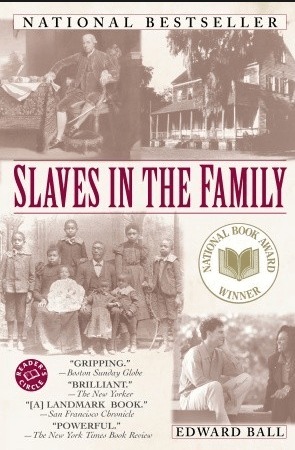

A few years ago I was perusing the shelves of a local bookshop in Pawleys Island, South Carolina and a title caught my eye. I pulled it from the shelf and was confronted by the intriguing title Slaves in the Family. I flipped the book over to read the summary on the back and was further intrigued by the photo of the author, Edward Ball. He was a white man. I made my way to the counter and bought the book, but I didn’t actually pick it up to read it until months later.

When I finally did, I was completely swept away. I’ve always been fascinated by the history of the lowcountry in South Carolina. It goes back to when I was a kid and my family first visited this area. We took a boat ride up the Waccamaw, Black, and Pee Dee Rivers in Georgetown County and I was transfixed. After all these years, the rice fields are still there, with their flood gates and ditches. I tried to image how it would have been to be stuck in those fields. The boiling heat, mosquitoes, snakes, and God only knows what else. But there was absolutely no way I could know what a lifetime of this felt like.

Flood gate for the rice fields (photo by author)

Flood gate for the rice fields (photo by author)

Dormant rice field (photo by author)

Dormant rice field (photo by author)

The dormant rice fields up and down the rivers of the lowcountry are one of the few landmarks that can actually be seen from space. They stretch as far as the human eye can see in some places and were the foundation of great wealth in South Carolina for hundreds of years. The family at the center of Slaves in the Family is just one of the families who made their fortune from Carolina Gold.

The Ball family is one of the oldest families in South Carolina. The author of Slaves in the Family is Edward Ball, a living descendant of this family. He estimates that there are over 100K descendants of slaves owned by his family, living today. And with his book, he set out to find some of them.

It all began with this man – Elias Ball.

Elias Ball

Elias Ball

When Elias stepped off a boat from England in the late 17th century, he was a young man who had arrived to collect an inheritance. That inheritance came in the form of Comingtee Plantation, 25 miles up river from Charleston where the Cooper River split and made a natural “T”. At that time, this area was still very much Indian territory and wilderness. Elias’ uncle, Captain John Coming, had arrived in South Carolina in about 1668 and within a few years had secured a land grant of 186 acres. Upon his death, the land passed to his wife and upon her death it was split between two men, with Elias Ball receiving half.

Gates of Comingtee Plantation today (courtesy of Tom Taylor @ randomconnections.com)

Gates of Comingtee Plantation today (courtesy of Tom Taylor @ randomconnections.com)

Comingtee was just the beginning. By the time Elias’ descendant, Edward Ball, began pouring over the ten thousand page family archive in preparation for writing Slaves in the Family, he would find meticulous documentation from a total of 25 rice plantations that Elias and his descendants had owned up and down the Cooper River. These included Limerick, Ballsdam, Kensington, and Quinby.

Limerick Plantation (photo courtesy of The Charleston Museum Archives)

Limerick Plantation (photo courtesy of The Charleston Museum Archives)

Quinby Plantation, Circa 1921 © Harriette Kershaw Leiding

Quinby Plantation, Circa 1921 © Harriette Kershaw Leiding

Ballsdam Plantation (photo courtesy of The Charleston Museum Archives) – house built 1835

Ballsdam Plantation (photo courtesy of The Charleston Museum Archives) – house built 1835

The magic of Slaves in the Family is that Ball uses this family archive to track down living descendants of some of the 4K slaves his family once owned. He contacts each one, unsure of the reaction he will receive, but compelled to do it nonetheless. He was rewarded by an amazing verbal history, passed from generation to generation, about life during slavery. When combined with what Ball knew of his own family, the result is a complex history that blends both the story of slave and master into a picture of life on a rice plantation. It also redefines the notion of family in the antebellum South.

During this journey, Ball develops new friendships. Friendships like with Thomas Martin whose grandfather was born at Limerick Plantation, a place Thomas had never been until he met Edward Ball. They took the trip together, both trying to understand the past. The main house is now gone, replaced by railroad tracks, but the majestic avenue of oaks that once led to the house, remains.

Site where the main house of Limerick Plantation once sat (where the tracks are in foreground), looking back down the alley of oaks to the gate – photo courtesy of the South Carolina Department of Archives and HistoryBall describes this experience:

Site where the main house of Limerick Plantation once sat (where the tracks are in foreground), looking back down the alley of oaks to the gate – photo courtesy of the South Carolina Department of Archives and HistoryBall describes this experience:

Mr. Martin was quiet and watchful as we strolled beneath the oaks. Until this moment he had shown few emotions about the past. On the subject of slavery, he seemed to prefer a respectful, almost intellectual detachment.

‘This is hallowed ground,’ Mr. Martin said suddenly. ‘I feel like I’m walking in the footsteps of Jesus….Some of my friends would resent this, our being here together,’ said Mr. Martin, looking around carefully. ‘Some of my in-laws, in fact, resent it.’

For the first time, Mr. Martin allowed himself to ruminate. ‘The letters you showed me from my grandfather to your great-grandfather – I don’t recognize his treatment during slavery as, say, the kind of slavery that television would have shown. There is nothing about his having been beaten. I have to wonder what kind of people the Ball family were.’

Descendants of slave and owner, walking together – trying to understand.

‘When I was in my twenties, I had a different impression about slavery,’ Mr. Martin continued. ‘I was not forgiving. I was unable to do what I wanted, and I blamed it on slavery, or rather, on white people. My philosophy has changed since I was a young man. Terrible things happened to our ancestors, but we’ve got to make something of ourselves.’

I asked Mr. Martin whether he thought there was anger among black people.

‘Yes. How many people would do what we are doing now? The first thing they would ask is, ‘How much am I going to get out of it?’ I don’t think that we will ever get anywhere, blacks and whites, until we’re able to sit down together.’

This is the true lesson of Ball’s book – understanding and forgiveness. With this book, Edward Ball faces his family’s slave-owning past – he puts it out there for all the world to see. Factual, not apologetic. Those slave descendants he meets do something just as brave – they talk with Ball about it, sharing stories.

Slavery in the South happened and cannot be erased, regardless of how many statues and flags are pulled down. We as a society have to come to terms with it as part of our history, acknowledge it, and then move on from it.

After all…we share it.

Cover photo courtesy of Tom Taylor @ randomconnections.com.

Share this: