own, embarrassing anxiety and fearfulness: “My parents thought I was abnormal, I was pretty sure. They said I wasn’t, but you don’t get sent to a therapist if you’re normal.”

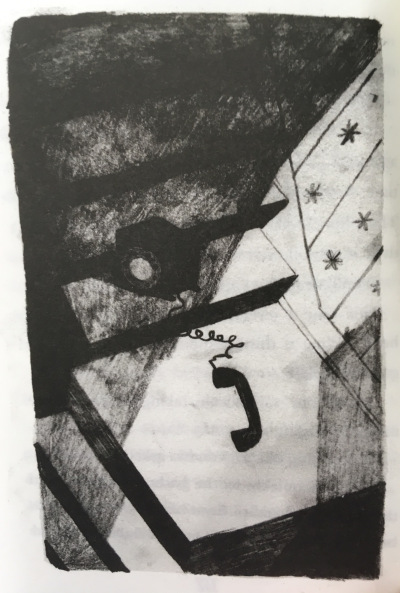

For much of the narrative, the possibility is left open for the reader that the whole bargain is one a bad dream; that is, indeed, why Steven agrees to the ‘fixing’ of Theo. It can’t be real – can it? It’s established that Steven has a history of anxiety, and when he discusses his ‘angel dreams’ with a doctor, it’s not a new experience. Part The Nest’s disturbing quality is the way it denies a therapy narrative: when Steven confesses his fears and dreams to parents and doctors, it has no cathartic effect whatsoever. Increasingly, the dreadful truth behind (or rather, inside) the nest on the wall of his house, and of the sickle mysteriously left on their doorstep, and of the ‘nobody’ on the other end of a phone-line, encroach further on the real, waking, shared world.

For a small book, Oppel’s narrative moves relatively slowly and carefully. Small details emerge and gather as the book unfurls, and only in the penultimate chapter do fearful things move from the implicit to the explicit. In my experience of contemporary children’s literature, there is a tendency, particularly in fantastic literature, toward narratives of friends, gangs and teams. The extreme subjectivity, isolation and interiority of The Nest, and its ambiguities, combine in what I would call a rewarding, literary text, one that calls on the power of the reader (I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend this to an adult ). I find it interesting that such qualities come hand-in-hand with something approaching the horror genre (certain aspects of this text would not be surprising in the work of Stephen King) which, in the world of adult reading, is more associated with throwaway entertainment. I’m excited that a writer like Kenneth Oppel is bringing such nuance, strangeness and wildness to contemporary children’s literature and I look forward to reading more of his work.

The Nest is published by David Fickling Books. Please consider buying your copy from your favourite independent bookshop (or order it through your local library).

Advertisements Share this: