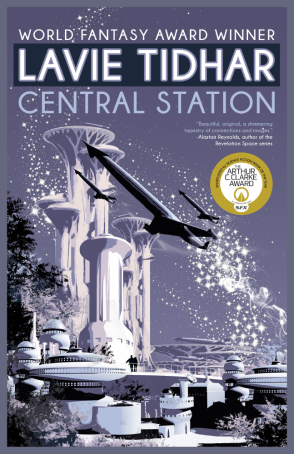

This extraordinary, big-hearted novel looks at life in and around the titular space port in Tel Aviv from a range of perspectives. Past, present and future blend in the sensuously-rendered ‘real’ world and the virtual environs of a post-Internet system called the Conversation.

The book references many other science fiction writers, from the phrasing and mosaic structure of works by Cordwainer Smith and Clifford D Simak to the depiction of easy access to extraordinary technology and the resulting borderless, inter-racial societies explored by the cyberpunks. However, ‘Central Station’ is not some noirish futuristic thriller; it deals with a society built over old wounds and conflicts that are not resolved so much as rendered unimportant by the sheer passage of ordinary years. It is as if Lavie Tidhar has made something wholly new out of fragments of other science fiction, in the same way as the denizens of his novel have made an unexpectedly cohesive society out of bits and pieces of old inventions and religions.

Two ideas underlie the narrative: one is the famous John Lennon quotation about life being what happens when you’re planning your main event; the other is about the inexorability of change. Indeed, the book combines these two themes so effortlessly it is easy to overlook how sublime the storytelling is.

Being science fiction of course, what is ordinary to the characters is extraordinary to us: a maker of gods who could be some kind of artist or, literally, a maker of gods; a haunted data-vampire girl and her lover, who is deemed an invalid because he cannot access the Conversation; a woman who runs a little bar whose adopted son may be a vat-produced messiah and the woman’s erstwhile lover, who may have been the boy’s creator.

It is not so much the originality of these ideas that is striking so much as the characters’ practical, stoic and humane responses to them. The boy might be a messiah, but he is still a boy. The data vampire may be part of a larger mystery, but she is still a vulnerable young woman; the god artist may be uncanny, but he appreciates the friendship of an old builder dissolving in memories he cannot control and a rag and bone man who is probably immortal.

Very few novels convey the feeling of dense and busy time, compacted over centuries, quite as well as this one. There are stories within stories and a medley of languages from Hebrew to the pidgin English of immigrants who came to Tel Aviv as workers and stayed for generations. The result is that rare thing: an actual science fictional language, as multifaceted conceptually as it is phonetically.

This achievement would be considerable on its own. That it is filtered through obstinate, loving, confused human beings and their post-human counterparts (the lovely old robot priest R. Brother Patch-It, who is also a part-time moyen; the old ‘robotnik’ cyborg soldiers who can’t get parts anymore; the eerily mischievous digital Others) in a way that is not only recognisable but compelling makes ‘Central Station’ one of my favourite books of the year.

Buy ‘Central Station’

Lavie’s website

Share this: