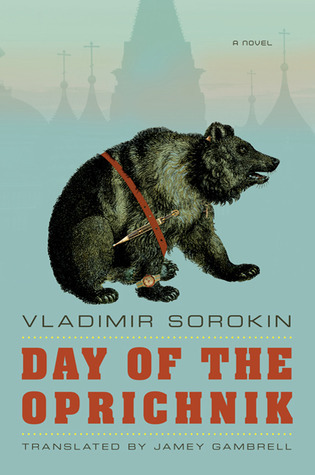

Russia Reviewed’s Post-Apocalyptic/Dystopia summer series concludes with a review of Vladimir Sorokin’s Day of the Oprichnik.

Vladimir Sorokin appears to be one of those rare authors whose novels elicit a lively reaction not only among conscientious critics, but also among laymen. The court seems split: some, including novelists Gary Shteyngart and Keith Gessen (quoted on my copy of DotO’s dust jacket), praise Sorokin as a genius, while others denounce his work as – among other things – second-rate porn. You either love his books or hate them; middle ground is hard to find. And after reading Day of the Oprichnik, my first Sorokin book, I can see why readers are so polarized: Oprichnik offers striking themes and clever commentary, but buries them under mediocre prose, vulgarity, and disturbing shock value.

As befitting a dystopian novel, Sorokin offers a very bleak vision of Russia’s future: by 2028, Russia has inexplicably imploded, sealing itself off from the outside world with a Great Wall to help purify the Motherland. Inside “Holy Rus” thrives a quasi-Draconian society of “Russian Orthodox” people ruled over by a czar. Yet people also receive news from bubbles, do drugs in the form of tiny fish penetrating the bloodstream, and use advanced technology imported from China. Wrap your head around that.

Oprichnik covers one day in the life of Andrei Komiaga, a member of the czar’s trusted and feared oprichnina. The oprichnina oversee arrests and executions to cleanse Russia of traitors and criminals who break the czar’s laws (one notable law forbids swearing, for some reason). Over the course of this 200-page novel, we see Andrei and his vile lot murder, rape, extort, and commit arson in the name of Country interests, always minding their own pockets and the need to pay the higher-ups. The oprichniki censor plays and rape women whom they have just made widows; they attend lavish parties and take hallucinogenic drugs. They leave a trail of destruction in their wake, accountable only to the czar.

It’s not a pretty picture, but Oprichnik, like Tolstaya’s The Slynx, is packed with interesting critique. While obviously meant to mock the current Russian government, the book’s themes are also more universally applicable. Chief among them is a warning about what happens when society falls blindly to a ruler or religion. But I’ve heard similar messages before – in Fahrenheit-451 and It Can’t Happen Here, for example. Luckily there are some more subtle ones: how easy it is to use the mask of nationalism and religion to pursue ignoble ends; how we can work at our jobs and gloss over the harm we may be doing; how the trappings of power sometimes corrupt more than power itself.

Sorokin couples these themes with a dose of black comedy. One can point to scenes of a clairvoyant burning the “useless” Russian classics (p. 114) or an oprichnik cursing at someone while reprimanding them for cursing. Or one can point to the opening sequence: Komiaga is woken by his movilov (mobile phone) and is catered head to toe by his servants, who each greet him with the same phrase: “The best of health to you, Andrei Danilovich!” He prays to St. Boniface, St. George the Dragonslayer, Saint Nikola, and the Optina Elders while his servants dress him in medieval garb and hand him a dagger in a scabbard. Andrei then chooses the particular breed of dog head that will be mounted on his mercedov (Mercedes) in order to intimidate all he passes. Okay, humor is subjective, but one can at least see the cleverness in Sorokin’s flavor of it. Even Oprichnik’s overall concept – an archaic monarchy persisting in a technologically advanced society with brutal consequences – is one that piques my interest.

It is unfortunate, then, that in order to reach the clever bits, one must dig through a lot of muck. Oprichnik’s prose is flat and uninspired. The narrative is ill-paced and chock-full of irrelevant information – for example, the details of fictitious trade agreements which have no bearing on the plot. And it’s hard to believe – even given the vast resources at the oprichnina’s disposal – that all these events happened in a single day.

It’s time to address the jaundiced, mutilated, slightly smelly elephant in the room: the shock value. Yeah, I don’t like it. Those of you who have read Oprichnik before know what’s coming. But I’m going straight to this example in order to demonstrate how deliberate vulgarity can actually harm a story. Within the last 50 pages of the book, Andrei takes part in a same-sex oprichnina bathhouse group orgy. I barely caught the commentary – about moral corruption or how homoeroticism can be housed and flourish in a homophobic/nationalist society – because, well, human centipede of sodomy. (And I’m in no way a squeamish reader!) The same goes for the multiple rape scenes (at least one of which is gang rape): readers are more likely to remember the graphic imagery than the message at heart (if in fact there is one). Go ahead with your dystopia and your dark themes, but I should not feel unclean after reading your book.

In conclusion, Vladimir Sorokin’s Day of the Oprichnik is…well, it’s definitely an acquired taste. There’s amusement to be had if one sticks around long enough and works past the mediocre and sometimes obscene aspects of its execution. At the same time, it is completely understandable if after reading this, you decide Sorokin is not for you. Bottom line: the Great Divide over Sorokin is justified.

★ ★

Day of the Oprichnik by Vladimir Sorokin. Translated from the Russian by Jamey Gambrell. Pub. 2011 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Hardcover, 191 pages. ISBN13: 9780374134754.